by Regan Walker

Echo in the Wind, my new Georgian romance set in 1784, smuggling features prominently. Tea drinking was so popular that many people turned a blind eye to the activities of the smuggling gangs. Because it was an illegal trade, it is impossible to know exactly how much tea was smuggled into Britain during the years of high taxation in the eighteenth century, but it is clear that while tea drinking was becoming ever more popular and widespread, the official imports of tea were not increasing. By the 1780s, in areas where the smugglers operated most freely, virtually all the tea consumed was smuggled.

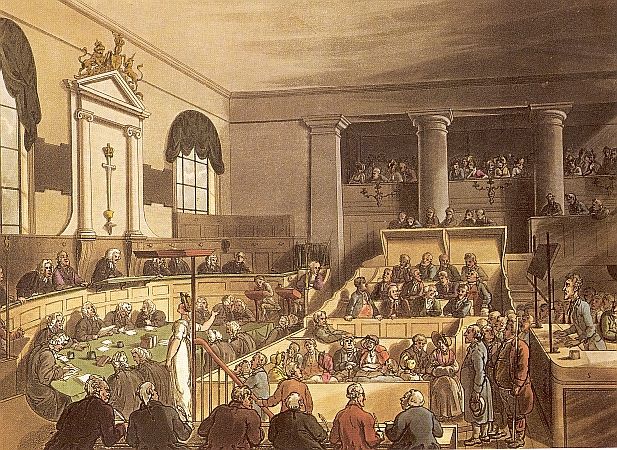

Echo in the Wind includes a smuggling trial at the Old Bailey. To portray the trial accurately, I dove into the Old Bailey archives. (Yes, the trials are available in an online database: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/.)

How smuggling cases were portrayed:

Before the 1770s, England’s government portrayed smuggling as a crime against the nation, but after this time, smuggling became a crime of assault against revenue officers. During the first part of the eighteenth century, smugglers might refer to their trade in terms of tradition. They were surprised to find they awaited execution for such a commonplace activity. But after the 1770s, smugglers increasingly considered smuggled goods to be their private property. To them, the revenue officers were wrong for seizing what was not theirs by right.

Some of that can be seen in the trial scene in my story. To capture the trial as it might have occurred, I scanned dozens of transcripts of Old Bailey trials. In the end, I selected the trial of John Shelley for my model. He was accused of disturbing the peace, assaulting “officers of the king” and failing to pay duties on imported tea, otherwise known as “unaccustomed goods”.

Since my heroine, Lady Joanna West, is the “master of the beach” for a gang of smugglers operating off the West Sussex coast, she listens carefully as the trial begins:

With a word from the judge, a clerk at the end of the counsel table stood and began to read from a paper.

“The prisoner, one John Shelley, is accused of disturbing of the peace of our Lord the King on the nineteenth of November last. With firearms and other weapons, including bludgeons, a blunderbuss, a pistol and a sword called a cutlass, he did unlawfully, riotously and feloniously assault officers of the king. He and ten other persons took away three hundred pounds weight of tea, being unaccustomed goods liable to pay duties, and which duties had not been paid.”

“A smuggling case!” Cornelia exclaimed in a whisper to Joanna. At the mention of “unaccustomed goods” Joanna had known the nature of the case they were to hear. Her stomach was already tied in knots at the thought of what lay ahead.

The clerk paused and then began again. “The prisoner is charged with another count for forcibly assaulting, hindering, obstructing and opposing said officers.”

Looking up from the paper he held, he asked the accused, “How do you plead?”

The man responded from where he cowered behind the wooden railing. “Not guilty.” By the look on his face, Mr. Shelley well understood he faced the possibility of execution.

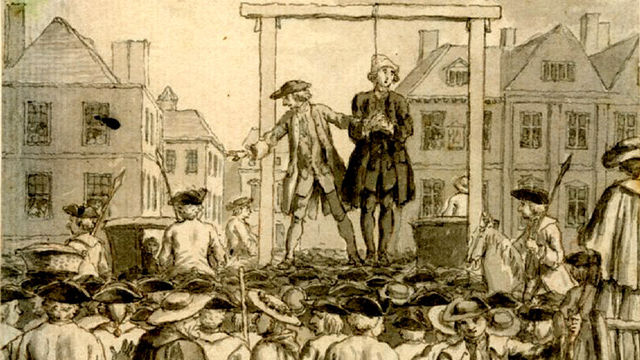

As a lawyer, I found the transcripts from the Old Bailey trials fascinating. As a writer, I recognized them as having the potential to add realistic drama to my story, adding to the heroine’s fear of ending up on the gallows.

