by Victoria Hinshaw

Opening December 4, 2020, sixty-five of the greatest paintings in the Royal Collection will hang in the Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace until January, 2022. That gives us a year to get to London and binge on the Real Thing, usually seen only inside the Palace where the very nice but firm guards keep the crowd moving right along.

Recently, as part of the program to renovate the Palace and update its outmoded systems, the Picture Gallery was vacated and the contents put into storage, except for the masterpieces chosen to be exhibited for the next thirteen months while this portion of the building undergoes its share of the Reservicing Program, a ten-year period of repairs.

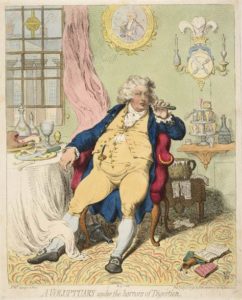

The Picture Gallery was added to the Palace in the 1820’s by George IV to house his art collection. Architect John Nash, the King’s favorite, designed the room, also used for state receptions. It has been updated several times most recently in the 1950’s.

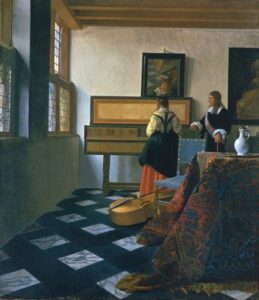

One of only 34 known Vermeer paintings, this canvas was acquired by George III in 1762. The relative simplicity of the scene concentrates the observer’s view on the figures and perhaps invites speculation on the relationship of the two. The delicacy of the light is a signature quality of Vermeer’s style and composition.

According to the description of the painting, “Claude was captivated by the effect of light in the landscape…we are transported directly into the scene.” This painting was probably acquired by Frederick, Prince of Wales, father of George III.

The description states “Reni dramatically conveys the foreboding of her passage from life to death…a shift from flesh and blood to cold marble.”

This painting was presented to Charles II in 1660 by the States of Holland and West Friesland upon his restoration to the throne. Titan stands as a giant of Italian painting for his realism, use of color and dramatic structure.

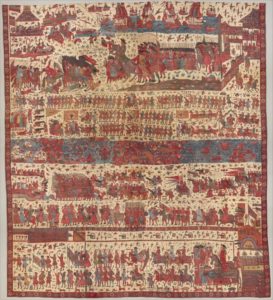

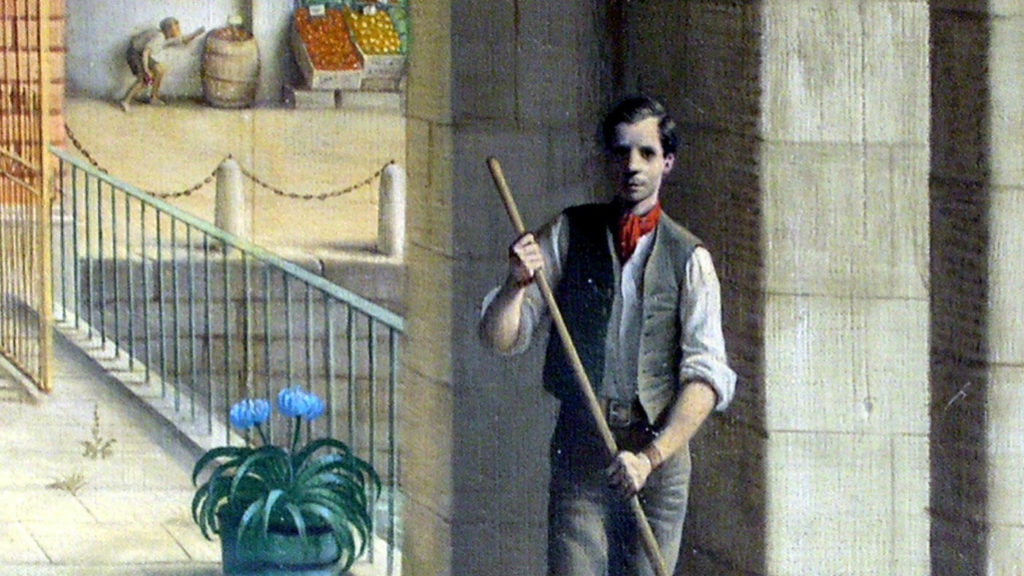

Canaletto is a favorite of the English, for both his Italian and his English scenes, all grand in scope but intricately detailed. George III acquired this painting in 1762 as part of the collection of Joseph Smith, British Consul in Venice. It portrays a celebration of the city’s Marriage with the Sea.

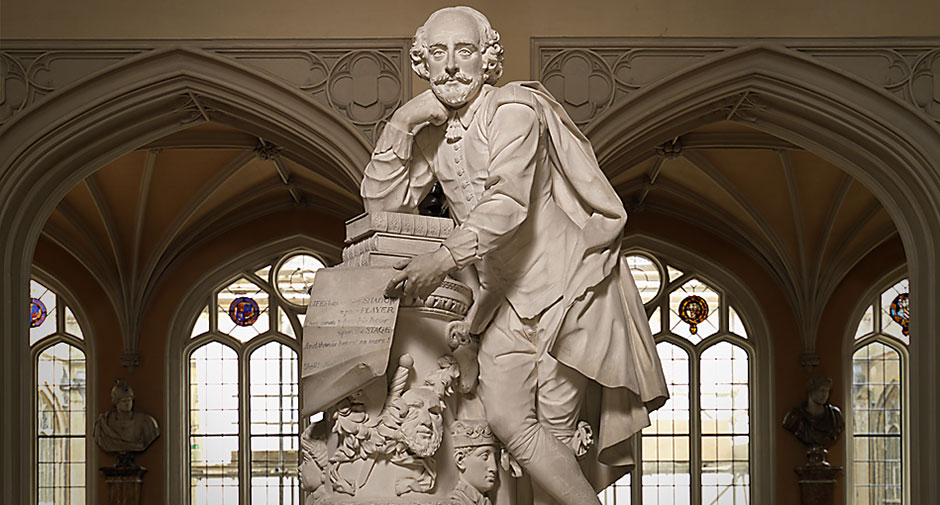

All these masterworks and more will be on view in the Queen’s Gallery long enough for us to get there, I hope! Once they are rehung inside the Palace Picture Gallery, more exhibitions from the Royal Collection will be mounted in the Queen’s Gallery. I have visited displays of Fabergé items, Leonardo drawings and artifacts, the Art and Love of Victoria and Albert, treasures from the courts of the first two Georges, and many more. All together they represent only a fraction of the total Royal Collection of 7,000 paintings, 500,000 prints, and 30,000 watercolors and drawings, plus sculptures, jewels, ceramics, photos, and manuscripts valued at well over $13 billion, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Hope I meet you there!