|

| Henry Purcell |

|

| Sledmere House – Yorkshire |

|

| Tatton Park – Cheshire |

|

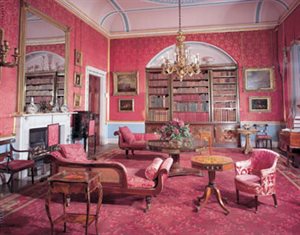

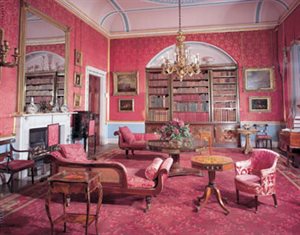

| Music room at Tatton Park |

|

||

| Dove sei by G.F. Handel (from the Samuel Arnold collection at Tatton Park) |

|

| Henry Purcell |

|

| Sledmere House – Yorkshire |

|

| Tatton Park – Cheshire |

|

| Music room at Tatton Park |

|

||

| Dove sei by G.F. Handel (from the Samuel Arnold collection at Tatton Park) |

Victoria and I are thrilled to announce that our dear friend Louisa Cornell has joined the Number One London editorial team. We couldn’t be happier! Many of you will already know Louisa who, in addition to her editorial work and her own writing projects, is also President Elect of the Beau Monde Chapter of Romance Writer’s of America.

Louisa has been a friend of this blog since it’s beginnings six years ago and has been a friend to Victoria and myself for a considerably longer period of time (decades!).

| Louisa, on the left, with Victoria at one of the many writing conferences they’ve attended through the years. |

As a champion of romantic fiction and all things British, Louisa will be bringing her unique talents and her passion for researching the history of Great Britain to Number One London soon and you can look forward to reading her enlightening posts, reviews of fiction and non-fiction books and to many surprises yet to be announced.

And a note from Louisa –

I cannot begin to tell you what a thrill and honor it is to join the Number One London team! I think I’ve spent so much time loitering about here the last six years, Victoria and Kristine have decided to put me to work. And I could not be happier! This blog has been and continues to be a delightful respite from the everyday world, a lovely neverending vicarious vacation to the UK, and a source of entertainment and enlightenment for all who love 18th and 19th century England and the romances set in those eras. I look forward to contributing in my own small way to the myriad charms enjoyed by the most discerning, supportive, and loyal denizens on the web – Our Visitors!

Thank you so very much, Kristine and Victoria!

And thank you to Number One London’s Fabulous Followers!

And while we’re at it, Victoria, Kristine and Louisa would like to thank all of our guest bloggers who have contributed to the blog in the past. Our most prolific (and much loved) pal, author Jo Manning has been providing guest posts to Number One London since the beginning, with many of her posts featuring 18th and 19th century artists and their sitters. Look for more book reviews and posts from Jo coming soon. Over the past year, we’ve welcomed guest posts from the following authors: Abigail Dane, Marilyn Clay, Louise Allen, Diane Gaston (Perkins), Beth Elliot, Cheryl Bolen, Amanda McCabe, Tracy Grant, Kerryn Reid and Michelle Styles. If you’ve uncovered an historic tidbit you’d like to post about, or a favourite his

toric person, place or thing, please do get in touch. We’d love to add you to our roster of guest bloggers.

|

| Boston House, Brentford |

Our series on the lives of King William IV and Queen Adelaide continues with excerpts from a book entitled, Letters the Late Miss Clitherow of Boston House, Middlesex, With A Brief Account of Boston House and the Clitherow Family, edited by Rev. G. Cecil White. As the Reverend himself states in his preface: “The following pages are mainly compiled from certain letters by Miss Mary Clitherow, which have come into the editor’s possession. They afford glimpses of the Court at that time, with reference not so much to public functions as to their Majesties’ more private relations with persons honoured with their friendship.”

Our next glimpse of their Majesties is not from, but at Boston House. This unsought honour was rather deprecated, though thoroughly appreciated by their hosts, who, in spite of their intimacy with the King and Queen, never made any pretension to be more than simple gentlefolk. Colonel Clitherow was the first commoner whom William IV so honoured, probably the only one, and instances of other monarchs doing the like must be few and far between. In this case, doubtless, both their Majesties regarded it as an act of simple friendship, and not in any way as one of condescension.

