From Memoranda; or, Chronicles of the Foundling Hospital by John Brownlow (1847)

“. . . . the difficulty which presented itself paramount to all others, related to the manner in which so great a number of children was to be reared. In the first year of this indiscriminate admission, the number received was 3,296; in the second year, 4,085; in the third, 4,229; and during less than ten months of the fourth year (after which the system of indiscriminate reception was abolished), 3,324. Thus, in this short period, no less than 14,934 infants were cast on the compassionate protection of the public! It necessarily became a question how the lives of this army of infants could be best preserved; and the Governors, not being able to settle this point among themselves, addressed certain queries to the College of Physicians, which were promptly answered, by recommending a course of treatment consonant to nature and common sense! Children, deprived as these were of their natural aliment, required more than usual watchfulness; and although, on a small scale, the providing a given number of healthy wet-nurses, as substitutes for the mothers of infants, would have been an easy task, yet, when they arrived in numbers so considerable, the Governors found that the object they had in view must necessarily fail from its very magnitude.

“It has been truly said, that the frail tenure by which an infant holds its life, will not allow of a remitted attention even for a few hours: who, therefore, will be surprised, after hearing under what circumstances most of these poor children were left at the Hospital gate, that, instead of being a protection to the living, the institution became, as it were, a charnel-house for the dead! It is a notorious fact, that many of the infants received at the gate, did not live to be carried into the wards of the building; and from the impossibility of procuring a sufficient number of proper nurses, the emaciated and diseased state in which many of these children were brought to the Hospital, and the malconduct of some of those to whose care they were committed (notwithstanding these nurses were under the superintendence of certain ladies—sisters of charity), the deaths amongst them were so frequent, that of the 14,934 received, only 4,400 lived to be apprenticed out, being a mortality of more than seventy per cent.”

|

| James II shilling copyright icollector.com |

Charles Knight writes more on this theme in Knight’s Cyclopædia of London (1851) –

“Of 14,934 children received under the new system, only 4400 lived to be apprenticed! On the 8th of February, 1760, a resolution was passed in Parliament, declaring “That the indiscriminate admission of all children under a certain age into the Hospital had been attended with many evil consequences, and that it be discontinued.” From 1756 to 1771, the years of the Parliamentary connection, the national fuuds coutributed, it appears, no less a sum than 549,796. 16s. to the expenses of this illjudged experiment. Yet it was not till 1801 that the most objectionable practice of taking children without inquiry, on a payment of £100, was formally abolished.

Now Knight touches upon a theme that is relevant to the Foundling Museum’s current online exhibition, Threads of Feeling.

“Tokens.—It will be seen, that one of the regulations at the outset was, that persons leaving children should “affix on them some particular writing, or other distinguishing mark or token.” Forty years ago, the Governors being curiously inclined, appointed a committee to inspect these tokens, with the view of ascertaining their general nature, which committee, having examined a portion of them, reported the following to be specimens of the whole: viz.—

A half-crown, of the reign of Queen Anne, with hair.

An old silk purse.

A silver fourpence and an ivory fish.

A stone cross, set in silver.

A shilling, of the reign of James the Second.

A silver fourpence of William and Mary, and a silver penny of King James.

A silver fourpence.

A small gold locket.

A silver coin (foreign), of sixpence value.

“In 1757, a lottery ticket was given in with a child, but whether it turned up a prize or a blank is not recorded. The following lines were pinned to the clothes of one of the deserted infants :—

“Go, gentle babe, thy future life be spent

In virtuous purity and calm content;

Life’s sunshine bless thee, and no anxious care

Sit on thy brow, and draw the falling tear;

Thy country’s grateful servant may’st thou prove,

And all thy life be happiness and love.”

“Another child, received on the first day of admission, had the following doggrel lines affixed to its clothes:—

“Pray use me well, and you shall find

My father will not prove unkind

Unto that nurse who’s my protector,

Because he is a benefactor.”

|

| copyright Needleprint |

“At this period, the station in life of the parties availing themselves of the charity, could only be surmised by the quality of the garments in which the children were dressed, the particulars of which were faithfully recorded; the following being a sample, viz.—

“1741.—A male child, about two months old, with white dimity sleeves, lined with white, and tied with red ribbon.”

“A female child, aged about six weeks, with a blue figured ribbon, and purple and white printed linen sleeves, turned up with red and white.”

“A male child, about a fortnight old, very neatly dressed; a fine holland cap, with a cambric border, white corded dimity sleeves, the shirt ruffled with cambric.”

“A male child, a week old; a holland cap, with a plain border, edged biggin and forehead-cloth, diaper bib, striped and flowered dimity mantle, and another holland one; India dimity sleeves, turned up with stitched holland, damask waistcoat, holland ruffled shirt.”

