The Horrors of Baby Farming in Nineteenth Century England

Louisa Cornell

One question with which I am certain all authors are familiar is “How do you come up with story ideas?” Those of us who write receive this question from both readers and fellow writers. I will confess I never know when or where a story idea is going to leap out at me. Ideas can come from all sorts of places and some of those places are those I stumble across when I least expect it.

However, when one writes historical romance set in a specific era, like the Regency and early Victorian eras, research is certain to yield some fascinating and sometimes horrifying places from which to derive the basis of a story or even an entire series. Such was the case when Andrea K. Stein and I began to consider ideas for our third series together set in our own version of the Regency world.

Our first series – Steam, Lies, and Forbidden Desires came from the very real practice of pornographers in the era splitting a novel into four sections and selling each section as a separate novel.

Our second series – Five Pearls for the Earl came from a trip we took with Number One London Tours during which we visited Harewood House and a docent made a casual remark about why an earl’s coronet has five pearls.

Our current series – Bow Street’s Most Wanted – The Four Horsemen derived its root premise from a book I read in researching a class I taught on mental illness in the nineteenth century. Amelia Dyer Angel Maker: The Woman Who Murdered Babies for Money by Allison Rattle and Allison Vale. A fascinating read, but not for the faint of heart. Andrea and I considered what sort of children might survive such a horrific upbringing and what sort of men might they become. Thus, The Four Horsemen was born.

So what precisely was a baby farm?

In England in the 19th century unwed mothers and their infants were considered an affront to morality. They were spurned and ostracized both by the public and by relief and charitable institutions. For example in 1836 Muller’s Orphan Asylum in Bristol refused illegitimate children; they accepted only lawfully begotten orphans. The thought was that children conceived in sin would inherit their parents’ lack of moral character and would be a bad influence on legitimate children. Some orphanages accepted children no matter the circumstances of their birth. Others did not.

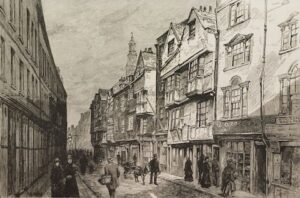

Young women who became pregnant out of wedlock were forced to leave home in disgrace and move somewhere they were not known. They were often scorned and abandoned by family and left with no resources. If they named the father of their child the parish would demand he pay for the support of the child, but those laws were difficult to enforce and little effort was made to do so.

There were few employment opportunities for single women in this era and the moment their pregnancy became noticeable they were dismissed. Once they gave birth their position became even less tenable as they had no one to tend their child whilst they worked. Thus, they resorted to baby farmers.

Baby farmers, the majority of whom were women, placed ads in newspapers that catered to working class women.

The ads look innocent enough. However, you will notice names are often not listed. Nor are actual specific addresses. No references are given nor offered. One ad suggested a fee of 15 shillings a week to keep an infant or a flat fee of 12 pounds to adopt. The weekly fee was not enough to keep a child, especially a sickly child, and for 12 pounds it was expected the mother would neither see her child again nor ask any questions. Infants under two months were the least likely to survive and the cheapest to bury.

Baby farmers were interested in only one thing. How much money could they squeeze out of the mother and/or father and for how long. A child’s life might hang on how long a mother might be strung along to keep paying. A single woman might not have 12 pounds, but she might be able to secure that amount from the father if he thought the child would disappear forever.

The majority of baby farmers solicited as many infants under the age of two months as they could. These children were the ones whose deaths would appear to be more natural. They would adopt many of these infants for the one time set fee and get rid of them at once. Those they kept were kept drugged on laudanum, paregoric, and other poisons. They were often given milk mixed with lime. The costs of burial was avoided by wrapping the infants’ naked bodies in newspapers and dumping them in dung heaps, deserted areas, or in the Thames.

Older children whose mothers did their best to pay the weekly fee and demanded to visit their children died longer, more torturous deaths. They died from slow starvation, being fed the bare minimum to keep them alive and lingering. Mothers worked day and night to support these children only to watch them waste away in the care of these supposed nurturing women.

Until 1872 there were no laws to govern baby farmers.

There were even some women who handed their children over to these baby farmers knowing full well that their child’s fate would be death. Unable to murder their own child they allowed the baby farmer to do so. A Mrs. Winsor was eventually arrested for the murder of a four month old infant whose body was found wrapped in newspaper on the side of the road in Torquay and traced back to her. She ran a lucrative business boarding infants for a few shillings a week or putting them away for a flat fee of 3 to 5 pounds. She was sent to prison for the crime.

A Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children was not founded until 1889. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was founded in 1824, 65 years before this.

The premise for our series is the age old author’s question, What if? What if four boys managed to survive the horrors of being raised on a baby farm? What sort of men would they become and what sort of lives would they lead?

Bow Street’s Most Wanted: The Four Horsemen

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DZV4QBLF/

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DZV4QBLF/