OPERATION PIED PIPER

WWII was declared on September 1st 1939, and by the end of that month over 800,000 London school children had been evacuated to the countryside ahead of the expected German bombardment.

Planning for Operation Pied Piper, as it was known, began years earlier. The bombing casualties sustained during WWI had frightened the British government badly. Taking into account advances in technology, they were certain that should war break out with a remilitarized Germany, any bombing campaign would result in catastrophic loss of civilian life.

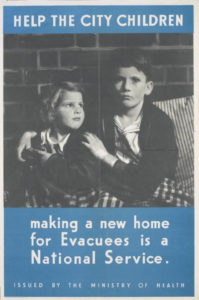

As war grew closer, the government divided the country into zones of “evacuation” “neutral” or “reception”, compiled lists of available housing, and began an all-out crusade to convince the public of the necessity of evacuation. Posters and pamphlets were used successfully to persuade parents that their children would be safest far from the inner cities, especially London. Teachers, local authorities, railway staff, and over 17,000 WVS (Womens’ Volunteer Service) volunteers were brought on board to assist with the planning and implementation.

To prepare for evacuation, parents were given a list of items each child needed to take with them which included a gas mask, sandwiches for the journey, and a small bag containing such essentials as a change of underclothes, pajamas, slippers, toothbrush, comb, washcloth, and a warm coat. Yardly Jones recalls preparing before his evacuation:

“We went down Wavertree Road and bought an enamel cup, a knife, fork, and spoon from a list we had. I guess we bought clothing as well, I don’t remember, but I do know I was a little upset since I knew we weren’t that well off and I knew my mother couldn’t afford to go out and buy these things.”

The day of departure, children assembled at their local school where labels were attached to their collars with name, home address, school, and destination. After tearful farewells, teachers and volunteers marched the children to the station where trains waited to take them to such far-flung destinations as Devon, Cornwall, and Wales. Teacher L.A.M. Brech recalls:

“All you could hear was the feet of the children and a kind of murmur because the children were too afraid to talk. Mothers weren’t allowed with us but they came along behind. When we got to the station we knew which platform to go to, the train was ready, we hadn’t the slightest idea where we were going and we put the children on the train and the gates closed behind us. The mothers pressed against the iron gates calling, ‘Goodbye darling.’ I never see those gates at Waterloo that I don’t get a lump in my throat.”

![]()

Upon arrival, billeting officers arranged for housing. In many instances, this meant nothing more than lining the children up against a wall and allowing families to choose as Beryl Hewitson recounts:

“I noticed boys of about 12 went very quickly—perhaps to help on the farm? Eventually only my friend Nancy and myself were left—two plain, straight-haired little girls wearing glasses, now rather tearful.”

And Irene Brownhill remembers her own arrival in the country:

“…next to us a little thin girl sobbing and very upset and wanting her mother. I put her in the middle of my sister and me and she stopped crying. The people coming around to choose kept saying they would take my sister and me but they did not want three girls only two…”

It was common for the young evacuees to have trouble adjusting to country life. Some had never seen a farm animal before or eaten a fresh vegetable. Others were bored by the lack of entertainments outside of the city. Jean Chartrand remembers two boys billeted with her relatives:

“…one boy had put the pail under the cow’s udders and was holding it there whilst the other boy was using the cow’s tail like a pump handle…”

Evacuee John Wills said his biggest shock was the fresh air: “Nearly knocked us off our feet.” Later he and a friend decided to return to London. “We walked home on the thumb with the odd lift. I much preferred to take my chances in the air raids.”

Host families could be equally surprised by the children they were housing. Because the majority of children came from the poorer sections of cities, there was an idea that they would be undisciplined and dirty. And while this was sometimes the case, more often than not their fears were founded on bias and preconceived notions.

“How I wish the prevalent view of evacuees could be changed. We were not all raised on a diet of fish and chips eaten from newspaper and many of us are quite familiar with the origins of milk. It was just as traumatic for a clean and fairly well educated child to find itself in a grubby semi-slum as vice versa,” Jean McCulloch explained.

By the end of 1939 when the expected bombing didn’t materialize, parents were quick to bring their children back home. And by January of 1940, nearly half of those children sent away in the first weeks had returned to their families. But these were to be short-term homecomings. When France fell in June 1940 and again in the fall of 1940 at the start of the London Blitz, additional evacuations were set in motion. And this time, children would not see their families again until the end of the war almost five years later.

The lasting effects of the evacuation ran the gamut. Some had idyllic experiences with caring families who maintained close ties long after the war ended like Michael Clark:

“We could not understand these strange people who for some reason we were sent to live with, but as the years have gone by I realize just what diamonds they were”

Others, like Gloria McNeill, homesick and unhappy, recall the forced separation and sometimes squalid and violent conditions these children found themselves in.

“Every time I hear Vera Lynn sing “Goodnight children everywhere’ I see a forlorn 11-year old curled up in a corner of a strange bedroom, hiding tears behind the pages of The Blue Fairy Book.”

Operation Pied Piper officially ended in 1946 bringing to a close one of the largest organized movements of civilian population during wartime and one of the most heartbreaking and inspiring chapters of British history.

Sources:

Dwight Jon Zimmerman. “Operation Pied Piper: The Evacuation of English Children During World War II.” www.DefenseMediaNetwork.com

Laura Clouting. “The Evacuated Children of the Second World War.” www.iwm.org.uk

“Primary History World War 2: Evacuation” www.bbc.uk

Ben Wicks. No Time to Wave Goodbye (Stoddart Publishing, 1988)

From the author of Secrets of Nanreath Hall comes this gripping, beautifully written historical fiction novel set during World War II—the unforgettable story of a young woman who must leave Singapore and forge a new life in England.

On the eve of Pearl Harbor, impetuous and overindulged, Lucy Stanhope, the granddaughter of an earl, is living a life of pampered luxury in Singapore until one reckless act will change her life forever.

Exiled to England to stay with an aunt she barely remembers, Lucy never dreamed that she would be one of the last people to escape Singapore before war engulfs the entire island, and that her parents would disappear in the devastating aftermath. Now grief stricken and all alone, she must cope with the realities of a grim, battle-weary England.

Then she meets Bill, a young evacuee sent to the country to escape the Blitz, and in a moment of weakness, Lucy agrees to help him find his mother in London. The unlikely runaways take off on a seemingly simple journey across the country, but her world becomes even more complicated when she is reunited with an invalided soldier she knew in Singapore.

Now Lucy will be forced to finally confront the choices she has made if she ever hopes to have the future she yearns for.

Author Bio:

Critically acclaimed author of historical and paranormal romance, Alix Rickloff’s family tree includes a knight who fought during the Wars of the Roses (his brass rubbing hangs in her dining room) and a soldier who sided with Charles I during the English Civil War (hence the family’s hasty emigration to America). With inspiration like that, what else could she do but start writing her own stories? She lives in Maryland in a house that’s seen its own share of history so when she’s not writing, she can usually be found trying to keep it from falling down.

Website: www.AlixRickloff.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/AlixRickloffAuthor

Twitter: www.Twitter.com/AlixRickloff

Pinterest: www.Pinterest.com/AlixRickloff

Intstagram: https://www.instagram.com/alix_rickloff

Buy This Book: http://bit.ly/2oM4Gy4