LOUISA CORNELL

Ghost stories abound from one end of England to the other. Whether born of local legend or eyewitness accounts, a country with so long and an often violent history should not be looked at askance when the subject of ghost stories and other supernatural occurrences come up.

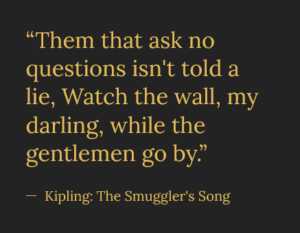

However, there are some very specific tales of ghosts and beasties indigenous to England’s coast that served a very specific purpose. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries the business of nearly every inhabitant of every village along the coasts of Cornwall, Devon, Essex, and Kent was in some way connected to the smuggling trade. The most important part of the trade involved making certain the movement of goods brought over from the Continent by ship made it from said ships to shore and then to their final, lucrative destination without being seen, especially by any agents of the Crown patrolling the area in search of goods smuggled into the country without benefit of the Crown collecting the appropriate taxes.

Numerous tricks and methods of subterfuge were used to make certain the transport of smuggled goods was not detected. But perhaps no method was more creative than the spinning of ghost stories and legendary specters meant to frighten the locals from venturing out at night, when most of this transport took place, and putting a scare into the customs men and excise riders whose job it was to stop them. Remember in this era superstition and connection to the world on the other side of the veil was not only part of the average citizen’s psyche it was also still woven into the fabric of the nation’s spiritual life.

Here are a few of those tales. Judge for yourself!

At Hadleigh Castle a pair of ‘phantoms’, – the White Lady and Black Man – made dramatic appearances just before a shipment of illicit liquor arrived, and duly disappeared when all the liquor had been moved away.

There is no doubt that the famous 18th century legend of ‘the Ghostly Drummer of Hurstmonceaux Castle’ in Sussex started with some enterprising smugglers and a little phosphorus!

The Saltersgate Inn, previously known as the Wagon and Horses stood in an elevated position on the moors, on what is now the main road between Pickering and Whitby, with its name thought to originate from the salting of fish which is believed to have taken place here. The name of the inn could potentially have been derived from the Yorkshire word ‘Yate’ meaning road, therefore ‘Salters Road’. It is said that one night, a customs official, on finding out that illicit trading activities were taking place at the inn, was murdered by smugglers and his body buried beneath the fireplace. It was said that if the fire was ever to stop burning, then the ghost of the murdered officer would return to haunt the inn.

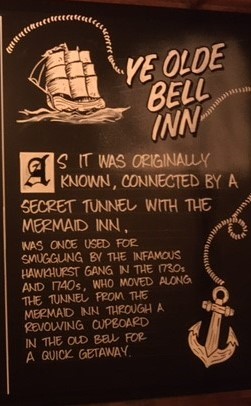

The Old Bell has been around for a very long time, originally starting life as a hospice and hostel that was run by monks during the Norman conquest nearly 1000 years ago. A ghost of a middle-aged man was said to sit beside the fireplace in the dining area. Beer barrels were said to be supernaturally re-arranged in the cellar of the Bell overnight when the tavern was closed, and in the grounds of the pub the ghost of a civil war Royalist Cavalier and his horse was reported. It’s hard to not miss the fact that in some cases the stories of ghosts were actually invented by smugglers themselves to keep people away from certain buildings. And The Old Bell was known to be an overnight stop for some of the brandy and rum coming over from France.

The ghostly tales of the Mermaid Inn are extensive and are hardly surprising considering the history of the building. The Elizabethan chamber, also known now as Room 16, reportedly hosts two figures dueling, without making a sound. They were both armed with rapiers and they were both well dressed in hose and doublets. Eventually one was dealt a fatal thrust and appeared to die, the winner of the duel takes a nervous glance around the room before dragging the body of his opponent to a nearby tarp door and disposing of it!

Another tale tells of the room now known as The Hawkhurst Room, namesake of the Hawkhurst Gang where a man dressed as a smuggler sits on the bed in the middle of the night.

