Napoleon After Waterloo

Andrea K. Stein

Bellerophon was a famous Greek hero, mostly known for defeating Chimera, a fire-breathing, mythical monster. By some quirk of fate and history, the H.M.S. Bellerophon was also the name of the ship where the monster Napoleon, who bloodied two continents in his obsession to rule the world, turned himself over to the Royal Navy after his defeat at Waterloo.

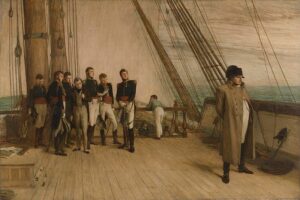

Painting by John James Chalon

Stories surrounding the final, decisive battle of Waterloo abound, but have you ever heard an account of what happened to the little megalomaniac emperor in the days following his massive defeat? He somehow thought after all the horrors he’d wrought, everyone would overlook his misdeeds. He variously dreamed of living the life of a country gentleman in England or managing an escape to America.

Napoleon fled to Paris after the June 18, 1815, battle, arriving there on June 21. When he tried to rally what troops he had left, his friends and commanders either abandoned him or turned against him. He had to abdicate two days later. He then fled to Rochefort in the coastal area known as Basque Roads. He’d hoped for a French frigate to take him to asylum in America, but the Royal Navy blockade of the area was too tight for French ships to evade. With French Royalists hot on his heels, he ran out of options, and on July 15, he surrendered to Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland on the Bellerophon.

With its famous prisoner aboard, the Bellerophon, heavily guarded by other Royal Navy warships, made its way to Brixham in Devon, arriving the morning of July 24. John Smart, a schoolboy who later wrote a memoir of the day, described rowing out to the 74-gun ship with a baker from the town to sell loaves of bread. They were warned away, but he claimed a sailor aboard the ship secretly threw a corked bottle overboard with a small piece of paper inside rolled up with the message, “We have got Bonaparte on board.” Smart recalled, “in five minutes after we reached shore, there was not a soul in Brixham, except babies, ignorant of the news.”

Ultimately, the allies decided to send him to remote St. Helena, a rocky island about halfway between Africa and South America, owned by the East India Company. Why didn’t they simply execute him? Perhaps this quote from Wellington might shed some light:

The Duke of Wellington to Sir Charles Stuart, Orvillé

28 June 1815—

“I send you my dispatches, which will make you acquainted with the state of affairs. You may show them to Talleyrand if you choose.

General ——— has been here this day to negotiate for Napoleon’s passing to America, to which proposition I have answered that I have no authority. The Prussians think the Jacobins wish to give him over to me, believing that I will save his life. Blücher wishes to kill him; but I have told him that I shall remonstrate, and shall insist upon his being disposed of by common accord. I have likewise said that, as a private friend, I advised him to have nothing to do with so foul a transaction; that he and I had acted too distinguished parts in these transactions to become executioners; and that I was determined that if the sovereigns wished to put him to death they should appoint an executioner, which should not be me.”

Napoleon’s charisma, and his effect on the people around him, is legendary, not to mention somewhat hard to fathom. Captain Maitland of the Bellerophon, to whom Napoleon surrendered, wrote this in his memoir of the event:

“It may appear surprising, that a possibility could exist of a British officer, being prejudiced in favour of one who had caused do many calamities to his country; but to such an extent did he possess the power of pleasing, that there are few people who could have sat at the same table with him for nearly a month, as I did, without feeling a sensation of pity, allied perhaps to regret, that a man possessed of so many fascinating qualities, and who had held so high a station in life, should be reduced to the situation in which I saw him.”

Captain Maitland was not alone in his apparent fascination. The former French emperor so charmed the ship’s Irish surgeon, Barry Edward O’Meara, that he accompanied Napoleon to St. Helena and became his physician there. After Napoleon’s death in 1821, O’Meara wrote Napoleon in Exile, or A voice from St. Helena in 1822. His allegations of mistreatment of the former emperor by his gaoler, Governor Hudson Lowe, caused a small sensation back in England as well as the rest of Europe.

Letters leaked to newspapers while Napoleon was still alive, about alleged deprivations such as insufficient firewood, caused an uproar among the very people who suffered throughout the Napoleonic Wars. The imprisoned dictator who’d wanted to conquer the world seemed to evoke romantic notions once he’d been exiled.

However, there were also many Britons who voiced strong opposing opinions, as evidenced by this letter published by The Times on July 26:

“What is to be done with him? Is he after all his crimes to be suffered to go unpunished; or in what way is he to be brought to justice?… He has, for a long succession of years, deluged Europe in blood, to gratify his own mad vanity, his insatiable and furious ambition. It is calculated, that every minute he has reigned, has cost the life of a human being…”

A lieutenant taking dispatches to London from Brixham spread the news while changing horses in Exeter. By the next day, the Bellerophon was surrounded by all manner of craft from local ports, and even further away, hired by people trying to catch a glimpse of Napoleon.

Officers going ashore from the ships were treated like celebrities. One Midshipman Home recalled he was asked questions like “Was he really a man? Were his hands and clothes all over blood when he came aboard. Was his voice like thunder? Could I possibly get them a sight of the monster?” The former emperor had been portrayed as the devil incarnate in stories and caricatures in the English papers for years.

The Admiralty decided the Bellerophon should be moved to Plymouth for extra security against any rescue attempt. On July 31, a letter arrived with the official decision of the British government – exile to St. Helena. The former emperor was to be transferred to the Northumberland, a ship the Admiralty deemed more sea-worthy for the long voyage. On August 4, the Bellerophon set sail from Plymouth along the south coast of Devon where it met the Northumberland off Start Point on August 6 for transfer of Napoleon and his entourage. The next day, he sailed toward his last exile.

After his final imprisonment, there was one cork-brained plan to smuggle him to Chile from St. Helena to try to re-conquer the world from there. That plan never materialized, due to Napoleon’s deteriorating health. An attempt to spirit him off the remote island by submarine was also cut off when British agents seized the invention whilst being tested in the Thames. The submarine, manufactured by Tom Johnson, the smuggler, was ostensibly to be towed all the way to St. Helena by a larger ship.

Sources:

“The War for all the Oceans” by Roy and Lesley Adkins

“Commander” by Stephen Taylor, a biography of Captain Edward Pellew

“Cochrane – Britannia’s Sea Wolf” by Donald Thomas

“The Command of the Ocean” by N.A.M. Rodger

“Narrative of the Surrender of Buonaparte and of his residence on Baord H.M.S. Bellerophon” by Captain F.L. Maitland, C.B.

AUTHOR – ANDREA K. STEIN

Andrea K. Stein is the daughter of a trucker and an artist. She grew up a scribbler. The stories just spilled out.

After writing and editing at newspapers for twenty-five years and then a short, boring stint as a consultant to commercial printers, she ran away to sea for three years to deliver yachts up and down the Caribbean.

She earned her USCG offshore captain’s license, but perversely, now writes romance set at sea while wrapped in sweaters and PJs in her writing room in Canon City, CO.

She has multiple published romance novels available on Amazon. Three of those titles have been honored with awards. “Secret Harbor” earned a first place in the Pikes Peak Writers Fiction Contest in the romance category; “Fortune’s Horizon” finaled in the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers Romance category; and the latest novel, “Pride of Honor,” finaled in the national 2018 Beau Monde Royal Ascot Contest.

Book Three in The Men of the Squadron Series – PRIDE OF VALOR – Debuted on February 23, 2021. Visit your favorite purveyors of fine books and spend some time with the Men of the Squadron!