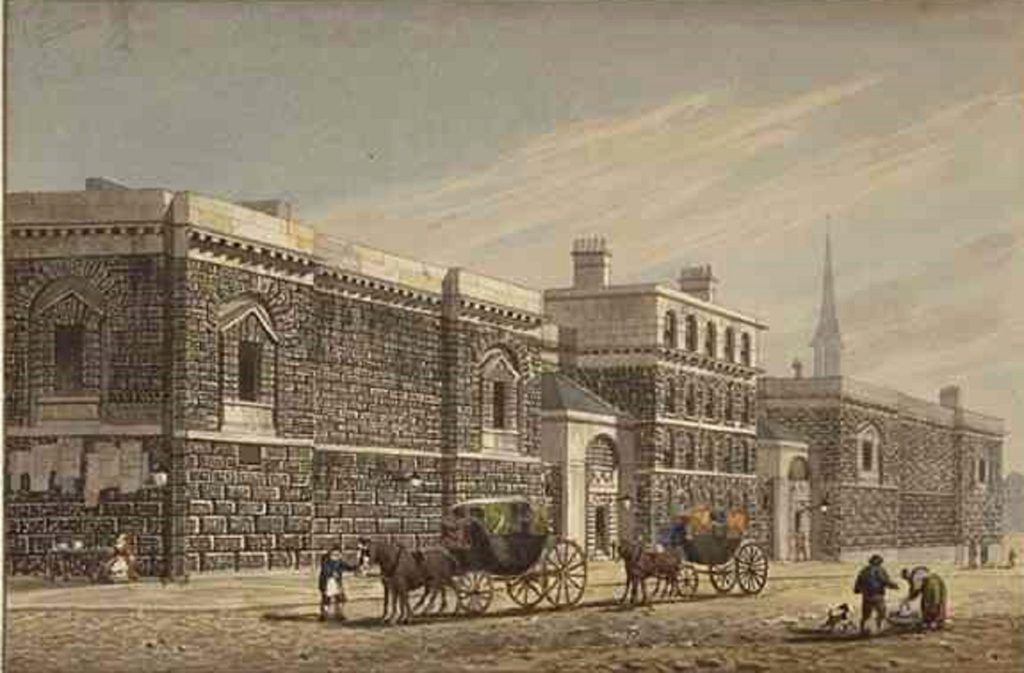

The Old Bailey:

By the time of my story, the Old Bailey had long been the place where criminals were tried. Between 1674 and 1834, over 100,000 criminal trials were carried out at the Old Bailey. In the late 18th century, the Old Bailey was a small court adjacent to Newgate gaol. Hangings were a public spectacle in the street outside the Old Bailey until May 1868

The result of the trials:

The majority of smugglers tried at the Old Bailey before 1787 had been charged with the capital offenses of armed assembly or carrying illicit goods. But this was to change. Between 1787 and 1814, 49 out of 64 smuggling cases featured assault and/or obstruction as the main charges.

Throughout the eighteenth century, the acquittal rate was seldom less than 25 per cent, and often more than 50 per cent of those indicted. As the century progressed, the conviction rate fell well below 25 per cent. In 1784, the year of my story, the conviction rate was only 14% (out of 1037 indictments, there were only 149 convictions).

A letter in the Morning Chronicle for 1 January 1773 complained, “The numerous acquittals at the Old Bailey, on some days greater than the convictions, are truly alarming.” They further observed, “Whenever any case admits of the least doubt, the Judge and Jury give it a cast in favour of life and liberty.”

It is no surprise that during the 1780s and later, communities were more frequently the smugglers’ willing accomplices than their terrorized victims. Then, too, the rule of law posed formidable problems for the prosecutors. The law was slow and costly, and biased judges and juries often failed to convict on the most straightforward evidence. Bribery produced many false alibis and witnesses “disappeared” or had convenient lapses of memory.

And what of Mr. Shelley?

At the end of the trial in my story, Mr. Shelley is found guilty in one of those rare instances of conviction. Of course, this causes Lady Joanna much fear. After some upheaval in the court and much sobbing by the man’s relations, this is how the scene ends:

The prisoner was led away and the gallery began to empty. The women who had watched the trial beside them were dabbing at their eyes with handkerchiefs as they stood to leave.

Once they were gone, Cornelia abruptly stood. “Tea, I think, is in order. Twinings?”

Joanna got to her feet, her shoulders sagging with the weight of what she had witnessed. “Some refreshment after that is welcome, though I shouldn’t wonder if we ought to drink something stronger than tea.” Particularly if it were tea she knew might very well be smuggled. But then, so was most of England’s brandy.

ECHO IN THE WIND

“Walker sweeps you away to a time and place you’ll NEVER want to leave!”

~ NY Times Bestselling author Danelle Harmon

England and France 1784

Cast out by his noble father for marrying the woman he loved, Jean Donet took to the sea, becoming a smuggler, delivering French brandy and tea to the south coast of England. When his young wife died, he nearly lost his sanity. In time, he became a pirate and then a privateer, vowing to never again risk his heart.

As Donet’s wealth grew, so grew his fame as a daring ship’s captain, the terror of the English Channel in the American War. When his father and older brother die in a carriage accident in France, Jean becomes the comte de Saintonge, a title he never wanted.

Lady Joanna West cares little for London Society, which considers her its darling. Marriage in the ton is either dull or disastrous. She wants no part of it. To help the poor in Sussex, she joins in their smuggling. Now she is the master of the beach, risking her reputation and her life. One night off the coast of Bognor, Joanna encounters the menacing captain of a smuggling ship, never realizing he is the mysterious comte de Saintonge.

Can Donet resist the English vixen who entices him as no other woman? Will Lady Joanna risk all for an uncertain chance at love in the arms of the dashing Jean Donet?

Echo in the Wind on Amazon:

US: http://ow.ly/jBtZ30bQ5km UK: http://ow.ly/DD3A30bSamm

Regan’s website: http://www.reganwalkerauthor.com/

The Pinterest storyboard for Echo in the Wind: https://www.pinterest.com/reganwalker123/echo-in-the-wind-by-regan-walker/