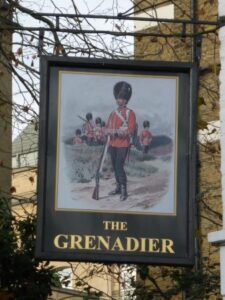

Tucked away down London’s exclusive Wilton Mews, on the corner of Old Barrack Yard, the patriotic Grenadier pub is painted red, white and blue and boasts a red sentry box that serves as a nod to the property’s military history. Reputedly, the Duke of Wellington’s Grenadier Guards used it as their mess. Inside it is small, dark, and cozy, the paneled walls covered with military and Wellington memorabilia. Reputedly, the pub’s upper floors were once used as the officers’ mess of a nearby barracks, whilst its cellar was pressed into service as a drinking and gambling lair for the common soldiers.

A display at the entrance to the pub informs us that “18 Wilton Row was built circa 1720 as the home to the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards regiment and famously known as the Duke of Wellington’s Officers Mess. Originally named The Guardsman as a Licensed Premises in 1818, and frequented by King George IV, the Grenadier enjoys a fine reputation for good food and beer.” From the same display we also find out that the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards was created in 1656, and that 1st Guards were renamed by Royal Proclamation as the ‘Grenadier Regiment of Foot Guards’ because of their heroic actions against French Grenadiers at Waterloo in 1815. Continuing the Wellington connection, directly outside in the old Barrack Yard at the side of the pub is what is reputed to be the remaining stone of the Duke’s mounting block, whilst an archway down the nearby alley forms part what was once the barrack stables.

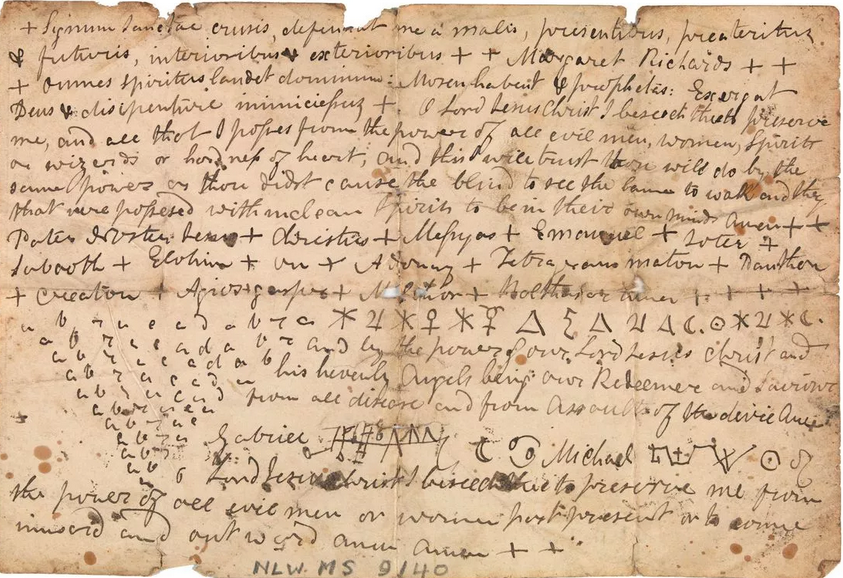

Here, a young subaltern is said to have once been caught cheating at cards, and his comrades punished him with such a savage beating that he died from his injuries.

The Grenadier is said to be one of the most haunted places in London. People who have worked there have quit after supernatural run-ins with a solemn, silent spectre reportedly seen moving slowly across the low-ceilinged rooms. Objects either disappear or else are mysteriously moved overnight. Unseen hands rattle tables and chairs, and a strange, icy chill has been known to hang in the air, sometimes for days on end. A ghostly face floats in an upstairs window and – the most common tale – the sentry box out front is haunted by the ghost of the dead subaltern.

So . . . a few years ago, on Saturday, August 3, 1996, I was at the Grenadier with Sue Ellen Welfonder (Bozzy) and two other women whom I won’t name because I haven’t seen them in years and have no idea whether or not they want to be associated with the following story. I don’t often talk about it myself, as it makes one seem as odd as those who claim to have been abducted by aliens or to have seen the Loch Ness Monster and Big Foot. We, Reader, saw ghosts. Not a ghost, but a circle of ghosts. Regency soldier ghosts, no less.

