Born in Birmingham, needlewoman Mary Linwood moved to Leicester with her family when she was nine, where her mother opened a private boarding school for young ladies in Belgrave Gate, and where Mary herself became a schoolmistress and later headmistress. Mary worked her first needlework picture at the age of 13 and went on to produce a collection of 64 pictures, specialising in full size copies of old master paintings that were worked worked using a combination of irregular and sloping stitches to more closely resemble paint.

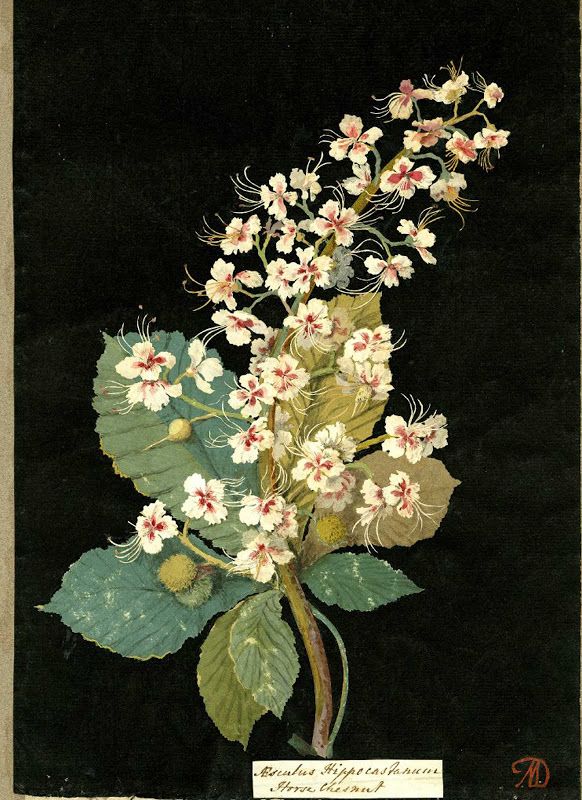

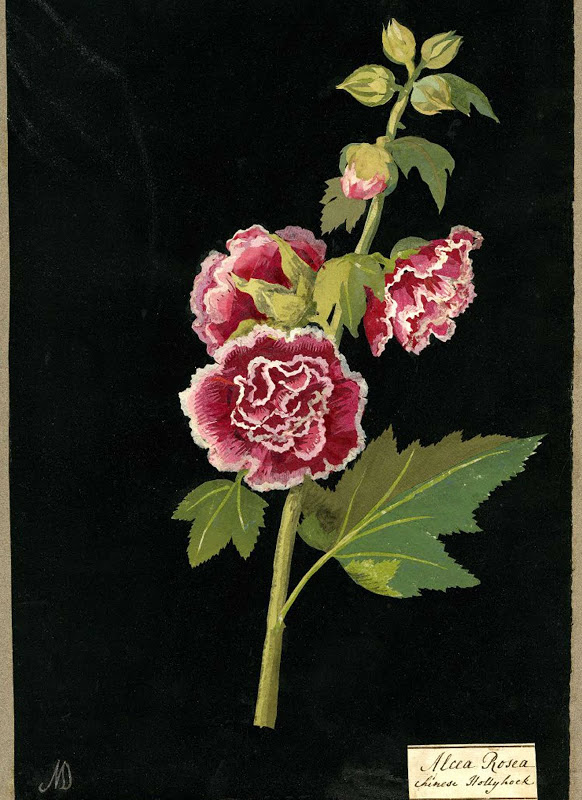

By the age of 31, Mary had attracted the notice of many, including the royal family and in particular that of especially Queen Charlotte, who had been such a champion of Mrs. Delany’s needlework. Mary moved to London and opened an exhibition of her work at The Panthenon, Oxford Street and in 1776 and 1778 her pictures were displayed at the exhibition of the Society of Artists. In 1785 she was summoned to court at Windsor by George III to show her work and according to the Morning Post there were ‘several pieces of needlework wrought in a style superior to anything of the kind yet attempted’ for which she received the Queen’s ‘highest encomiums.’ In the following year Mary sent examples of her work to the Society for the Encouragement of Arts and was awarded a medal. Word of her work spread and in 1783 the Empress Catherine of Russia accepted an example of her work, whilst the King of Poland was also numbered amongst her supporters.

In 1798 Mary began a series of exhibitions in n the Hanover Square Concert Rooms where she showed thirty nine copies of her work. In 1809, the collection moved into a permanent gallery at Savile House, Leicester Square, the former studio of Sir Joshua Reynolds, the property of the Earl of Aylesbury, where she held an exhibition of fifty-five ‘needle paintings.’ The exhibition remained opened until her death in 1845. She was a regular tourist attraction, mentioned in Curiosities of London and Mogg’s New Picture of London and Visitors’ Guide to its Sights in which the writer observed: “This beautiful style of needlework is the invention of a Leicestershire lady, and consists of fifty nine of the finest pictures in the English and foreign schools of art, possessing all the correct drawing, just colouring and light and shade of the original pictures from which they are taken; in a word, Miss Linwood’s exhibition is one of the most beautiful the metropolis can boast and should unquestionably be witnessed, as it deserves to be, by every admirer of art.”

