By Guest Blogger Jo Manning

This sumptuous accompaniment – replete with gorgeous full-color and some black and white images — to the exhibition currently showing at The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich (until April 17th) comprises essays by Quintin Colville; Vic Gatrell; Christine Riding; Jason M. Kelly; Gillian Russell; Margarette Lincoln; Hannah Greig; and Kate Williams on different aspects of the controversial Emma Hamilton’s life, legend, and times.

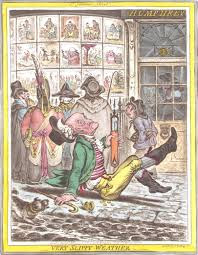

I’ve been to two previous art shows that featured Emma Hamilton and other Georgian celebrities: Joshua Reynolds And The Creation of Celebrity (at the Tate Britain in 2005), and the George Romney exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery in 2002. Both were exemplary, dedicated to these superb portraitists and their famous subjects. These sitters became instant celebrities owing to the prints of the portraits becoming widely disseminated. (These prints generated a bit of nice income for the painters, as well.) The caricaturist Gillray illustrated the popularity of these prints in his well-known “Very Slippy Weather,”showing Londoners entranced by the latest prints for sale at stationers’ shops.

Emma Hamilton (born 1765-died 1815) was also variously known as Amy/Amey/Emy/Emily Lyon and Emma Hart until she married Sir William Hamilton, British envoy (ambassador) to the Court of Naples, thus becoming Lady Hamilton. She was one of the most controversial – and, yes, notorious — women of her time. Much has been written about her but there remains a good deal of speculation, as well. (Among the best-written biographies and novels of her, in my opinion, are these: Williams, Kate, England’s Mistress: The Infamous Life of Emma Hamilton, 2006; Fraser, Flora, Beloved Emma: The Life of Emma, Lady Hamilton, 2004; and Susan Sontag, The Volcano Lover: A Romance, 1992.)

For starters, she was an unqualified beauty: a perfect oval of a face; thick, wavy, cascading auburn tresses; big-eyed; a rosebud mouth; and a complexion described by one besotted writer as a “velvet skin of lilies and roses”. Surprisingly tall, with good, square shoulders and a substantial bosom, she defied the “pocket Venus” model prized by prevailing18th century aesthetic standards. A killer combination, this, that pouting baby face and a curvy, womanly figure. Who would not want to paint her? More to the point, who would not want to be her lover?

|

|

Emma Hart as a Bacchante, circa 1785

|

Biographies and other writings on Emma find more ample material in the second and last third of her life than in the first. Yes, she grew up poor; yes, she worked in menial positions as a young teen; yes, she moved to London at one point; yes, men began to notice her. What is uncertain is when and how she became a sex worker. Did her mother actually pimp her out at the age of fourteen? Did she work the streets or was she in a brothel? At any rate, we are on more solid ground when she is taken up by Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh (this name is pronounced “Fanshawe”), a wealthy, dissolute rake who nonetheless has her take up the ladylike sport of horse-riding (“To hounds!”) and teaches her more genteel manners. (She was said to have a vulgar speaking voice and bad diction; her spelling, from letters that remain, show her bad spelling, but many people then were bad spellers.)

He dumps her, however, when she becomes pregnant. She is about sixteen when she is sent away – and the record is not clear whether or not this child was Fetherstonhaugh’s or Greville’s or another man in their set, Jack Payne — and gives birth to a girl, said to be named Emma Carew. (She was also known as Emma Hartley; after years as a teacher/governess she died alone in Florence and is buried in the English Cemetery. It appears she’d had a sad life.)