We could see that the alley beside the Pub led back to a yard with stable doors and a row of quaint single story houses along one wall. Very atmospheric, very historic . . . very tempting. What was back there? we asked. Let’s go look! we answered. What. A. Mistake. As you can see by the photo, a sort of alley runs beside the Pub and opens up at the end to the barrack mews.

We walked down the alley to the end, where the car is visible in the photo below. There was a car parked in the very same spot on the night in question. We got to the end of the alley and saw . . . . . a ring of ten to twelve men – soldiers, whose red coats had been thrown in a pile atop the cobbles. They wore breeches and boots and white shirts. They stood in a circle in the space between the front of the car and the stable doors – surrounding a man who was on his knees at the center of the circle, his face already bloody and bruised from the beating that had already been going on for some time (centuries?). These men were pissed off. Even taking into account the fact that cheating at cards was a much more serious offence then than it is today, their anger was beyond anything justified by such an offence.

We watched them as though we were watching a black and white film that was being played at half strength. That’s the only way I can describe it. The scene was playing out before our eyes, in the bricked space between the car and the black stable doors, the men utterly oblivious to our presence. The film ran for a minute, probably less in hindsight, and then flickered out. Except this film had something extra – this one had been filmed in “emotion-vision.” As we watched the ghostly events, each one of us could actually feel the anger and the venom that was being directed towards the poor schmuck on his knees in the middle of the circle. In fact, I think the strength of that collective emotion was more overwhelming to us than the fact that we’d actually just seen ghosts. The experience was so shocking, so unbelievable that I will be forever grateful that I was in the company of others when it happened or else I’d truly doubt whether it had taken place.

I suppose seeing ghosts is much like childbirth – the true horror of the experience abates with time and twenty-six years have since passed. I’ve been back to the Grenadier many times since, both alone, with friends and with tour groups. More recently, I’ve even ventured back into the mews and I’ve been taken into the private areas upstairs. I’ve never seen the ghost soldiers on the premises again, though several members of staff emphatically refuse to go down to the cellars. And just as emphatically refuse to discuss why.

This post originally ran in 2010 and has since been updated by the author.

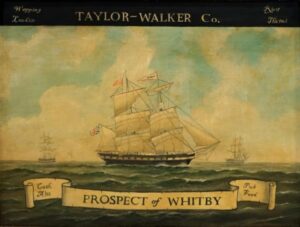

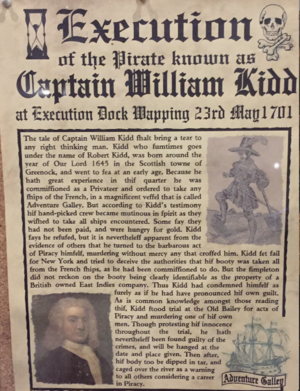

The most famous criminal hanged at the execution dock at the Prospect of Whitby was Captain William Kidd. Ironic, as the Scottish sea captain was originally appointed by the Crown to hunt down pirates. He discovered piracy was much more profitable than hunting down pirates. He did quite well for a while. Unfortunately, in 1698 he captured The Quedagh, which was sailing under a French pass. The captain, however, was an Englishman and the rich cargo Kidd took was property of the East India Company. Kidd was eventually captured and brought back to London where he was sentenced to death for piracy and for the murder of one of his own crewmen (in 1697) who had dared to cross him.

The most famous criminal hanged at the execution dock at the Prospect of Whitby was Captain William Kidd. Ironic, as the Scottish sea captain was originally appointed by the Crown to hunt down pirates. He discovered piracy was much more profitable than hunting down pirates. He did quite well for a while. Unfortunately, in 1698 he captured The Quedagh, which was sailing under a French pass. The captain, however, was an Englishman and the rich cargo Kidd took was property of the East India Company. Kidd was eventually captured and brought back to London where he was sentenced to death for piracy and for the murder of one of his own crewmen (in 1697) who had dared to cross him.