by Victoria Hinshaw

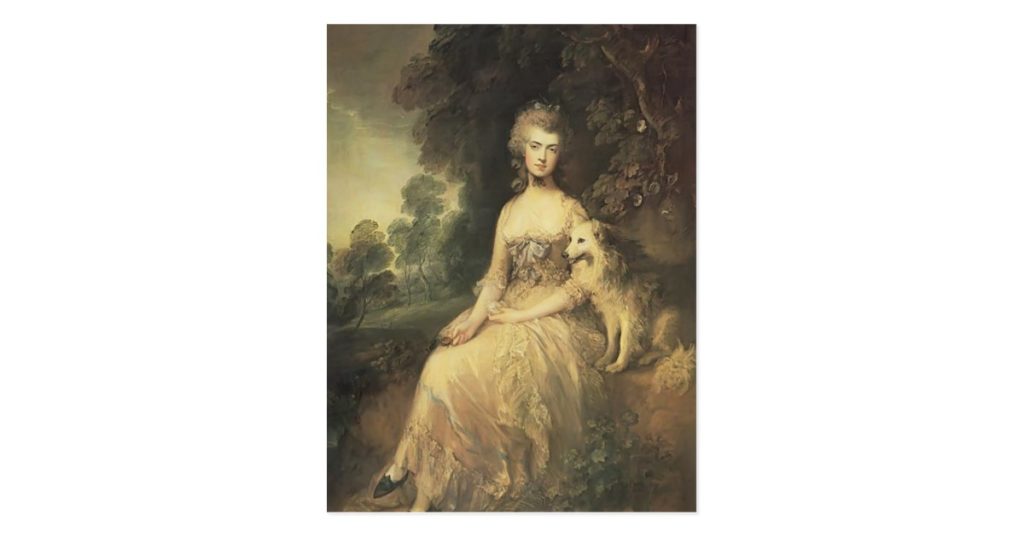

In 1781, Mary sat for a portrait by Thomas Gainsborough, commissioned by the Prince. In this version of the painting in the Wallace Collection above (another is in the Royal Collection), Mary holds a miniature of the Prince in her right hand.

Mary had only a brief time in the limelight of the London demi-monde. Only a few year later, she was reported to be “desperately ill.” Various explanations for her condition have been suggested, but the causes of her maladies remain mysterious. In May of 1791, she published a book of poems, “a small but handsomely bound volume with marbeled end papers,” made possible by sums raised by 600 subscribers, including the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York, the Duke of Clarence and many other luminaries.

In 2010, Kristine and Victoria, along with Kristine’s daughter, Brooke, visited with Hester Davenport in Windsor, here at the Castle.

Hester Davenport chronicles the reception Mary’s book received. Readers seem to ask, “How was it possible to connect the frivolous woman of 1780s gossip with a writer of pensive odes, elegies and sonnets?” That Mary acquired the title ‘The English Sappho,’ possibly at her own instigation, may have added to the this (seductive) sense of being wooed.

Mary lived only a few more years, dying in 1800, having never recovered her health. She had, however, continued to write poetry as well as her memoirs, several novels, plays and feminist essays.

As an endorsement of the value of her literary work, the painting of Mary Robinson by Hoppner, above, was acquired for the Chawton House Library, where it is displayed prominently. Many works by Mary Robinson are available from their website. Her biography is here.

We all hope that future scholars will pay attention to this fascinating woman and her body of work. In the epilogue of her biography, Hester Davnport writes, “Mary Robinson was dead: the talented actress, spectacular Cyprian, accomplished and industrious author, committed feminist and radical, charming and witty hostess, spendthrift, devoted daughter and mother, compassionate, sensitive and sometimes spikily difficult woman. A genius? Perhaps only in her extraordinary versatility, but not undeserving of the ‘One little laurel wreath,’ she craved.”

The exquisite Hoppner portrait is currently featured (with others) in the First Actresses exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. Not only is it the cover art of the accompanying book, it's also the official poster. Perdita has popped up all round London!

What a fascinating woman. And very much her own person. A woman had to be tenacious of spirit to survive as an actress and courtesan in nineteenth century England. Perdita was such a woman.

Hester and I wrote about women who fascinated us. She has written this biography of Mary Robinson (and also one of Fanny Burney) and I wrote a bio of Grace Dalrymple Elliott. I met Hester when my publisher sent her the galley of my book. (I had aready read her wonderful book on Perdita.) It's a small world, as we all know, especially the world of female biographers of women 🙂 Grace was the lifelong rival/enemy of Perdita, as she had replaced Perdita (there was at least one woman in-between) in the Prince's bed.

In my opinion, Hester's bio remains the best of the three that were published within months of each other. Extremely well researched! And Hester lives down the road from the churchyard where Perdita lies buried. (I, alas, could never find Grace's grave, but my France-based researcher did, in Pere Lachaise cemetary. The tombstone, however, is gone 🙁

Thank you, Hester, for a wonderful story of a remarkable woman! (You all must read her book for more on Perdita's fascinating — and tragic — life.)