*CAVEAT FOR THIS SERIES OF POSTS*

This series of posts will endeavor to explain the different categories and names given to the various historical homes in England. There are specific criteria that define each type of home by the reasons for which it was built and the purpose it served in the lives of those who lived there. However, these designations are not written in stone (pun not really intended,) and they often changed over time based on additions made to them, renovations, architectural design alterations, and changes of ownership. So a manor house could become a stately home or a country house. A castle could become a manor house. A stately home could be called a castle—just ask Castle Howard. Add to that the names by which these homes were known—Chatsworth House, Lyme Park, Shugborough Hall and it can all be a bit confusing. The purpose of this series of posts is to give the reader a sort of guide from which to start when identifying the historic homes of England and perhaps to understand why and when they came to be. Names are important, especially to living, breathing beings, and these marvelous places are indeed very much alive.

What exactly is a palace?

The simplest and most often offered answer to this question is: A palace is the home of the king or queen. That answer isn’t wrong. However, there is more to the answer than that. A king or queen can and usually does live in a palace. A king or queen can also live in a castle. The presence of a king or queen does not turn a castle into a palace. To complicate the answer even further, a palace can be home to someone other than a king or queen. In English history at least, palaces have also been the homes of bishops, cardinals, and even powerful ministers in the government as well. Well drat, if that is the case, what distinguishes a palace from the other structures a monarch might call home?

The evolution of the word Palace.

The word castle came from the word castellum in Latin which designated a fort or tower built as a watchtower or for defense. Eventually castellum became chateau in French and finally became castle in English.

The word palace came from the word palatium in Latin which was the term the Romans gave to the hill in Roman cities where the wealthiest houses were. (Living on top of a hill in Roman cities was an advantage for a number of reasons. Do a little research on Roman sewers!) Palatium became palais in French which eventually became palace in English.

These terms were in use in England from the medieval era forward.

Of course there have been palaces in countries all over the world since long before they came into existence in England. Palace is most definitely not a western creation.

The earliest surviving palace is thought to be the Palace of Knossos on Crete which was built around 1950 BC, almost 4000 years ago.

What makes a palace a palace?

Hint: The Palace of Versailles contains 2300 rooms. Buckingham Palace contains nearly 800 rooms.

The following characteristics can be found in palaces.

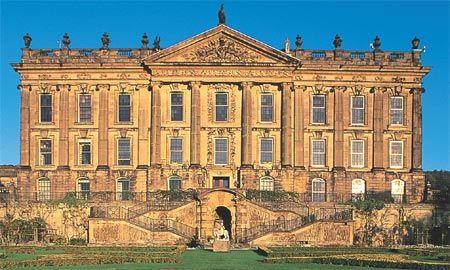

1. They feature elaborate architecture and decor.

2. The emphasis is on luxury and opulence.

3. They generally contain massive banquet halls.

4. They usually contain at least one ornate throne and throne room.

Buckingham Palace

5. They feature gilded, copious, and expensive table settings and other accessories.

6. The furnishings, linens, carpets, and drapes are usually of the finest and most expensive materials. Practicality? Optional. Time and effort to keep clean? Massive.

Holyrood Palace

7. There are usually large and numerous windows to allow in natural light. (And to show off the opulence more clearly.)

8. Gilt. Lots and lots of gilt. Pretty much gilt on anything that will sit still.

9. There are numerous large and ornate rooms designated for public entertaining.

Buckingham Palace

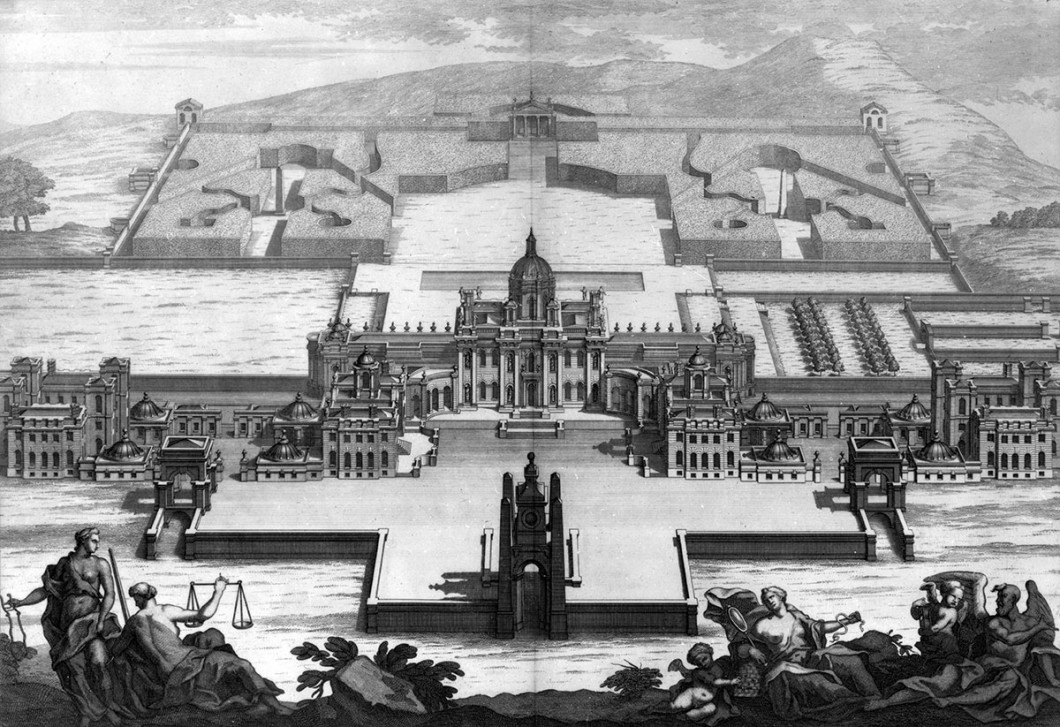

10. Most palaces are surrounded by expansive, beautiful, and creative gardens.

Defining a palace by its purpose.

It is in their purpose that we can separate the castles from the palaces. To refresh your memory on a castle’s purpose check out the previous post here:

https://numberonelondon.net/2024/04/what-makes-a-castle-a-castle/

Like a castle, a palace was built for a couple of very specific purposes.

1. No matter how lavish and expansive, a palace was built fundamentally as a home. Simply that – a home, not a base of defense.

2. Palaces were built to showcase the wealth, prestige, and power of the resident, be that resident a king, a bishop, or a government official.

3. Palaces were built to display the spoils of war. Kings and queens have been stealing the most expensive treasures from each other’s kingdoms and homes for centuries. Once these items were stolen one needed a place to display them. A palace served that purpose.

4. Palaces were built to house and show off the resident’s prized possessions which included artwork in the form of paintings, sculptures, and tapestries. Many of these were huge and therefore required large rooms with lots of floor-space and wall-space on which to display them.

As you can see a palace is a distinct entity unto itself. Just like the stately homes, manor houses, and castles in previous posts a palace is distinguished by its form and its function.

In the next post we will discuss what makes an English cottage so unique.