So you’ve committed a murder in Regency England. Now what? You could just leave the body there and run. But if you really want a chance at escaping the hangman’s noose you might want to dispose of the body. Let’s look at some possibilities.

STEP ONE: BODY DISPOSAL

Louisa Cornell

Body disposal during the Regency era was just as varied and contained just as many problems for both the murderer and the person dedicated to solving the murder as it does today. The advantage for the person set to solve the murder during the Regency was the lack of a constant stream of television shows instructing a murderer on how to dispose of a body. The majority of murder victims during the Regency were found where the murder actually occurred with no attempt made to hide or otherwise manipulate the body to get rid of evidence. That does not mean, however, that some murderers during this era did not come up with some rather unique ways to dispose of a body.

Some things to know about Regency Era crime investigation

(1) Once a murder victim was discovered, no matter where the body might be, there was a good chance the body would be moved, covered, or otherwise tampered with before law enforcement and / or the coroner arrived. Wounds might be bound. Clothing might even be removed.

(2) Should the body be found at a place of business, there was little to no chance the business would close until the body was removed. Business was business and the added cache of a murder victim lying about brought in more customers. Regency era people were above all realists.

(3) Depending on where the body was found and how long it took for the coroner to arrive with instructions, the location might become a tourist attraction with some enterprising soul selling tickets to view the body. As a result, items could be stolen or sold from the body before anyone had the chance to collect them as evidence. And the crime scene would be destroyed as well. Yes, especially in large cities like London or Edinburgh this could happen in a matter of minutes.

(4) Should a body be found other than in the victim’s home there is the possibility the body might be carried home by friends and family. Often this meant the body was stripped, bathed, bound and redressed before the coroner and law enforcement arrived. This did not happen often, but it did happen. This was more likely to happen in rural locations.

(5) Often a body that was hidden in some way made things easier for the coroner and law enforcement. A body that was hidden was last touched by the murderer, not a cast of thousands.

(6) However hidden bodies presented an investigator with its own problems. There were no tests to ascertain time of death. Wounds were often obliterated by the process of disposal and decomposition. Identification was more difficult, but not impossible, although there were no such things as dental records per se.

Water Disposal

Water disposal of murder victims was quite common during the Regency era. In the modern age water disposal is used to destroy evidence and in the hope the body might never resurface. In the Regency era, the idea of water destroying evidence didn’t really come into play in the average murder. However, it would be foolish to assume there were not murderers smart enough to know that water might help.

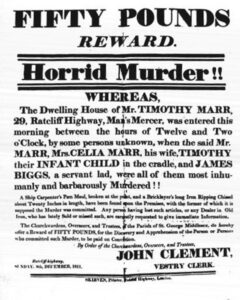

The Thames was notorious for the number of bodies that showed up floating in its waters. Riverside and dockside murder victims were often discovered in the Thames. Unwanted babies often ended in the Thames as well. Most of these murder victims came under the jurisdiction of the Thames River Police (established 1798.) Their normal duties involved stopping thievery from ships and in the transfer of goods from ships to the docks. They covered a large area, and if a body was found in the river and it was closer to their offices and jurisdiction they would investigate. More about them when we discuss who investigates a murder.

Bodies were also disposed of in rivers outside of London, as well as lakes and ponds as well. If a body was found in a body of water, the investigator would be safe to assume the murder had taken place either in the body of water or nearby. Transporting a body a long distance away in order to dispose of it was not an easy thing to do. Whether by horse or some sort of carriage or cart, the idea of spending time with the body of someone one had killed held little appeal for a variety of reasons—superstitions, in most communities a stranger would be noticed, worse in most communities everyone knew everyone, unless a person knew to weigh a body down there was no guarantee the body would sink before the murderer risked being caught nearby.

Bodies might also be disposed of in a well or cistern. Of course, if the well or cistern were one in use by a family, a community, or a business a body would foul the water and might be discovered all the more quickly. Good for the investigator. Bad for the murderer. No fun for the people who used the well for water either.

Some things unique to water disposal during the Regency Era

(1) A murder victim pulled from a body of water might be considered a victim of accidental drowning. Even with obvious wounds, depending on the body of water, the coroner and coroner’s jury might decide a murder is simply a drowning.

(2) This would be more likely in a rural setting than in a larger city. By the Regency era most of the physicians who practiced in the cities and / or kept up with the latest medical treatises knew how to ascertain if a victim was dead before they went into the water. Even in a rural setting where there was a competent physician families might object to the test to discover if their loved one had drowned as it involved dissecting the body at least enough to remove the lungs and float them in water. If they floated the person was dead when they went into the water and likely ended up in the water after they were murdered. If they sank, they were full of water which indicated a person was alive when they went into the water. Then the coroner and coroner’s jury had only to decide if the drowning was an accident or murder.

(3) Water disposal could erase a great deal of evidence from a body. However, the method of putting the body into the water might provide evidence of its own. People seldom considered that weighing a body down with items from their home, their farm, or a location associated with them might lead the authorities back to them.

(4) Any detritus associated with a specific body of water found on a suspect’s person or in a suspect’s home might lead the authorities back to them.

(5) Very few anatomists were able to distinguish between possible murder wounds and wounds brought about by the predation of aquatic animals.

(6) Unless a body was found in clothes or wore items of jewelry that could be identified by friends and / or family some murder victims found in water might never be positively identified.

(7) The longer a body stayed in the water the more difficult it was to determine time of death, cause of death, and identity. During the Regency era this level of decomposition was of a much shorter time than today.

An interesting method of discovering a body in the water.

An ancient method for finding a body in the water, which was still in use well into the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was the use of quicksilver or mercury as we know it today. The quicksilver was inserted into a loaf of bread and floated as nearly as possible to where the body was supposed to have gone into the water. According to the superstition, the body would rise to meet the quicksilver. There is no scientific evidence to back this theory up. However, there are written records of the method being used.

The Gentleman’s Magazine, for April of 1767 contains a story about a search for the body of a child undertaken at Newbury in Berkshire where the one-year-old had fallen into the river Kennet and was drowned. The account states how the body was discovered by a very singular experiment—a two-penny loaf, with a quantity of quicksilver was put into the river and was set floating from the place where the child, it was supposed, had fallen. The loaf steered its course down the river before a great number of spectators. The loaf suddenly tacked about, and swam across the river, and gradually sank near the child, whereupon both the child and loaf were immediately brought up, with chained hooks ready for that purpose.