After giving birth, she left the child to be raised by a relative in the country and took up with this man in Fetherstonhaugh’s set, Charles Greville, who refused to have another to do with the baby and further set about further “improving” Emma in manners, diction, et cetera. Greville,

who was the nephew of the very wealthy Lord Hamilton, but not well-off himself, was a bit of a control freak, from all I have read about him and which these essays confirm. It was Greville who introduced her to the portrait painter George Romney….and thereby hangs quite a tale. And here is Romney looking his moodiest, in an unfinished self-portrait (circa 1781/2):

who was the nephew of the very wealthy Lord Hamilton, but not well-off himself, was a bit of a control freak, from all I have read about him and which these essays confirm. It was Greville who introduced her to the portrait painter George Romney….and thereby hangs quite a tale. And here is Romney looking his moodiest, in an unfinished self-portrait (circa 1781/2):

I myself have researched and written about Romney’s obsession with Emma, whom he painted at least sixty times and sketched many more times. At his death, notebooks were found filled with drawings – many unfinished — of his muse Emma Hart – as she was then known. Romney was a strange old cuss. Extremely talented – he became one of the most renowned portraitists in England – but he was prone to serious bouts of depression (it apparently ran in his family). He was a very moody man. Emma Hart enriched his life, and when she was gone from it, he went even more downhill mentally.

|

|

Emma Hart In A Straw Hat

|

The only quibble I have with the uniformly excellent essays making up this book is in the Christine Riding piece. Emma Hart sat for George Romney some nine years. Nowhere in all the background reading and research I did for my guest blog for Number One London did I find any evidence that there was anyone else in that studio save Romney and Emma. I never saw mention of a “chaperone” nor of any friends/acquaintances of Greville or Emma dropping in. And this is telling, because sittings for artists were social occasions; observers sat and gossiped and were served tea, etc. This was the norm. One sitting could take up to an hour; these sittings were longer. Again, never, ever, did I find any of this normal way of conducting sittings followed by Romney with Emma. Greville, to my knowledge, simply would not allow this.

|

|

Emma Hart as Circe, painted by George Romney c1782… Exquisite!

|

Charles Greville was an extremely jealous and controlling man, possessive to a rather sickening degree, in my opinion. Emma Hart was his possession; he did not want to share her with anyone, even in the benign setting of sitting for a portrait. All I read led me to believe that those two, artist and subject, were alone…together. For NINE years! And I wondered, did they become lovers? It’s tantalizing to imagine this, but there is no solid proof. What seems to be evident, however, is that Emma opened up to Romney as she was posing and entertained him by singing and dancing and having fun. (I reckon she did not have much fun in her relationship with Greville, given his rigid personality.)

And, although over the years people have made fun of Emma and her “Attitudes” – i.e., the dramatic poses she struck to entertain guests – there needs to be, I think, an objective re-examination of her talents, both with these poses and with her singing. (She did hang out with theatre people when she was younger and may even have appeared onstage.) Apparently she wasn’t as untalented as so many reported over the years. I found that re-appraisal fascinating…and it confirmed to me that so much of what was written at the time and subsequently thereafter – much of it simply repeating the same anecdotes — was not to be trusted. (I found this to be true when I was writing the biography of Grace Dalrymple Elliott, My Lady Scandalous. There is a lot of misinformation/misinterpretation out there and one has to be cautious.)

|

|

Perhaps my favorite portrait of Emma Hart by George Romney

|

When Emma Hart was given to Lord Hamilton by his nephew (yes, she was a gift, as she was, after all, his possession), she was eagerly received. Greville was reportedly tired of her and, assiduously searching for a wealthy woman to marry, Emma was in his way. By sending her to Naples on a ruse (oh, yeah, go on ahead, I’ll be joining you directly!), he accomplished his purpose. The much older, lonely man, besotted by her beauty, took her in and eventually proposed marriage to her. (She was 21 when Greville rid himself of her; Hamilton was about 56. They married when Hamilton was 61 years old; his first wife, an heiress, had died before Emma appeared on the scene and he’d been alone for some years.)

Most of you may know the rest of this celebrated story. Emma – now Lady Hamilton and ensconced in luxury far beyond her imagination whe

n she was walking the London streets and/or working in a brothel – met Lord Nelson, the famed British admiral and hero of Trafalgar, and Lord Hamilton – bless his heart – was toast.

n she was walking the London streets and/or working in a brothel – met Lord Nelson, the famed British admiral and hero of Trafalgar, and Lord Hamilton – bless his heart – was toast.

