by Louisa Cornell

Anyone who writes romances set in Regency England must have a thorough knowledge of that quintessential piece of British architecture – the English country house. One of the best resources for the study of these monuments to old titles and often older money is the country house guidebook. They usually include photographs of the most beautiful rooms, and more often than not, a floor plan of the house. I have an ever-increasing collection of these guidebooks, many for homes I have not visited. Yet. Frequent visits to Amazon used books and Ebay make adding to my collection easy. And I have friends who enable my addiction by bringing these books back from their trips to England for me.

Elizabeth I actually set the wheels to the country house tour in motion. Whilst her father made pilgrimages to tour his own homes, Elizabeth I often traveled England visiting houses of the nobility. Therefore, as early as the Elizabethan age, the aristocratic pattern of building large country houses for the sake of display and prestige was set by these royal pilgrimages.

In the Georgian era, the increasing wealth of the expanded upper classes provided time for travel and cultural pursuits. More and more turnpike roads were created, making travel faster and safer. Inns were built to accommodate tourists. By the end of the 18th century clergymen, lawyers, military officers, bankers, merchants, minor landowners, and members of the aristocracy were all making tours.

Frequent wars on the Continent thwarted traditional Grand Tour Destinations. Even without wars, travel for women was restricted. Visiting other ‘good’ families was an acceptable way to broaden their knowledge and tastes – cross pollinating ideas, styles, and fashions.

Houses near large conurbations were especially susceptible. Walpole’s neo-Gothic Strawberry Hill near Twickenham was a particularly sought out destination. When visiting an area, day trips to nearby country houses were a favorite activity. The expectation was an owner would, as part of their duty to better society, open their house. Part of being a polite land owner was allowing tourists to visit one’s house and grounds. Key questions in planning these visits were – find the houses, determine whether the owners were amenable to visitors, no matter how genteel. Areas with a higher density of fine houses, within a day or two ride of a city or other existing tourist destinations – Norfolk, Derbyshire, Wiltshire – became part of the unofficial British Grand Tour.

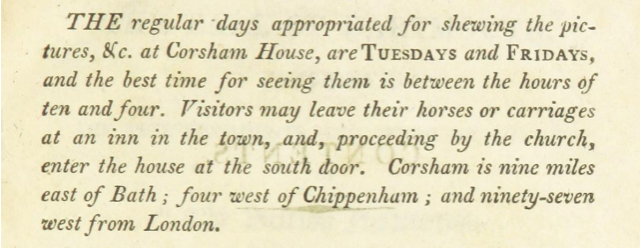

By the latter part of the 18th century the number of people visiting country houses had grown exponentially. As these numbers increased so did the need to manage the situation. Some owners simply refused visitors access. By 1760, Chatsworth was specifically open two days per week.

In 1774, Walpole began issuing tickets and rules for good conduct. He only allowed a maximum of four visitors per day, and children were absolutely forbidden. Smart man. He wrote his own guidebook and printed them on his own printing press. He seldom gave them out as he was afraid people would never leave should they try to see everything he described in the guidebook.

Frontispiece to A Description of the Villa

at Strawberry Hill

Only a handful of houses attracted hundreds of visitors. Wilton House in Wiltshire was one. The increase in visitors eventually led to formal opening hours and standardized tours led by housekeepers. Inns were built near to these houses to cater to tourists.

Internal tours were conducted by the housekeeper.Whilst their stories of family history might or might not be true, their information about works of art and collections in the house were more often than not quite wrong. Some housekeepers were even rumored to simply make things up. Demand for more accurate information gave birth to the concept of the guidebook. In the beginning, the standard form of these guidebooks was a map of an agreed upon route through the home,with entries on each work of art. Indeed most of the ones from the 1730’s and 1740’s were in-house creations with the aforementioned maps, i.e. a floor plan with a suggested route through the house. All of them were focused on an individual house and were basically a catalogue of the artworks and collections in the house.Usually published after a house became established as a tourist attraction, they included information about those things visitors were expected to notice. And, of course, they excluded those things visitors were expected to ignore.

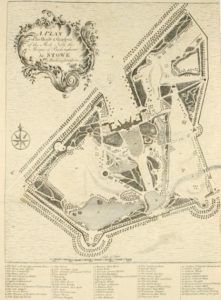

Only a handful of houses had their own guidebooks before 1800. In 1774 Benton Seeley’s guide to the House and Gardens at Stowe was the first to be published by an outside publisher. It ran to twenty editions in sixty years.

Early guidebooks not designed in-house were published to take advantage of the new market and to build on tours available at multiple country houses. They were designed to be practical for travelers – small, lightweight, simply bound pamphlets with marbled paper covers. They were comprised of information about the house and gardens – according to the paths visitors were expected to take. The guidebook to Hawkstone in Shropshire provided information about various views and spaces of the renowned gardens there.

Places popular with the 18th and early 19th century visitors were :

Stowe, Buckinghamshire – It was the first to attract visitors in significant numbers, to have its own inn, and to have its own guidebook. It was primarily famous for its gardens.

Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire – It was known for its art collection. It offered impressive tours conducted by the housekeeper. It was considered one of the first “modern” stately homes as its interiors were the work of Robert Adam.

Stourhead, Wiltshire – One of several popular houses in Wiltshire, it could easily be included in a tour of the West Country. Visitors came to see the gardens, the park, and the fabulous ‘Pope’s cabinet’ on display in the house.

Studley Royal Water Garden, North Yorkshire – Studley was most known for its gardens and its connection to the ruins of Fountains Abbey,which was purchased by the Aislabie family in 1767. However, visitors were rarely admitted to the house.

As outside publishers realized the value of these guidebooks they were designed to be more functional. They came in small octavo form, bound in paper covers, lightweight and inexpensive. They were sized in easy to carry forms to be used as one toured the house. Their appeal as a souvenir was heightened by the addition of illustrated frontspieces – the most common being images of the house. The most elaborate guidebooks included a series of illustrations. Some editions of the guide to Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire included a fold-out map of the gardens, often with hand-colored details, and a set of views of the house.

Booksellers began to see the value in guidebooks and before long rival booksellers were publishing guidebooks of the same house. Eventually they became available in London bookstores as well as in the shops near the houses themselves. People began to read them whether they ever intended to visit the houses or not. The guidebooks began to include a wider range of information. They began to describe the surrounding countryside, details about the family, an architectural history of the house – which included information about everyone from the architect to the plasterers and other artisans involved in the creation of the house. And, of course, they also served as catalogues of the works of art and collections assembled in each house.

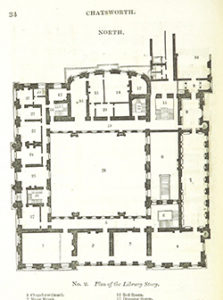

Eventually, writers took on the task of writing guidebooks for specific areas, such as Stephen Glover’s The Peak Guide published in 1830. He was among the first to write a guidebook for an area, rather than an individual house. However, his book does include extensive entries on houses in the area. The entry for Chatsworth is over 37 pages and includes detailed entries on important paintings and the artists who painted them.

‘Plan of the Library Story’ from ‘The Peak Guide; containing the topographical, statistical, and general history of Buxton, Chatsworth, Edensor, Castlteon [sic], Bakewell, Haddon, Matlock, and Cromford’ by Stephen Glover of Derby [1830]

The country house guidebook has come a long way and has undergone numerous permutations to become the stylish, slim, photograph-heavy little books sold in the souvenir shops and village booksellers in and around Britain’s stately country houses. They began as and continue to be important sources of information about the treasures, mysteries, histories, and families of these magnificent microcosms of British history.