'BOSTON HOUSE, 'July 10, 1834.

'On June 28, 1834, their Majesties honoured old Boston House with their company to dinner. They came by Gunnersby and through our farm at our suggestion; it is so much more gentlemanly an approach than through Old Brentford.

'The people were collected in numbers and Dr. Morris's school, and they gave them a good cheer. We then let the boys through the garden into the orchard by the flower-garden, where my brother had given leave for the neighbours to be, and it seemed as if two hundred were collected.

'We had our haymakers the opposite side of the garden, and kept the people, hay-carts, etc., for effect, and it was cheerful and pretty. The weather was perfect, and the old place never looked better.

'They arrived at seven, and we sat down to dinner at half-past. During that half hour the Queen walked about the garden, even down to the bottom of the wood. The haymakers cheered her, and had a pail of beer, and when she came round to the house, instead of turning in she most good-humouredly walked on to the flower-garden, and stood five minutes chatting to the party, which gave the natives time to get her dress by heart. It was very simple--all white, little bonnet and feathers.

'The King had a slight touch of hay asthma, the Princess Augusta a slight cold, and therefore they declined going out, which separated the party, and was a great disappointment to the people. We had police about to keep order, the bells rang merrily, and all went well. We received them in our new-furnished library.

'When dinner was announced the King took Jane, my brother the Queen, and they sat on opposite sides, the Duchess of Northumberland[*] the other side of the King, Lord Prudhoe[**] the other side of the Queen, General Clitherow and General Sir Edward Kerrison top and bottom, and the rest as they chose--Princess Augusta, Lord and Lady Howe, Lady Brownlow,[***] Lady Clinton,[****] Lady Isabella Wemyss, Colonel Wemyss, Miss Clitherow, Miss Wynyard, Mrs. Bullock, and Mr. Holmes. That makes nineteen. The Duke of Cumberland[*****] was to have been the twentieth, but Mr. Holmes brought a very polite apology just as we were going in to dinner. The House of Lords detained him.

Princess Augusta Sophia, sister of King William IV

'As to the dinner, it was so perfect that it was impossible to know a single thing on the table, and that, you know, must be termed a proper dinner for such a party. My brother gave a carte blanche to Sir Edward Kerrison's Englishman cook, and, to give him his due, he gave us as elegant a dinner as ever I saw. Our waiting was particularly well done--so quiet, no in and out of the room. Everything was brought to the door, and there were sideboards all round the room, with everything laid out to prevent clatter of knives, forks, and plates. Etiquette allows the lady's own footman in livery, and we had ten out of livery, the King and Queen's pages, seven gentlemen borrowed of our friends, and our own butler. They all continued waiting till the ladies left the room.

'We were well lit, wax on the table and lamps on the sideboards, and many a face I saw taking a peep in at the windows. The room was cool, for the Queen asked to have the top sashes down.

'The King was not in his usual spirits. He said had it been the day before he must have sent his excuses. The Queen was all animation, and the rest of the party most chatty and agreeable. The King bowed to the Queen when the ladies were to move.

'Our evening was short, as they went at half-past ten. The Princess played on the piano, and my brother and Mrs. Bullock sang one of Ariole's duets at the Queen's request. When they went the sweep was full of people to see them go, and their Majesties were cheered out of the grounds.

|

| King William IV |

'We had with us our little nephew Salkeld,[*] whom my brother puts to Dr. Morris's school. H

e came in to dessert, a day the child can never forget. The King asked him many questions, which he answered distinctly, with a profound bow, and then backed away. He looked so pretty, for the awe of Royalty brought all the colour to his cheeks. I felt rather proud of him, he did it so gracefully. The Queen told him she hoped he would make as good a man as his excellent uncle. After dinner the Princess Augusta called him to her in the drawing-room, saying, "I like that little fellow's countenance; he is quite a Clitherow." She talked to him of cricket, football, and hockey, telling him when she was a little girl she played at all these games with her brother, and played cricket particularly well.

