One of the reasons I wanted to return to Waterloo was to see the new museum and exhibits that were put in place for the celebrations of Waterloo 200. The photos above in no way do justice to the scale and scope of the exhibits. The huge hall in the top photo displays a soldier from all of the British regiments on the right, the French on the right, and goes on for quite a ways.

In addition, the 4D film of the Battle was incredible – the closest any of us will ever get to the sights and sounds of the day. As you’ll see by the photo above, the design of the theatre puts you right in the middle of the action, complete with surround sound. Denise, Ian and I were the only ones in the theatre, in fact we had the whole place to ourselves. I knew we’d be seeing a 4D film, I understood this when I put the special viewing glasses on, and I anticipated the action when I took my seat. Still, I jumped a foot when the horse seemed to come charging directly at me. I think I may have even screamed a little.

Our next stop was the museum at Wellington’s Headquarters, the house Wellington returned to directly after the Battle and where he discovered his ADC Alexander Gordon laying mortally wounded. Gordon remains a touchstone of the personal losses attached to Waterloo, but there were many others who died or were horribly wounded that day, whom Wellington knew on a personal level. Waterloo cost Britain the best of its Army and exacted a toll on Wellington that will never be fully known.

From Wikipedia: “Gordon received brevet promotions to Major and Lieutenant-Colonel as a reward for carrying to London despatches announcing victory, first at the Battle of Corunna and then at Ciudad Rodrigo. After Bonaparte’s exile to Elba in 1814, Gordon was made a KCB. He was mortally wounded at Waterloo while rallying Brunswickers near La Haye Sainte, and died in Wellington’s own camp bed (above) in his headquarters during the night.

“The following is an account by John Robert Hume who was visiting the Duke of Wellington after the Battle of Waterloo –

“I came back from the field of Waterloo with Sir Alexander Gordon, whose leg I was obliged to amputate on the field late in the evening. He died rather unexpectedly in my arms about half-past three in the morning on the 19th. I was hesitating about disturbing the Duke, when Sir Charles Brooke-Vere came. He wished to take his orders about the movement of the troops. I went upstairs and tapped gently at the door, when he told me to come in. He had as usual taken off his clothes but had not washed himself.

“As I entered, he sat up in bed, his face covered in the dust and sweat of the previous day, and extended his hand to me, which I took and held in mine, whilst I told him of Gordon’s death, and of such of the casualties as had come to my knowledge. He was much affected. I felt tears dropping fast upon my hand and looking towards him, saw them chasing one another in furrows over his dusty cheeks. He brushed them suddenly away with his left hand, and said to me in a voice tremulous with emotion, “Well, thank God, I don’t know what it is to lose a battle; but certainly nothing can be more painful than to gain one with the loss of so many of one’s friends.”

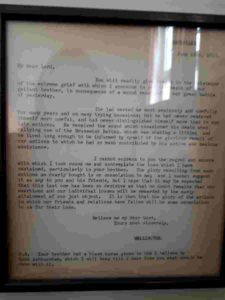

On the wall of the bedroom in which Gordon died is a typed transcript of the letter Wellington wrote to Lord Aberdeen the day after his brother’s death –

My Dear Lord,

You will readily give me credit to the existence of extreme grief with which I announce to you the death of your gallant brother, in consequence of a wound received in our great battle of yesterday.

He had served me most zealously and usefully for many years, and on many trying occasions; but he had never rendered himself more useful and had never distinguished himself more, than in our late actions.

He received the wound which occasioned his death when rallying one of the Brunswick battalions which was shaking a little; and he had lived long enough to be informed by myself of the glorious result of our actions, to which he had so much contributed by his active zealous assistance.

I cannot express to you the regret and sorrow with which I look round me, and contemplate the loss with which I have sustained, particularly in your brother. The glory resulting from such actions, so dearly bought, is no consolation to me, and I cannot suggest it as any to you and his friends; but I hope that it may be expected that this last one has been so decisive, as that no doubt remains that our exertions and our individual losses will be rewarded by the early attainment of our just object. It is then the glory of the actions in which our friends and relations have fallen will be some consolation for their loss.

— Believe me &c Wellington, Bruxelles, 19th June, 1815,

P.S. Your brother has a black horse given to him I believe by Lord Ashburgham which I will keep till I hear from you what shall be done with it.

In Part 3, we’ll continue on to the farmhouse at Hougoumont.