With this post we’re instituting Once Again Wednesdays, whereby we republish some of our most popular posts and reader favourites.

What is an Orangery? by Victoria Hinshaw – Originally published in April 2010

Since the first purposeful cultivation of plants, humankind has struggled to improve growing conditions by altering the environment. For the plant to thrive, is it too cold? Too dark? Too rainy? Too arid? Too windy? How can the plant’s living arrangements be improved to give it maximum light, water, air circulation and fertility? How can we improve on Mother Nature?

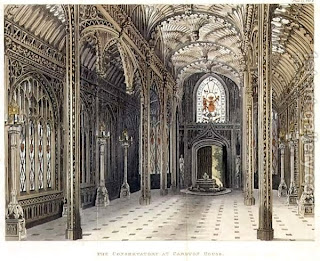

Below, inside the Orangery at Saltram House, Plymouth, Devon.

Today we take for granted the cultivation of fruits, vegetables, herbs and flowers in computer-monitored locations that bring us year-round production, the result of centuries of experimentation and invention. Two hundred years ago, our ancestors knew what was needed for maximum production, and they were quickly developing the technological requirements for success.

To some extent, the terms greenhouse, glasshouse, hothouse, orangerie, pinery, and conservatory can be used interchangeably, though each has a generally agreed upon specific meaning. All these terms and the buildings they describe existed in Georgian England, mostly at royal palaces and the estates of the wealthy aristocracy.

The Regency era, whether one confines the definition strictly to 1811-1820 or, more broadly, the French Revolution to Victoria 1789-1837, was truly a time of transition in enhanced plant cultivation indoors.

At Carlton House, the Prince of Wales’ London residence (demolished in 1826-27), a conservatory was added in 1807 in the newest construction techniques in cast iron columns and a fan vaulted ceiling supporting large glass spaces. The architect was Thomas Hopper (1776-1856) whose work was considered a tour de force. The conservatory opened into the gardens at one end. If one looked in the opposite direction, there was a clear view of the entire lower ground-floor range of rooms.

The Carlton House conservatory was intentionally theatrical, as some writers observed, bringing the term “elaborate” to a new level. The Prince Regent planned a great fete for 2,000 people on June 19, 1811, to celebrate his Regency. Down the middle of the 200-foot length of the table ran a curving stream of water lined with flowers, mossy banks and crossed by miniature bridges. Goldfish swam up and down this tiny stream. Here is the account by John Ashton in Social England Under the Regency (1895) of the Prince Regent’s conservatory and the party: “…the architecture of it is of the most delicate Gothic. …In the front of the Regent’s seat there was a circular basin of water, with an enriched Temple in the centre of it, from whence there was a meandering stream to the bottom of the table, bordered with green banks. Three or four fantastic bridges were thrown over it, one of them with a small tower upon it, which gave the little stream a picturesque appearance. It contained also a number of gold and silver fish. The excellence of design, and exquisiteness of workmanship could not be exceeded; it exhibited a grandeur beyond description; while the many and various purposes for which gold and silver materials were used were equally beautiful and superb in all their minute detail.”

Existing watercolors of the conservatory by Charles Wild (1781-1835), who painted many views of Carlton House, do not show any plants placed to take advantage of the overhead light provided by the glass and iron fan vaulting. These watercolours were published by Rudolph Ackermann in his Repositories of the Arts, beginning in October 1819. The watercolors of Carlton House and other royal residences were re-issued in 1984 by The Vendome Press, ISBN 0-86565-048-9. In Regency Design, however, Steven Parissien shows a view of the Prince Regent’s conservatory with extensive planting along the sides p. 218; also in Morley, p. 787). He also notes that the structure leaked badly and quotes Nash in 1822, “the glazed vaulting was ‘worse than useless as a roof’ and recommended replacing it with plaster.” Leaks or no leaks, Prinny’s conservatory was, as he wished, a trend-setter.

