This is an oil painting of a pineapple grown in Sir Matthew Decker’s garden in Richmond, Surrey. The painting by Theodorus Netscher, made in 1720, is a celebration of the successful cultivation in England of a pineapple plant that actually produced fruit.

During the 18th century, a pineapple cost the equivalent of £5,000 today. They became such a symbol of wealth that the pineapple motif was used to decorate buildings – John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore, built a 75ft-high stone pineapple atop a pavilion in his estate in 1761 (below).

Though native to South America, pineapples (scientific name: Ananas comosus) made their way to the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, and it was here that Christopher Columbus first spotted their spiky crowns in 1493. Despite dogged efforts by European gardeners, it would be nearly two centuries before they perfected a hothouse method for growing a pineapple plant.

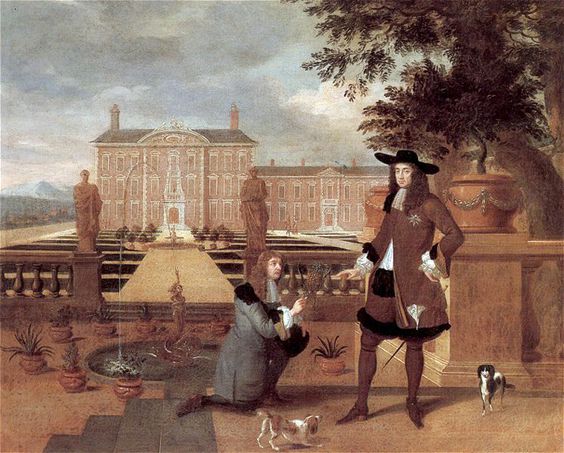

Thus, into the 1600s, the pineapple remained so uncommon and coveted a commodity that King Charles II of England posed for an official portrait (above) in an act then symbolic of royal privilege — receiving a pineapple as a gift. But was it a gift? Or had the pineapple been grown in his own hothouse? According to post entitled, “A pineapple? . . . Gosh, thank you Mr. Rose” on the Parks & Gardens UK blog, that question remains to be answered.

What is for certain is that on 9th August 1661 John Evelyn noted in his diary that he “first saw the Queene-Pine bought from Barbados presented to his Majestie…the first that were ever seen in England were those sent to Cromwell foure years since.”

Certainly plants must have survived the journey more than once, because King Charles used pineapples again on 14th August 1668, to impress the French ambassador, by serving them at a banquet held in his honour. Evelyn was there too and tasted “that rare fruite called the King-Pine” because ”his Majestie having cut it up, was pleased to give me a piece off his owne plate to taste of.” Sadly, Evelyn was mildly disappointed by the taste because “in my opinion it falls short of those ravishing varieties of deliciousnesse described in cap. liggons history & others but possibly it might be, and certainly was, much impaired in coming so farr. It has yet a graceful acidity, but tastes more of the Quince and Melon, than of any other fruite he mentions.”

Of course, all this assumes that it is John Rose in the picture. This attribution comes from Horace Walpole who had the original painting hanging in the Breakfast Room at Strawberry Hill. It features in his description of the house as ” a most curious picture of Rose, the royal gardiner, presenting the first pine-apple raised in England to Charles 2d, who is standing in a garden. The whole piece is well painted , probably by Dankers. It was a present to Mr W from the Rev.Mr Pennicott of Ditton, to whom it was bequestheed by Mr London, grandson of him who was partner with Wise”. [A description of the villa of Horace Walpole,1774].

Author Lucy Ingless tells us more about 18th century pineapple cultivation in an article on The Foodie Bugle:

“In 1735, twenty-one year old American Robert Hunter Morris accompanied his diplomat father on a trip to London and on the 30th of June visited a friend’s garden of ‘luctutious plants’ (does this mean succulents?), which included ‘the pineapple, of which he had a great many and they seemed to flourish very well. They grew in pots of earth which were set in a bed of tanners bark’. Incidentally, Robert was an interesting young character, who was very conscious of his father’s welfare and notes many tiny details about London life that would otherwise be missed. His London diaries are short and worth a read if you come across them.

“An article on education in the London World during 1755 makes casual reference to the pineapple thus:

“Through the use of hothouses…every gardiner that used to pride himself in an early cucumber, can now raise a pineapple.”

“By 1772, pineapples were no longer the preserve of those with hothouses of their own. They were available to purchase at the markets, and also as plants to take home and grow for yourself, or with which to stock a nursery. I love the sound of Andrew Moffett’s ‘Pinery’ on Grange Road in Southwark, where ‘Fruiting and Succession Plants’ were to be purchased of the largest and sweetest sort, guaranteed ‘free of insects’.

“As the 18th century went on, the pineapple became a common theme on dishes, plates, teapots, tea caddies and even in architecture. Many believe it symbolises hospitality.

