In a prior post in our gardening series we met nurseryman Mr. John Lee, who took up operation of the Hammersmith nursery garden upon his fathr’s death. Mr. Lee followed in father’s foot steps as far as the accumulation of new and rare plants was concerned, as well. He and the Empress Josephine of France, pictured above, in partnership, sent Francis Masson to the Cape of Good Hope in order to gather botanical samples in the hopes of introducing the beautiful flowers of that region to European gardens. In this connection it may be of interest to note that a large portion of Masson’s Herbarium is preserved in the collections of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

Additionally, the Empress became patroness to James Niven, who worked in the Botanic Garden at Penicuick in Scotland and travelled to the Cape of Good Hope in 1798 to collect seeds, where he stayed until 1803. During his second visit between 1805 – 1812, he collected seeds for Empress Josephine, and embarked on a journey through the districts of Malmesbury, Piquetberg and Kamiesberg where he collected rare species of Protea. He returned home with a considerable herbarium, including a set of Erica specimens which found its home in the Botancial Garden in Edinburgh.

Joséphine de Beauharnais (23 June 1763 – 29 May 1814) was the first wife of Napoléon Bonaparte, and thus the first Empress of the French. Her first husband Alexandre de Beauharnais had been guillotined during the Reign of Terror, and she had been imprisoned in the Carmes prison until her release five days after Alexandre’s execution.

Josephine was born at the family’s sugar plantation on the French Caribbean island of Martinique and it’s slow pace of life she dubbed “nonchalance.” It was there, in a lush tropical atmosphere, that Josephine developed her passion for flowers and gardening. Later she would introduce flower gardening to France, particularly at Malmaison. So avid a cultivator and gardener was the Empress that we still have plants that are named in her honor.

When Josephine first purchased the property in April of 1799, Malmaison was a run-down estate, eight miles west of central Paris that encompassed nearly 150 acres of woods and meadows. Napoleon was incredulous when Josephine first bought Malmaison at an inflated price and then proceeded to fund it’s renovations. After her divorce from Napoléon, Joséphine received Malmaison in her own right, along with a pension of 5 million francs a year, and remained there until her death in 1814. The gardens housed West Indian plants and is known as the birthplace of the tea rose. In fact, they housed over 250 varieties of roses from across the world, 170 of which were famously painted by Pierre-Joseph Redoute – prints of which remain favorites today, such as the one at right.

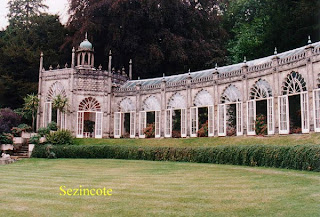

The aim of the Empress Joséphine was to transform her large estate into “the most beautiful and curious garden in Europe, a model of good cultivation”. And a model of modern gardening Malmaison became. Amongst other innovations, Josephine had installed a heated orangery large enough for 300 pineapple plants, a greenhouse, heated by a dozen coal-burning stoves. Architects Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine initially enclosed the park and built stables and hot houses. The garden was subsequently remodelled by landscape architect Louis Martin Berthault.

Most importantly in gardening history, the Empress introduced nearly 200 new species of plants to France, including dahlias from Mexico, and encouraged her gardeners to create new species of roses. Her principal source for roses was the Lee & Kennedy Vineyard Nursery in London, of which the Mr. Lee mentioned above was co-owner. Josephine wanted every rose known in the world, and in 1804, by way of Lewis Kennedy, she was in proud possession of the new Chinese roses: Slater’s Crimson China, Parson’s Pink and Hume’s Blush Tea Scented China. These everblooming roses were recent imports to England from China, and it was a coup for the Empress (and for France) to have them growing at Malmaison. They became known as stud roses, potent parents of the modern everblooming rose cultivars.

The most famous rose, and a perennial favorite, to be named for Josephine is the Souvenir de la Malmaison, a Bourbon, shown at rght.

According to Clair G. Martin III, the Ruth B. and E. L. Shannon Curator of the Rose Garden at the Huntingdon Library, “At the height of the war in the early 1800s, Napoléon was sending money to England to pay his wife’s plant bills, and the British Admiralty was allowing ships to pass through its naval blockades to deliver new types of roses to Malmaison.” Joséphine’s influence was felt across the channel, as well, as many British aristocrats joined the frenzied competition for the newest blooms.”

Josephine commissioned a book about the garden and its plants that was completed t

hree years after her death and published under the title “Jardin de Malmaison-Description des Plantes Rares Cultivees a Malmaison et a Navarre” with text by renowned French botanist Etienne-Pierre Vententat. The book contained 175 watercolors by Redoute and originally appeared in installments.

When I was in Paris recently, I thought to visit Malmaison and the gardens there until I learned that, sadly, the garden today is limited to a very small area with nothing to speak of remaining of Empress Josephine’s efforts or botanical collections.

To learn more about the history of the gardens at Malmaison, read Jardin De La Malmaison: Empress Josephine’s Garden with an essay by Marina Heilmeyer by H. Walter Lack.