The most famous name associated with Blenheim in modern times is Winston Spencer Churchill, grandson of the seventh duke. He was born at Blenheim in 1874, son of Randolph Churchill (a second son) and his American wife, Jennie Jerome.

Jennie was staying at Blenheim when she went into labor and the baby arrived, typical of his later impatience, two weeks before his due date. Winston proposed to Clementine Hozier in the Blenheim garden folly known as the Temple of Diana.

Sir Winston and Lady Churchill are buried in the graveyard of St. Martin’s Church in the nearby village of Bladon.

Sir Winston and Lady Churchill are buried in the graveyard of St. Martin’s Church in the nearby village of Bladon.As an archetypical English country house, Blenheim today is a museum of art and historical memorabilia, featuring such attractions as the victory dispatch the first duke wrote to Sarah on a restaurant menu, elaborate tapestries depicting his campaigns, ducal coronation robes, and the memorabilia of three centuries.

The gardens at Blenheim have been redesigned many times and currently reflect a variety of styles from formal, at left, to the rolling hills of Capability Brown’s tastes.

In the long library, there is a chart of the family’s genealogy, a familiar object in most English Stately Homes. However, instead of just showing the family’s lineage back to William the Conqueror, this Spencer-Churchill (Marlborough) family traces its origins to Charlemagne.

Below, see the long library set up for a wedding.

Blenheim is one of many stately homes which can be rented for a lavish ceremony and reception.

As I mentioned in my first post on Blenheim, it is not a house designed for a family to live in. Wandering through the remarkable but sadly bleak trappings of Blenheim, one is struck by how much the first Duke of Wellington learned from Blenheim’s dominion over the entire Marlborough family. When offered a great Waterloo Palace as a gift from the nation after his victory over Napoleon (much as the first duke of Marlborough had been promised a great estate after his victory at Blenheim), Wellington proceeded cautiously. The Iron Duke knew what a burden Blenheim had been to its owners. What Wellington did, the story of Stratfield Saye, we will save for another blog post.

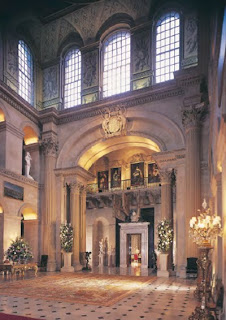

The Great Hall is 67 feet high with stone carvings by Grinling Gibbons. The arms on the stone arch are those of Queen Anne. The ceiling, painted in 1716 by Sir James Thornhill, shows the Duke of Marlborough kneeling to Britannia.

The Great Hall is 67 feet high with stone carvings by Grinling Gibbons. The arms on the stone arch are those of Queen Anne. The ceiling, painted in 1716 by Sir James Thornhill, shows the Duke of Marlborough kneeling to Britannia.

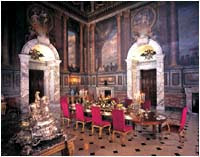

The Saloon is also known as the state dining room and is now used by the family once a year on Christmas Day. The magnificent ceiling was painted by Louis Laguerre. Various nations are represented in wall paintings, whilst the ceiling shows the 1st Duke in victorious progress but stayed by the hand of peace.

Another view of the saloon.

In the Green Writing Room, below, the Blenheim tapestry depicts the first Duke of Marlborough accepting the surrender of the enemy in 1704, the accomplishment for which he was honored with the dukedom and the estate.

A detail of the Battle of Blenheim tapestry.