Where doesn’t have a white or grey lady story in it’s history? The Mermaid has a few different shaded ladies in residence. A lady in white is said to haunt the inn (busy place) said to walk from the single room and across to the main room of the Nutcracker Suite then straight through the door while stopped for a moment at the foot of the bed. This lady in white has been said to be the spirit of a girl who made the mistake of falling in love with one of the many smugglers of the area during the 1700’s. Apparently though she was very chatty which as we should know by now the smuggling gangs were not keen on, especially when the chat was about their business. Hardly surprising that they were said to have murdered her for talking too much. She’s said to still wander the rooms in death, forever searching for her lover. There’s also been many reports of a lady wearing white or maybe grey who is seen sitting by the fireplace in a chair in what is now Room One. Guests apparently report getting wet clothes if they leave them on this chair overnight despite the lack of windows or even pipework near the chair.

One room in the Mermaid is said to have lots of reports, apparently all around Halloween many of a rocking chair which moves of it’s own accord as the temperature of the room plunges, in fact this has been said to be so unnerving that maids would only clean this room if with a colleague. One worker reported seeing the chair rocking quickly and seeing the cushion compress as if a live person was sat on it…but invisible. Some that have stayed in the room have reported hearing someone walking around the bed but there being nobody there upon inspection.

Other Supernatural Abettors to the Smuggling Trade

A mysterious herd of horses were said to guard the smugglers’ way up from the beaches of Cornwall. Fierce horses with fiery red eyes and hooves that sparked when they touched the ground were said to appear out of the mists to anyone foolish enough to travel those paths at night, especially on stormy nights known as “smugglers’ weather.”

Several smugglers’ villages had a local hell hound who guarded the local cemetery from customs men and excise riders and anyone else foolish enough to venture there after dark. Why? Because another stop on the smuggler’s route was often the tomb of a local wealthy family where the goods might be stored until they could be divided up to be sold. Again the ferocious black dogs had red glowing eyes, fangs dripping blood, and were said to to be the size of a small bull.

Ghostly owls were also part of a smuggler’s arsenal to keep prying eyes from their business. As owls were often associated with witches this threat was a twofold weapon. Especially as smugglers often used owl calls to communicate with each other!

What does this all mean? These stories, often created by the smugglers themselves, were a very real and very effective deterrent to detection! Were these ghosts and apparitions real or did they have any basis in fact? That’s the question, isn’t it?

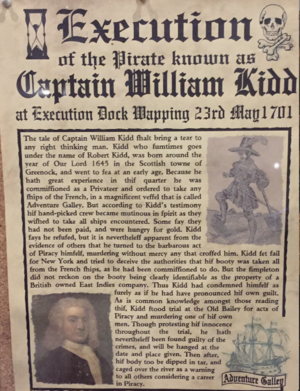

The most famous criminal hanged at the execution dock at the Prospect of Whitby was Captain William Kidd. Ironic, as the Scottish sea captain was originally appointed by the Crown to hunt down pirates. He discovered piracy was much more profitable than hunting down pirates. He did quite well for a while. Unfortunately, in 1698 he captured The Quedagh, which was sailing under a French pass. The captain, however, was an Englishman and the rich cargo Kidd took was property of the East India Company. Kidd was eventually captured and brought back to London where he was sentenced to death for piracy and for the murder of one of his own crewmen (in 1697) who had dared to cross him.

The most famous criminal hanged at the execution dock at the Prospect of Whitby was Captain William Kidd. Ironic, as the Scottish sea captain was originally appointed by the Crown to hunt down pirates. He discovered piracy was much more profitable than hunting down pirates. He did quite well for a while. Unfortunately, in 1698 he captured The Quedagh, which was sailing under a French pass. The captain, however, was an Englishman and the rich cargo Kidd took was property of the East India Company. Kidd was eventually captured and brought back to London where he was sentenced to death for piracy and for the murder of one of his own crewmen (in 1697) who had dared to cross him.