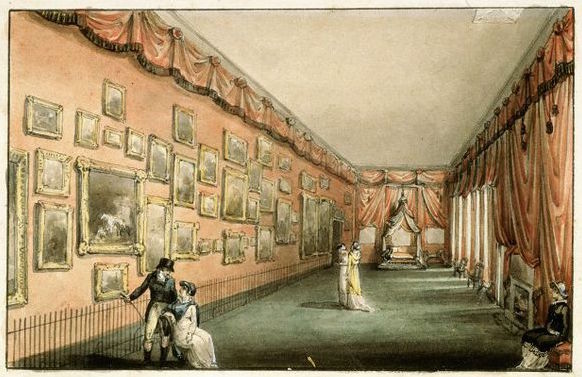

Mary’s exhibitions were the first to be lit by gas lighting to enable viewing late into the afternoon and she displayed each picture in a specially designed scene, her work being popular for nearly 50 years. Other exhibitions were held in Liverpool, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Belfast and Dublin. The pictures appear to have been cleverly set for picturesque effect. The principal room, a fine gallery, was hung with scarlet cloth, trimmed with gold; and at the end was a throne and canopy of satin and silver. A long dark passage led to a prison cell, in which was Northcote’s Lady Jane Grey Visited by the Abbot and Keeper of the Tower at Night; the scenic illusion being complete. Next was a cottage, with casement and hatch-door, and within it Gainsborough’s Cottage Children, standing by the fire, with chimney-piece and furniture complete. Near to this was a den, with lionesses; and further on, through a cavern aperture was a brilliant sea-view and picturesque shore. The large picture by Carlo Dolci had appropriated to it an entire room. The large saloons of Savile House were well adapted for these exhibition purposes, by insuring distance and effect.

A mention in Chambers’ Book of Days tells us that: The pictures were executed with fine crewels, dyed under Miss Linwood’s own superintendence, and worked on a thick tammy woven expressly for her use: they were entirely drawn and embroidered by herself, no background or other important parts being put in by a less skilful hand—the only assistance she received, if such it may be called, was in the threading of her needles.

And from Mogg’s New Picture of London and Visitor’s Guide to it Sights for 1844: Miss Linwood’s Exhibition of needlework is one of those which has not ceased to create an interest after its novelty had in a measure subsided, and is deserving, did the pages of this work permit, of a minute description. This beautiful style of picturesque needlework is the invention of a Leicestershire lady, and consists, at present of 59 copies of the finest pictures of the English and foreign schools of art, possessing all the correct drawing, just colouring, and light and shade, of the original pcitures from which they were taken; in a word, Miss Linwood’s exhibition is one of the most beautiful the metropolis can boast, and should unquestionably by witnessed, as it deserves to be, by every admirer of art.

The technique of this portrait is known as needlepainting, a type of embroidery, in which oils or other paintings were faithfully copied, with the brush strokes rendered by stitches worked in crewel wool. In 1808 Talleyrand introduced Mary to Napoleon, whose portrait she embroidered twice. He wanted her to take her exhibition to Paris, but was prevented by the outbreak of war between the two countries. Mary received the Freedom of Paris from him in 1825 for the portrait above.

In Music and Friends: or, Pleasant Recollections of a Dilettante, author William Gardiner writes:

“I have understood that Miss Linwood’s mode is analogous to that of a painter; she first sketches the outline, then the parts in detail, and brings out the whole of the design by degrees. I once saw her at work, accoutred as she was with pincushions all round her, stuck with needles, threaded with worsted of every colour, and after having touched the picture with a needle, instead of a brush, she would recede five or six paces back to view the effect. Leicester was a convenient place for dyeing her worsteds; still there were many colours she could not obtain: but being a woman of great genius, she set to work and dyed them herself. Miss Linwood’s skill was well known before she opened her exhibition in London, and it was a common practice for amateurs, in passing through Leicester, to stop and solicit a sight of her extraordinary performances.”

In 1844, during her annual visit to her Exhibition in London, Mary was taken ill and conveyed in an invalid carriage to Leicester, where her health rallied for a time, but a severe attack of influenza terminated her life in her ninetieth year. Mary had continued to exhibit her work until her death. Her last work, completed when she was 75 years of age, was The Judgement of Cain, which had taken her a decade to complete.

Upon her death, Mary’s collection of 100 pictures was offered to the British Museum who could not accommodate it. The work was auctioned at Mr. Christie’s auction rooms at Saville House on 23 April 1846 with the exception of a few. In her will she left her embroidered picture after Salvator Mundi by the seventeenth century Carlo Dolci to Queen Victoria. Mary had previously been offered three thousand guineas for this piece by the Marquis of Exeter of Burleigh House which she had refused. The whole collection fetched a disappointing £300. Her work is now in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Leicester Museum and Kew Palace. Mary Linwood was buried in St Margaret’s Church, Leicester.