By Guest Blogger Regina Scott

Once more we return to the boxing square! If you missed part one of this series, you can find it here. And part two is here.

As you can imagine, there were a great many gentlemen in the Regency period, but only one man known as The Gentleman. Gentleman John Jackson was born in 1769 to a Worcestershire family of builders. He decided at age 19 to become a boxer, much against his parents’ wishes. With the awe he ultimately inspired in just about every fellow of substance, including the Prince Regent, it’s surprising to find that he only fought professionally three times, and one of those he lost. However, as the other two times he fought men who were considered top champions, he was known in his time as the heavy-weight champion of England. He held that title for one year, in 1795, after beating Daniel Mendoza—nicknamed The Jew—who had held the title the previous two years.

When Jackson retired, Thomas Owen beat all comers to gain the title in 1796, followed by Jack Bartholomew (1797 to 1800), Jem Belcher (1800 to 1803), and “Hen” Henry Pearce the Game Chicken (1803 to 1806). After Hen retired, John Gully beat all comers and reined for two years before opening his own school in London. Belcher was also known for taking on pupils.

So why was John Jackson held as the “best”?

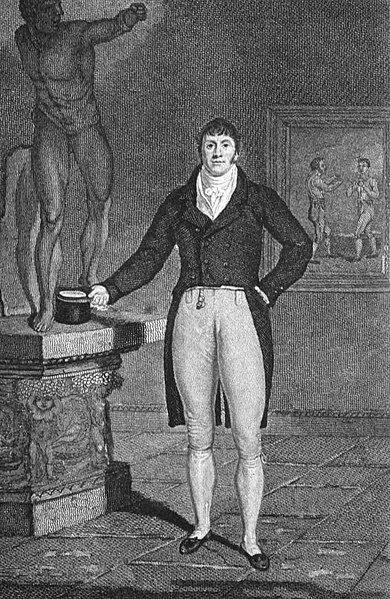

For one thing, he appears to have been a splendid specimen of masculinity. At 5 feet 11 inches tall and 195 pounds, his body was said to be so perfectly developed (with the Regency idea of “perfection” being the statues of the Greek gods), that artists and sculptors came from all around to use him as a model. For another, he dressed well (although he favored bright colors) and spoke in cultured tones, making him the darling of the ton. His two flaws in looks were that he had a sloping forehead and ears that stuck straight out from the sides of his head. Presumably, the sculptors and artists used someone else to model the head.

Besides being the man to whom every gentleman, including Lord Byron, went for lessons, Jackson is credited with keeping the sport honest in a time when bouts were often fixed. He developed the equivalent of the Boxing Commission in the Pugilistic Club, which collected subscriptions from wealthy patrons and sponsored fights several times a year. For each fight, a Banker was appointed to hold the purse as well as many side bets that might be made. Jackson was often nominated for this position.

So great was his prestige that Jackson was called on to arrange pugilistic demonstrations for the aristocracy, including fights before the Emperor of Russia, King of Prussia, Prince of Wales, and Prince of Mecklenburg. At the 1821 coronation of George IV, Jackson furnished a group of pugilists to act as guards to keep lesser mortals at bay.

The Gentleman bowed out of this world on October 7, 1845. But he left a legacy that endures to this day.

Regina Scott is the award-winning author of more than 40 works of sweet historical romance, several of which feature Regency gentlemen who box. In her recent release, Never Kneel to a Knight, a boxer being knighted for saving the prince’s life must prove to a Society lady who is miles out of his league that their love is meant to be.

You’ll find more on Regina online at her website, on her blog, or on Facebook.