'That we are proud of this day we cordially own, for my brother is the first commoner their Majesties have so honoured; but we feel we ought not to have done it. When Jane, with her honesty, told the Queen we were not in a situation to receive such an honour, her answer was: "Mrs. Clitherow, you are making me speeches. If it is wrong I take the blame, but I was determined to dine once again at Boston House with you.'

'The absurd conjecture of people at the expence of the day to my brother induces me to tell you what it actually was, as we should be ashamed at the sum guessed at. I have made the closest calculation I possibly can, which includes fees to borrowed servants, ringers, police, carriage of things from and to London, and I have got to L44. Never was less wine drank at a dinner, and that I cannot estimate, but L6, I think, must cover that. We had two men cooks, for he brought his friend, and we got all they asked for. Really, I think we were let off very well at L50.

[*] Wife of Hugh, third Duke, and daughter of the first Earl Powis. She was governess to H.R.H. the Princess Victoria, our late gracious Queen.

[**] Algernon Percy, second surviving son of the second Duke of Northumberland, F.R.S., and Captain R.N.; born 1792. Created Baron Prudhoe 1816. On the death of his brother he succeeded to the dukedom, which, on his death in 1865, passed to his cousin, the second Earl of Beverley.

[***] Emma Sophia, daughter of the second Earl of Mount Edgecumbe; born 1791, married, 1828, the first Earl Brownlow. She was Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Adelaide.

[****] Widow of the seventeenth Baron Clinton, Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Adelaide. In 1835 she married Sir Horace Beauchamp Seymour, K.C.H.

[*****] He became King of Hanover on the death of William IV.[*] He became a hero in the Indian Mutiny, losing his life in volunteering to blow up the Cashmere Gate at Delhi in 1857.

|

| Queen Adelaide |

AFTER a short illness, William IV. died at Windsor Castle on June 20, 1837. On July 17 Miss Clitherow wrote as follows:

'Thank you very much for writing to me. I always enjoy your letters, and delight to hear from you. I feel I did not deserve it, so much time has elapsed since I wrote to you. But I dislike writing when the spirits are below par, and how could they be otherwise with the afflicting event which has befallen the country? Great were our apprehensions for the dear Queen when she was so ill and could attend none of the State entertainments, but the King's death never entered our ideas. On June 3 my brother went by command to Windsor. He sat with

the King while he ate his early dinner. He was cheerful and chatty, and had only sent for him for the pleasure of seeing and conversing freely with him, which he did for above an hour, and the last thing his Majesty said was, "Thank you for coming; it always does me good to see you, and very soon you and Mrs. Clitherow must come to Windsor for a few days and your sister.' How little he thought his days were numbered, and that he should never see him more! He then appeared so little ill my brother returned home quite in spirits, and on the

twentieth he was dead--only seventeen days.

'Since the Queen Dowager got to Bushey Lady Gore has written to us. The description of her resigned pious mind is beautiful, and Lady Gore[*] assures us she really hopes her health has not materially suffered from all she has gone through, particularly the last sad ceremony.

'My brother was deputed to present the address of condolence from the magistrates to the Dowager Queen. He dreaded it, but he wrote to Lord Howe to know how and when, and was answered--Queen Adelaide receives no addresses; but those she received on the throne from the City, etc., those she must receive. We are delighted at this, as it was too much to impose upon her. Addresses are pouring in from all quarters, and Lord Howe is to receive them.'

[*] Wife of General Hon. Sir Charles Gore, G.C.B., K.H., third son of the second Earl of Arran, a Waterloo officer.As Queen Adelaide received no visitors, except such as she could not refuse, in her widowhood, the King's death closed her intimate intercourse with the Clitherows. It seems, however, just to the memory of both the King and Queen to insert the following testimony to her tender affection for her husband, and her delicacy of feeling respecting his previous relations with Mrs. Jordan.