The details can be found in the essays, but a last word about Emma’s child(ren) with Nelson is perhaps appropriate here. She had Horatia, who lived to a ripe old age, the wife of a minister and the mother of a slew of children, whose maternity Emma never acknowledged publicly, and possibly one or two other children, one of whom was said to have died very young or at birth. One or two sources I read in my research implied that there were twin girls, one of whom was sent to an orphanage, the other having died or disappeared. Sadly, it did not appear that Emma was much of a mother (though some sources said she was close to Emma Carew, her first daughter), but there is not much to go on to substantiate what happened to these later, mysterious twins…if they indeed ever existed at all, poor lost babes.

|

|

Lord Nelson, Hero of the Battle of the Nile and of Trafalgar

|

This is quite a wonderful compilation with superb illustrations, fast reading, and an excellent introduction to the life and loves of a singular woman. Enjoy the reading and perhaps shed a tear or two for Emma Hamilton’s last tawdry years. So many women like her wound up in France, dying there, forgotten. (My biography subject died there, as did the actress mistress of King William IV, Dorothy Jordan, along with other discarded women.) Nelson wanted Emma taken care of by the country he’d served so well; well, she wasn’t.

And, if you can, visit the exhibit at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London before it closes. As you can tell from the few sample images here, it is a feast for the eyes.

Quinton Colville’s introductory essay, “Re-imagining Emma Hamilton,” gives an excellent overview of the mythology and reality surrounding this woman; he is the Curator of Naval History at the National Maritime Museum in London. There are six full and informative articles in this companion to the exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, starting with historian Vic Gattrell, who teaches at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge; his essay is “Sexual Exploitation And The Lure Of London,” a subject on which he has written extensively. Christine Riding holds the position of Head of Arts and Curator of the Queen’s House at the National Maritime Museum; she was previously at the Tate Britain, where she curated 18th and 19thcentury British art; her essay is “Romney’s Muse: A Creative Partnership In Portraiture”.

Jason M. Kelly takes us to the middle part of Emma Hamilton’s career, to Naples, where, as the wife of the British ambassador, she moves in very different circles and we take a look at “A Classical Education: Naples And The Heart of European Culture.” Kelly is an associate professor at Indiana University-Purdue and directs the Arts and Humanities Institute there. Gillian Russell penned “International Celebrity: An Artist On Her Own Terms”; Russell writes on fashionable women and on theatre in Georgian London.

Rounding out these essays are Margarette Lincoln (“Emma And Nelson: Icon And Mistress Of The Nation’s Hero” and Hannah Grieg on Emma’s last sad years with “Decline And Fall: Social Insecurity And Financial Ruin.” ) Lincoln is a specialist in English naval history and served as Deputy Director of the National Maritime Museum for several years; she is now a visiting professor at the University of London. Grieg is an academic who is now at the University of York, lecturing on 18thcentury British social, cultural, and political history; much of her research centers on the lives of the elite class in that society.

A special treat at the end of this fascinating book is biographer Kate Williams’ take on “Emma Hamilton In Fiction And Film.” Williams is a professor of history at the University of Reading and author of England’s Mistress.

|

|

Poster for Vivien Leigh/Laurence Oliver biopic That Hamilton Woman!

|

EMMA HAMILTON: SEDUCTION & CELEBRITY, edited by Quintin Colville with Kate Williams, Thames & Hudson/Royal Museums Greenwich, 2016, 280 pages

Oooh! I have been coveting this book since I found out about the exhibit! Now I have no choice! Have to have it! I so wish I could see the exhibit! Then, as today, a great deal of information about celebrities needs to be take with a grain of salt until investigated. And, I fear, the truth is always somewhere in the middle of it all! Thanks so much, Jo, for a fabulous review!

My pleasure, Louisa! It is an excellent source and the contributors write well about those times 🙂