“By February 1798, any problems with planting environment had clearly been overcome, as Mr William North, at his Nursery near the Asylum in Lambeth, Surrey, was advertising new forms of dwarf broccoli above his pineapple plants. The advertisement from the Morning Chronicle gives an insight into 18th century horticulture, and also gives rise to the excellent title of this post: “To the curious in vegetables”. It is interesting to see that by this stage, the pineapple was worthy only of a nota bene but also interesting to note that a London tradesman was content to advertise not only the largest selection in England, but also in Europe: The largest collection of Pine-Apple Plants and Grape Vines in Pots for the Hot-house, &c., in Europe, with every other article of the first quality in Horticulture.”

The pineapple entered the broader Georgian culture in a number of ways. The phrase ‘a pineapple of the finest flavour’ was a metaphor for the most splendid of things. In Sheridan’s popular play The Rivals, Mrs Malaprop exclaims: ‘He is the very pineapple of politeness.’

Even after growing pineapples on English soil became a possibility, getting hold of one was still so costly that many nobles didn’t eat them, opting instead to simply display them around their homes as one would a precious ornament or carry them around at parties. Those who weren’t quite as affluent could rent a pineapple for a few hours at a time. This pineapple would be passed around from renter to renter for their respective parties over the course of several days until finally being sold to the individual who could afford to actually taste it.

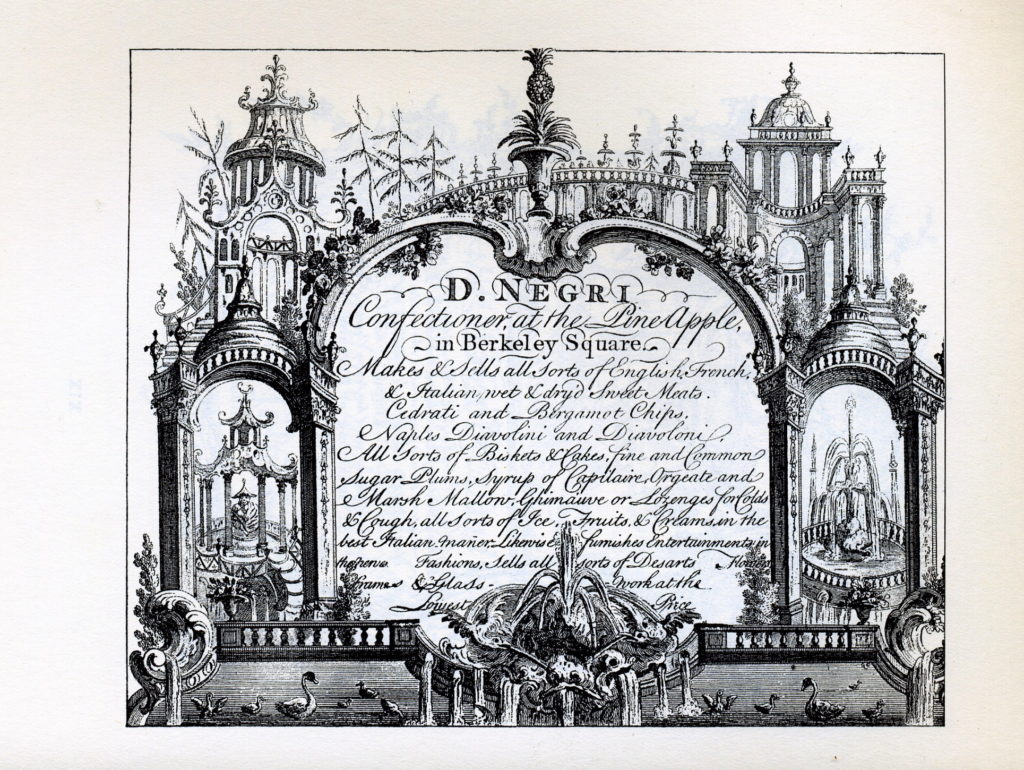

Pineapples held pride of place on dinner tables and on Negri’s tradecard below, the premises soon to be known by the name of “Gunter’s.”

There were also pineapple-shaped cakes, pineapple-shaped gelatine molds, candies pressed out like small pineapples, pineapples molded of gum and sugar, pineapples made of creamed ice, cookies cut like pineapples and pineapple shapes created by arrangements of other fruits. There were also ceramic bowls formed like pineapples, fruit and sweet trays incorporating pineapple designs, and pineapple pitchers, cups and even candelabras.

An original eighteenth-century pineapple pit was discovered at the Lost Gardens of Heligan in Cornwall. In 1997, after much historical research and horticultural effort, the pinery saw its first twentieth century fruit – grown just as it would have been done in the past. In a nod to Charles II, the second pineapple produced there (the first was sampled by the staff …) was delivered to Queen Elizabeth on her 50th wedding anniversary. For an in-depth and technical look at the structure of early English hothouses and the construction of a “pinery,” see this post on the Building Conservation website.

Click here to read more on age old growing techniques and the world’s most expensive pineapple.