|

| Dorothea Jordan by Hopper |

BOSTON HOUSE, September 23, 1837. 'I dare say you look to me for some true account of our dear Queen Adelaide. We have not seen her, but have been much gratified by her recollection of us. She sent a most kind message by Mr. Wood, with the little book he wrote at her command of William IV.'s last days--a copy to my brother and one to me. 'Very lately we began to doubt whether we ought not to go to Bushey as we used to visit her Majesty at Windsor, and Mrs. Clitherow wrote to consult Lady Denbigh. She acted most kindly to us, for she waited an opportunity of showing the note to the Queen. Her Majesty's answer was, it would be a 'real comfort to her to see Mrs. Clitherow, but it would open the door to so many; she could not without giving great offence. Lady Denbigh added Her Majesty had received no one yet, except those whom she was obliged to admit. 'Mrs. Clitherow dined in company with Miss Hudson, one of the Dowager's Maids of Honour, whom we know very well. She gave a delightful account of the dear Queen, her mind so peaceful, always occupied, much interested with her sister and her children, constantly doing charitable acts, and for ever talking of the King, and hoping she had thoroughly done her duty. Miss Hudson was in waiting for five weeks, and the first three she was very uneasy about Her Majesty's health, and thought her sadly altered; but the last two her cough had almost entirely ceased, and she had slept remarkably well. 'You have no doubt seen the book I allude to, for 'tis now to be had for sixpence. Could anything be so extraordinary as the conduct of the Bishop of Worcester? Her Majesty sent him a copy, and he sent it to the editor of a newspaper. When the Queen read it in a public paper she was very indignant, and the gentleman who was told by her to discover who "the high dignitary in the Church" was, told us Carr, Bishop of Worcester. The man who has been quite the Court Bishop should have known better. 'One act of the Queen Dowager I must tell you: the Queen (Victoria) sent a message by Colonel Wood and Sir Henry Wheatley requesting she would take anything she chose from the Castle; she selected two--a favourite cup of the King's, in which she had given him everything during his last illness, and the picture from his own room of all his family. It was a singular picture, all the Fitz-Clarences grouped, and in the room Mrs. Jordan hanging a picture on the wall, the King's bust on a pedestal, and all strikingly like. I think it shows a delicacy of feeling to her King which was beautiful. It was a picture better out of sight for his memory. Now, this you may believe, for Colonel Wood told us. He transacted the business, and Queen Adelaide has the picture. 'Believe me, 'Yours very truly, Mary Clitherow.' Neither Queen Adelaide nor the three friends long survived the kindly monarch they loved so well. Colonel Clitherow died in 1841; his sister, who became totally blind, early in 1847; and his true and honest wife, the last of the Boston House trio, died in March of the same year.

|

| Windsor Castle |

Our series on the lives of King William IV and Queen Adelaide continues with excerpts from a book entitled, Letters the Late Miss Clitherow of Boston House, Middlesex, With A Brief Account of Boston House and the Clitherow Family, edited by Rev. G. Cecil White. As the Reverend himself states in his preface: “The following pages are mainly compiled from certain letters by Miss Mary Clitherow, which have come into the editor’s possession. They afford glimpses of the Court at that time, with reference not so much to public functions as to their Majesties’ more private relations with persons honoured with their friendship.”

Within a week or two after their last royal summons, Colonel and Mrs. Clitherow again

visited Windsor by the Royal commands, and Miss Clitherow, in her minute chronicle, shows that, while they cherished no pride of pomp or station, they fully appreciated the honour of the King's friendship:

BOSTON HOUSE, May 13, 1832.

'. . . . . . I will tell you of our Courtly doings, and how thankful we are that we just take the cream, free and independent, without rank or place--no troubles, turmoils, or jealousies. We receive the most flattering notice--and it can be from no other motive than liking us--a rare

occurrence at Court, and of which we have a right to be proud.

'Lately a command came to my brother and Mrs. Clitherow to come to Windsor Castle on the Monday and stay till the Wednesday. There were no other visitors. Nobody breakfasts with the Queen or takes luncheon unless sent for. You have your breakfast in your own sitting-room, or at the general breakfast, as you prefer. We always take the latter, but

this visit Jane was with her at every meal, the King the only gentleman admitted at breakfast, and only his sons, or very few, at luncheon. Each evening the Queen called Jane to her sofa and work-table, where, also, no one approaches but by her invitation, and on the Tuesday morning the King took my brother all round the Castle with Wyattville, giving orders and directions. I fear greatly the improving mania is coming upon His Majesty, which, in these times, will be very unfortunate.