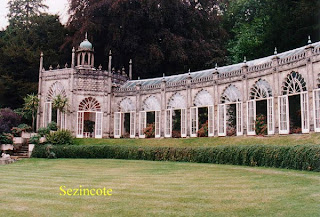

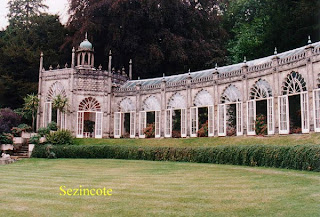

The fanciful orangery at Sezincote, in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds, inspiration for the Brighton Pavilion. Visit Sezincote.

A more modest conservatory was built by the renowned regency architect Sir John Soane at his country home Pitshanger Manor, in Ealing, a suburb of London. Mavis Batey writes, “The breakfast room opened on to a conservatory, which ran the length of the building, with sash windows to the floor, partly of coloured glass. Soane described it as ‘enriched with antique cinerary urns, sepulchral vases, statues…vines and odiferous plants; the whole producing a succession of beautiful effects, particularly when seen by moonlight, or when illuminated and the lawn enriched with company enjoying the delights of cheerful society.'” Despite the difference in scale, it is clear that the conservatories at Carlton House and Pitshanger Manor shared a common element: they were used for entertainment and socializing.

Greenhouses have ancient sources. The Romans, adept at channeling the waters and building for maximum comfort, had many schemes to enhance growing conditions for plants of all kinds. The Roman emperor Tiberius had a sort of greenhouse, called a Specularium, created with mica in small translucent flakes where we would today have glass. Tiberius, it is reported, needed a year-round supply of his favorite food: cucumbers! Further developments in specularia included ducts carrying hot water or cool air, typical of Roman engineering. Among the plants grown in these mica-roofed structures were grapes, peaches and roses.

Orangeries can be seen at many English country houses and on the grounds of several royal palaces im Britain, as well as throughout Europe. Below, the orangery at Belton House, Lincolnshire

A primary motivation for the improvement of greenhouse design was the English penchant for the collection and study of botanic material from all over the globe. The earliest explorers brought back seeds and exotic species. The damp, chill English climate needed some alteration if these new species were to survive and flourish.

Kew Gardens (officially the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew) originally belonged to the royal family. Frederick, Prince of Wales, (son of George II and father of George III) and his wife, Princess Augusta, had a great interest in exotic plants. Their collection is the core of today’s 40,000 varieties of plants at Kew. None of Kew’s hothouses survive from the Georgian period. One regency-era building, the Nash Conservatory, was built at Buckingham Palace in the design of a Greek temple; it was moved to Kew in 1836. Recently fully restored, the Nash Conservatory is used now as a school education center.

By the middle of the 19th century, the popularity of greenhouses had grown exponentially. What’s more, materials became less expensive and more readily available, so greenhouses and growing plants under glass were no longer a pastime only of the wealthy. Small greenhouses and conservatories of many designs were added to middle class Victorian houses. There was also competition by cities and countries to build conservatories as part of grand public parks. These housed exotic, non-native plants as well as common varieties, and remain popular today.

One of the most famous glass buildings in the world was the Crystal Palace, built in London in 1850-51 for the Great Exhibition. Chief architect was Joseph Paxton (1803-65), former gardener to the sixth Duke of Devonshire (the Bachelor Duke). It contained all kinds of exhibits, not only plants. Nonetheless, the design of the Crystal Palace influenced decades worth of greenhouses and conservatories, including the many you can order for your home today.

For her help in finding some interesting sources on this subject, special thanks to Jo Manning.

Among the sources used for this post are:

Batey, Mavis, Regency Gardens, Shire Garden History, 1995, ISBN 0-7478-0289-0.

Hobhouse, Penelope, Gardening Through the Ages, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992, ISBN 0-671-72887-3.

Parissien, Steven, Regency Style, Washington, D. C.: The Preservation Press, 1992, ISBN 0-89133-172-7

Rogers, Elizabeth Barlow, Landscape Design: A Cultural and Architectural History, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 2001, ISBN 0-8109-4253-4.