Louisa Cornell

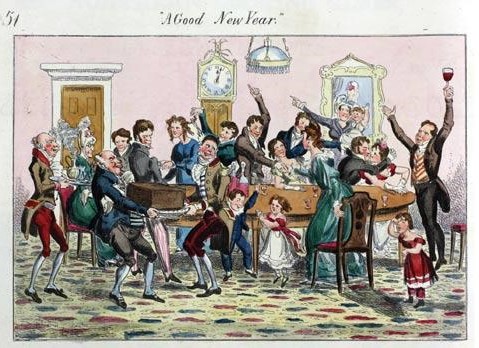

As the Christmas celebrations slow down, Scots gear up for Hogmanay, the celebration of New Year’s Eve. A Scots word of uncertain heritage, Hogmanay (pronounced, roughly, HUG-ma-nay) might come from ancient Greek (“holy month”), French (“the new year”), or Gaelic, or Norse, or… Whatever etymological theory you subscribe to, the holiday itself is all Scottish! The age-old traditions associated with Hogmanay have been recorded at least since the 16th century and hold firm to this day.

The earliest modern era accounts record it as a Scottish custom as noted by Chamber’s 1856 Book of Days :

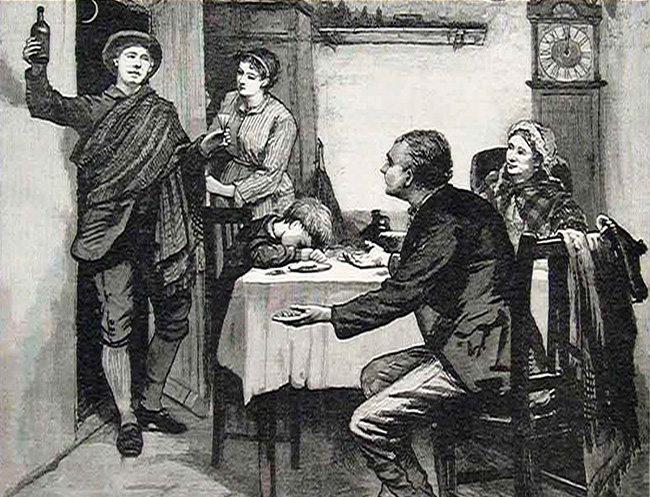

“There was in Scotland a first footing independent of the hot pint. It was a time for some youthful friend of the family to steal to the door, in the hope of meeting there the young maiden of his fancy, and obtaining the privilege of a kiss, as her first-foot. Great was the disappointment on his part, and great the joking among the family, if through accident or plan, some half-withered aunt or ancient grand-dame came to receive him instead of the blooming Jenny.”

The part of the ritual that is far older than that, which makes it one of the oldest and most intriguing traditions for a New Year’s Eve in Scotland is the tradition of the First Footer. “The First Footer” is a Scottish New Year’s tradition where the first person to cross the threshold after midnight on New Year’s Eve is considered to bring luck for the new year. The ideal “first footer” was and remains a tall, dark-haired man. This preference for dark hair is believed to stem from the days of Viking invasions when a blonde stranger would be seen as a threat. According to tradition, the first footer should never be a woman, why has been lost to the mists of time.

The first footer usually brings gifts like a lump of coal or some peat (representing warmth), salt (representing health), shortbread (a traditional Scottish biscuit) or black bun (representing flavor,) and a dram of whisky (representing good cheer).

Black bun is a type of rich fruit cake completely covered with pastry. It was originally eaten on Twelfth Night in Scotland but is now more associated with Hogmanay. Here is a recipe should you want to add Black Bun to your New Year’s Eve traditions!

Auntie Lesley’s Black Bun Recipe

Ingredients

Pastry Case

- 110 grams butter

- 220 grams plain flour

- Pinch of salt

- ½ teaspoon baking powder

- Cold water

- 1 egg, beaten

Filling

- 170g plain flour

- One level teaspoon ground allspice

- ½ level teaspoon each of ground ginger, ground cinnamon,30 grams chopped mixed peel

- ½ level teaspoon baking powder

- ½ level teaspoon cream of tartare

- Pinch of salt

- Soaked fruit mixture: 450 grams seedless raisins, 450 grams currants, 60 grams chopped almonds, one tablespoon brandy – mixed together and left to soak overnight

- 110 grams soft brown sugar

- 30 grams chopped mixed peel

- Generous pinch of black pepper

- One large egg (beaten)

- Milk to moisten (approx ¼ pint)

Method

1. Grease a loaf tin. Rub butter into flour, salt and baking powder, mixing in cold water to make a stiff dough.

2. Roll out pastry and cut into five pieces, using bottom, top and sides of the tin as a rough guide.

3. Press the bottom and four side pieces of pastry into the tin, pressing overlaps to seal the pastry shell.

4. Sift flour and spices, baking powder, cream of tartare and salt. Bind together with soaked fruit mixture and sugar, mixed peel, pepper, egg and milk.

5. Pack filling into the pastry-lined tin and add pastry lid, pinching edges and using egg to seal well. Lightly prick surface with a fork and make four holes in the bottom layer of pastry using a skewer. Depress the centre slightly (pastry lid will rise as it cooks).

6. Brush top of pastry case with beaten egg to glaze.

7. Bake in pre-heated oven at 325OF/160OC/Gas Mark 3 for 2½ to 3 hours, until a skewer comes out clean.

As you can see, people in Scotland knew how to celebrate the New Year in grand style as well!

As for today, I will confess I would love to celebrate Hogmanay at least once in Scotland from the First Footer to the Black Bun to the singing of Auld Lang Syne. Until then, Kristine, Victoria, and I wish each and every one of you a very Happy New Year and may all your first footers be dark-haired and bring you much good luck!

AULD LANG SYNE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9lht2mRd2kQ