'The Queen took my brother and Jane a long drive in her barouche. . . . . . After the drive she took them into her room, and clasped a bracelet round Jane's arm, begging her to wear it for her sake, and, as the stone was an amethyst, the A would remind her of Adelaide, and then she kissed her cheek. To my brother she presented a silver medallion of the King, telling him her name was on the back, and he must keep it for her sake. She always has something obliging and kind to say. She sent a ticket for her box at Drury Lane. It was "Admit Colonel and Mrs. Clitherow." Jane asked her if that meant two places. "No, no; the whole box, to be sure. It holds eight. But, when I name one of you, I cannot help naming both."

|

| Sir Jeffry Wyatville |

'King William IV. forgot little me when he sent his commands. On their going in he said: "Where is Miss Clitherow? I hope illness has not prevented her.' On an explanation, "Then next Monday meet us at dinner at Bushey, and bring your sister with you.' And we did meet them. The King came over with Wyattville to inspect Hampton Court Palace. The Queen followed, to dine with him at their dear Bushey. They returned to Windsor at ten, the Princess Augusta to town. Only Lady Falkland and Miss Wilson attended the Queen. The company were the inmates of Hampton Court, where we have never visited, and therefore to me the dinner was dull.'

'. . . . . .The Thursday after we went to see Lady Falkland, who is on a visit to papa King. We found her, her widowed sister Lady Augusta Kennedy, and Miss Wilson very comfortably at work. They were the two Fitz-Clarences; we saw a good deal of them when they lived at Bushey.

|

| King William IV |

'A page soon came to conduct my brother to the King, another to desire we would take luncheon in the Queen's room. On entering the King called Jane by him, the Queen me; she rose up and shook hands with both. My brother went down to the general luncheon. Nothing could be more good-humoured and pleasant than they were. The King was cheerful but

silent; 'twas the day after Lord Grey's resignation. The Queen certainly in particular good spirits; the King's firmness respecting the making no peers had delighted her. They went to his apartments, and we to Lady Falkland's, and were preparing to depart, when a message

came. The Queen had not taken leave of us, and hoped we were in no hurry, but would stay and Walk with her. Of course we did. The party consisted of the Queen, Miss Eden (Maid of Honour), Miss Wilson, Lord Howe, Mr. Ashley, Mr. Hudson, Sir Andrew Barnard, and our three selves. She took us through the slopes to her Adelaide Cottage and her flower-garden to see Prince George of Cambridge at gymnastics, with half a dozen young nobility from Eton, who came once a week to play with him. We were walking nearly two hours. The Queen is very animated, and Mr. Ashley and Mr. Hudson full of fun and tricks, and amused us all much. In short, I ha

ve but one fear when with her--forgetting in Whose presence I am; her manner is so very kind, but there is dignity with it that keeps us in order.'

|

| The Fishing Temple, Virginia Water |

'WINDSOR CASTLE, 'September 3, 1832.

'Here I am writing with Royal pens, ink, and paper, which last I dislike of all things, it being glazed. . . . The visitors here besides ourselves are the Duke and Duchess of

Gloucester[*]--she is too unwell to appear--Prince George of Cambridge; the Duke of Dorset; Mademoiselle d'Este; Sir Henry and Lady Wheatley, with two daughters; Lady Isabella Wemyss (Lady of the Bed-chamber), a most pleasing, lovely woman, sister to Lord Errol; Miss Johnson (Maid of Honour); Miss Wilson (Bed-chamber-woman); Mademoiselle Marienne, Lord and Lady Falkland, Sir Herbert and Lady Taylor, Sir Andrew Barnard, Sir Frederick Watson, Colonel Bowater, Mr. Hudson, Mr. Shifner, and Mr. Wood.[**] Princess Augusta and Lady Mary Taylour came every day from Frogmore, which, with the household medical man, Mr. Davis, makes a party of thirty, reckoned here a small party.

'The dinners are always princely, gold plate, quantities of wax-lights, and servants innumerable, yet very agreeable and with less of form than you could suppose possible.