As to the matter of naming such a large number of infants, Knight explains –

“It has been the practice of the Governors, from the earliest period of the Hospital to the present time, to name the children at their own will and pleasure, whether their parents should have been known or not.

At the baptism of the children first taken into the Hospital, which was on the 29th March, 1741, it is recorded, that “there was at the ceremony a fine appearance of persons of quality and distinction: his Grace the Duke of Bedford, our President, their Graces the Duke and Duchess of Richmond, the Countess of Pembroke, and several others, honouring the children with their names, and being their sponsors.

“Thus the register of this period presents the courtly names of Abercorn, Bedford, Bentinck, Montague, Marlborough, Newcastle, Norfolk, Pomfret, Pembroke, Richmond, Vernon, etc.. etc., as well as those of numerous other living individuals, great and small, who at that time took an interest in the establishment. When these names were exhausted, the authorities stole those of eminent deceased personages, their first attack being upon the church. Hence we have a Wickliffe, Huss, Ridley, Latimer, Laud, Sancroft, Tillotson, Tennison, Sherlock, etc., etc. Then come the mighty dead of the poetical race, viz.—Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakspeare, John Milton, etc. Of the philosophers, Francis Bacon stands pre-eminently conspicuous. As they proceeded, the Governors were more warlike in their notions, and brought from their graves Philip Sidney, Francis Drake, Oliver Cromwell, John Hampden, Admiral Benbow, and Cloudesley Shovel. A more peaceful list followed this, viz.—Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony Vandyke, Michael Angelo, and Godfrey Kneller; William Hogarth, and Jane, his wife, of course not being forgotten. Another class of names was borrowed from popular novels of the day, which accounts for Charles Allworthy, Tom Jones, Sophia Western, and Clarissa Harlowe. The gentle Isaac Walton stands alone.

“So long as the admission of children was confined within reasonable bounds, it was an easy matter to find names for them; but during the ” parliamentary era” of the Hospital, when its gates were thrown open to all comers, and each day brought its regiment of infantry to the establishment, the Governors were sometimes in difficulties; and when this was the case, they took a zoological view of the subject, and named them after the creeping things and beasts of the earth, or created a nomenclature from various handicrafts or trades. In 1801, the hero of the Nile and some of his friends honoured the establishment with a visit, and stood sponsors to several of the children. The names given on this occasion were Baltic Nelson, William and Emma Hamilton, Hyde Parker, etc.

“Up to a very late period the Governors were sometimes in the habit of naming the children after themselves or their friends; but it was found to be an inconvenient and objectionable course, inasmuch as when they grew to man and womanhood, they were apt to lay claim to some affinity of blood with their nomenclators. The present practice therefore is, for the Treasurer to prepare a list of ordinary names, by which the children are baptized.

|

| © Coram Family in the care of the Foundling Museum |

“The children are all disposed of by apprenticeship: the girls at the age of fifteen to domestic service, for a term of five years, and the boys at the age of fourteen as mechanics, &c. for a term of seven years. The trades to which the latter have been apprenticed during the last seven years are as follows, viz.:— tailors, sixteen; boot and shoe makers, sixteen; fishermen, seven; cabinet makers, four; linen drapers, three; confectioners, two; bakers, two; gold beaters, two; hair dressers, three; hair manufacturers, two; silver smith, one; opticians, two; tin plate worker and ironmonger, ‘one; general provision dealer, one; weaver, one; law writers, two; watch maker, one; pawnbrokers, three; soda water manufacturer, one; cooper, one; dyer, one; paper hanger, one; furnishing undertaker, one; brass, copper, and iron wire drawer, one; silk hat manufacturer, one; domestic service, four; in all eighty apprentices. A very satisfactory report was recently made of their conduct and destination, four only excepted. These have left their masters, owing to disagreements; but are believed to be leading reputable lives.

|

| Girls exercising at the London Foundling Hospital © Coram Family in the care of the Foundling Museum |

With respect to the girls, it appeared by a recent investigation, that of all those apprenticed during the last five years, there was only one whose conduct had been faulty, and she was redeeming her character by subsequent good behaviou

r.

r.

|

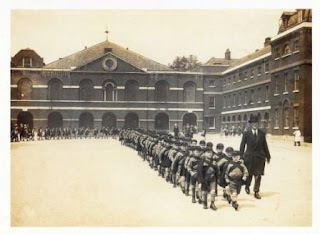

| Boys marching out of the London Foundling Hospital for the last time, 1926 © Coram in the care of the Foundling Museum |

Whilst running a charity of such a size was not without its problems, some might say horrors, over the centuries, thousands of children’s lives were saved: some 27,000 children, before the 1952 Children Act changed the way charities operated. The Foundling Hospital finally closed its doors in 1954 and became the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, which continues to benefit the children of London to this day.