|

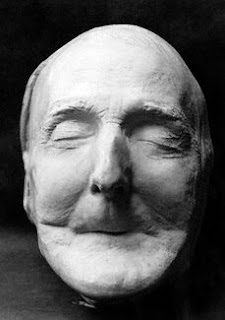

| Benjamin Disraeli |

|

| Sir Issac Newton |

|

| Viscount Henry Palmerston |

|

| Richard Brinsley Sheridan |

Originally published October, 2010

Recently, I came across a book online called The Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks: A Pictorial Guide by John Delaney, held in the Manuscripts Division in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at Princeton University Library. The making of death masks became popular in the 1800s, but the practice has much older roots. The first masks and effigies made in wax directly from the features of the deceased date from medieval Europe. Personally, I don’t get death masks. All of the people from whom death masks were taken were prominent people who had had numerous portraits and busts taken during their lifetimes. Why not remember them thusly, in the prime of their lives, rather than take an image of them in old age – withered, toothless and, more often than not, after having just suffered hours of agony? Perhaps my aversion to death masks is a woman thing. After all, I’ve yet to come across the death mask of a female.

|

| Making a plaster death mask, New York circa 1908, George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress |

I’d much rather remember, and hang on my wall, a picture of the Duke of Wellington looking like he does in the banner of this blog rather than like this:

In a volume titled, “The life of Richard Owen”, by Rev. Richard Owen (1894) there is reference to the death mask above in a letter written on November 13, 1852, to Mr. Thomas Poyser, of Wirksworth : ” I have been particularly favoured in respect of the remarkable solemnities in honour of the memory of the great Duke. The present amiable inheritor of the title called on me last Wednesday to request that I would call on him to see the cast that had been taken after the Duke’s demise, and give some advice to a sculptor who is restoring the features in a bust, intending to show the noble countenance as in the last years of the Duke’s life. It is a most extraordinary cast. It appears that the Duke had lost all his teeth, and the natural prominence of the chin and nose much exaggerates the intermediate space caused by the absorption of the alveoli. He of course wore a complete set of artificial teeth when he spoke or ate. My last impression of the living features is a very pleasing one. I brought it away vividly in my mind from Lord Ellesmere’s great ball last July.”

Napoleon’s Death Mask

Or is it? Is this the face of a short and rather dumpy fifty-one year old man? Napoleon died on May 5th, 1821, on the small island of St. Helena where he had been exiled for life after his shattering defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. A cast for a death mask was made by Dr. Francis Burton within a day and a half of Napoleon’s death. But, there was another doctor present at the time of Napoleon’s death, Dr. Antommarchi, who some say was mistakenly credited as the doctor who made the original mold. Immediately after the cast was made, it was stolen. It is believed that a woman named Madame Bertrand, Napoleon’s attendant, took the mold and sailed back to England. Dr. Burton tried but was unsuccessful in getting the cast back. Several years later a death mask turned up and was authenticated as being the original by Dr. Antommarchi, though historians have always argued against it, as the Antommarchi mask looked much too young to have been Napoleon, no to mention that bones of the face are heavier, the face itself longer and proportionally different when compared to the portraits that had been painted of the Emperor Napoleon. It is the official mask currently on display at Les Invalides in Paris, France.

Some believe that the death mask above was actually molded from the living face of the Emperor’s valet, Jean-Baptiste Cipriani. This is the mask that is thought to be authentic:

This death mask was on display at the Royal United Services Institute Museum in London for many years prior to 1973, when the mask was sold. You decide . . . . . here is one of the last portraits of Napoleon, painted by Sir Charles Lock Eastlake on board the ship Bellerophon.

And here is an enlargement of the face

Viola. Ze case it has rested. At least in my mind.

And the strange tales concerning death masks continue – It seems that there was once a special tunnel used to transport the bodies of the hanged from Worcester Gaol to the nearby Royal Infirmary, which stood across the road from the prison and has since been demolished. Until 1832, only criminals’ bodies were allowed to be dissected for medical research in the UK. The tunnel was found during work to transfom the former hospital into the new campus for the University of Worcester in the 1950’s – as were a number of death masks in the tunnel. These casts had been made to study the characteristics of the criminals’ personalities using physiognomy (shape and size of the head) and phrenology (study of the site of different abilities on the head), once thought to be useful in predicting criminal behaviour. The masks are now on display at the George Marshall Medical Museum in Worcester.

Perhaps the strangest story concerning a death mask – and physiognomy – is that involving Gershon Evan, who went on to live another 64 years after his mask was taken. In September 1939, 16 year old Evan was arrested along with 1,000 other young Jewish men and taken to Vienna’s Prater Stadium, where all were detained for weeks. Seeking out those with classic “Semitic” features, Nazi scientists — a commission of the anthropology department of the Natural History Museum — selected 440 men for study. Hair samples, fingerprints, hereditary/ biological appraisals and numerous photographs of the men were taken. The length and width of their noses, lips, chins and other facial features were meticulously documented. Evan was one of them. Soon after, Evan was ordered to submit to having a death mask taken.

“My head on the pillow, I stretched out on the table and closed my eyes,” he recalled in his memoirs years later. “The man advised me to relax, while he coated my face with a greasy substance. He applied it from the top of my forehead down to the throat and from ear to ear. The lubricant, he explained, was to prevent the hardened plaster of Paris from sticking to my skin.” At the end of the procedure, the death mask was removed, catalogued and archived. Evan was given a single cigarette for his troubles before being moved to Buchenwald, from where he was miraculously released four months later. At age 80, Evan was shown his preserved death mask and barely recognised himself in the youthful face held between the hands of a museum curator.

For more on death masks, including instructions on how to make one, visit Carlyn Becchia’s Raucous Royals blog.

A perfect post for the time of year. I really enjoyed it. I find death masks really intriguing, that mentality of cultural influence that would prompt someone to save an image of a deceased relative (or important figure). The same with daguerreotype photography, when surely one would have had other portrait photos taken in life.

There's an episode of a BBC series, How Art Made the World, that talks about death and the images of death we create, referencing the Jericho skulls. I'd hazard that the urge to keep the death images of important people (as opposed to loved ones who may not have had portraits) might be part of the coping mechanisms the episode talked about. Seeing famous dead people, and remembering that they too have died, helps us comes to terms with our own inevitable death and make it a reassuring rather than terrifying prospect.

As for death masks of women (a great point!), the only one that comes to mind for me is L'Inconnue de la Seine. Even if the mask isn't truly of a drowned woman, it still became quite popular. Of course, all the subtext around it is just begging to be unpacked 🙂

Hayley – What insightful comments, thanks for taking the time to share them. I hesitated in mentioning L'Inconnue de la Seine in the post, as the consensus seems to be that it's not real, as you pointed out. That was the only reference I could find to female death masks. As to mourning photography . . . tune in tomorrow!

Wow! Great post for the Halloween weekend! And fascinating. I find the idea of death masks of hanged criminals especially fascinating. The idea that someone's features or the shape of their head could determine criminal behavior is interesting.

Great stuff, as usual, ladies!

I enjoyed this post the first time and it is completely appropriate for this time of year. Like you I prefer to remember Artie the way he is in those great paintings, like the one in the postcard I have framed on my desk. It is there to remind me that someone who was thought to be of little consequence (aka cannon fodder) can sometimes change the world.