'Yesterday threatened much rain, but after luncheon it cleared, and we started, four carriages, four in each and a number on horseback, and went to the Fishing Temple by the Virginia Water to see a model of a vessel to be moved by clockwork. After seeing it exhibited we all took boat, and in parties rowed about that beautiful lake. We had the

six-oared boat and various little boats. Prince George and Mr. Hudson rowed Her Majesty about, and the whole had so much ease and good-humour it was very delightful.

'Our evenings are always the same, the band playing most beautifully, work-tables and cards for those who chuse.

'The first evening the Queen called us both to her table; the second she sat with the Duchess of Gloucester till her bedtime, so that we had not much of her company. She is always about some elegant work, which she does remarkably well, and has a great deal of cheerful conversation.

'This is our third day, and we leave on Monday. Our invitations say when we are to come and when to go, which is very agreeable. We have our time to ourselves in our own sitting-room from breakfast till luncheon at two.

'So I have scribbled to you, though no post goes till to-morrow. A trio of kind regards.

'Yours truly, 'M. CLITHEROW.'

[*] H.R.H. was the King's cousin, and the Duchess was the King's fourth

sister, Princess Mary.

[**] Many of these are obviously members of the household rather than

visitors.

The following letter offers a splendid description of the festivities at Windsor for the Queen's birthday and was written from Rise Park, the seat of their cousin, Mr. Bethell,

M.P., on October 1, 1833:

'. . . . . . .Now, from the Fens I will take you to the Forest. The cottage where George IV. lived so much has been pulled down, except a banquetting room, the conservatory, and a few small rooms for the gardener. Here the preparations were made for a morning fete on the Queen's birthday [August 13], and, as a surprise to her, the magnificent Burmese tents,

which she had never seen, were put up. I never saw anything prettier than the whole scene, and the day was lovely. The tents the most brilliant scarlet, ornamented with gold and silver, silver poles, and a silvered velvet carpet, embroidered with gold and silver. The hangings,

sofas, and seats were all of Eastern splendour, and at the end was a large glass. The company was very select, and the morning dresses becoming and elegant. Two bands of music (Guards) played alternately. A guard of honour and numbers of officers were present. Everybody seemed gay and in their best fashion. The King and Queen, with about forty

guests, dined in the room, about as many more in a long, canvas room. The tables had fruit, flowers, ornaments, confectionery, a few pyramids of cold tongue, ham, chicken, and raised pies. Then you had handed to you soups, fish, turtle, venison, and every sort of meat. Toasts were given, cannon fired, and both bands united in the appropriate national airs. Altogether it was a sort of enchantment. At seven fifteen of the King's carriages and many private carriages took the party to the Castle to dress for an evening assembly, where about two hundred were asked. We were the envy of many in being allowed to go home, having had the cream of the day. Nothing could be a greater compliment than our being asked in the morning. We were the only untitled people. The King had filled the Castle, Round Tower, and Cumberland Lodge, and had not a bed to offer. So he invited us, saying: "Come at three. We dine at four. And then go away at seven, and be home by daylight, for we cannot

give you beds."

|

| Windsor Castle |

'To his own birthday [August 21] we had the general invitation for the evening, and the old trio went from Boston House at seven, and got back by two. The noble Castle, so lit up, was a magnificent sight. The Queen was quite the Queen, for it was very mixed society--too much so for Royal presence. The good-humoured King asks everybody, and it was a

crowd! But she sat with the Royal Duchesses only, attended by her ladies, and she was dressed much finer than her usual style. She twice conversed with us, and when she left the room came up to us, shook each by the hand, and

was so sorry we had to go home so far.

'My brother and Mrs. Clitherow called at Windsor to take leave before we left home for so many weeks, and after luncheon with her and the King, she took them into her own room to see a bust of the little niece that she nursed with such motherly affection, Princess Louise, and then gave them two prints of herself and two of Prince George of Cambridge, the best likeness I have seen of her. She said, "One for Miss Clitherow, the other for you two, because you are as one." All she does in such a gracious, pretty manner.'

PART THREE COMING SOON!