Lead in with ruined country house photos – then Photo round up of homes we’ll be visiting on Country House Tour

A GEORGIAN TOUR POST HERE

TEA & VALENTINES by Guest Blogger Marilyn Clay

A ROOM BY ANY OTHER NAME – Those Regency Ladies Are At It Again!

Perhaps one of the first set of house plans which recorded a specific room dedicated to music was drawn by no less a designer than Robert Adam himself. In 1760, as lead architect for the creation of Sir Nathaniel Curzon’s showplace – Kedleston Hall – Adam drew plans for a neoclassical Temple of Art which encompassed an enfilade on one entire side of the entrance hall. It consisted of a music room, a drawing room, and a library. These rooms were so labelled in a catalogue printed in 1769, which was used to guide tourists around the house. This catalogue was reprinted at least four times by 1800 and would have been well-known to any wealthy landowner and / or peer looking to build or renovate a home.

|

||||

| The Music Room at Kedleston Hall |

|

||||

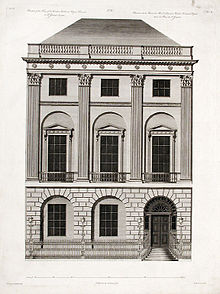

| Robert Adam’s design for the front facade of No. 20 St. James Square. |

|

||

| Robert Adam’s design for the Music Room ceiling at No.20 St. James Square |

|

||

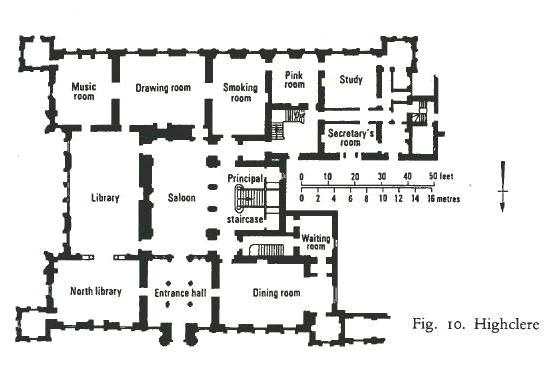

| Music Room Highclere Castle. Notice the double doors to the left. |

|

|||||

| Floor plan of Highclere Castle. Notice the position of the music room as anchor to the drawing room and library. |

WATERLOO'S AFTERMATH, PART TWO

After the Battle on the 18th of June, Napoleon tried unsuccessfully to re-group. Unable to sort out the demoralized and scattered sildiers, he turned over command of his armies to General Soult and fled to Paris. The armies had about 150,000 troops stationed around France, including General Grouchy’s 60,000, who returned to Laon by June 26. Another 175,000 (?) conscripts were in training. There were also General Rapp’s Armee of the Rhine and General Lamarque’s Armee of La Vendee, still in place waiting for the Austrians and Russians. Napoleon wanted to continue the war, but he needed political and financial support.

Napoleon was unsuccessful in getting the Chamber of Deputies — or anybody else except his closest confidantes — to agree to renew the war.

The hero of the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) spoke against Napoleon in the Chamber, in answer to pleas of the disgraced emperor by his brother Lucien Bonaparte. Lafayette said:

Lafayette’s views prevailed and Napoleon was rejected. His attempted abdication in favor of his four-year-old son on June 22 (and by some reports, a failed suicide) was ignored by the Allies.

Fouché, president of the new provisional government, sent word Napoleon should leave Paris. Napoleon stayed for a few days at his late first wife’s chateau, Malmaison, just west of Paris. Here he and Josephine(who died in 1814) had enjoyed happiness and success. How he must have yearned for those days to return.

The Prussians were approaching by June 29, and he did not want to be captured. When he got word from the provisional government that he was not be issued any safe conduct by Blücher or Wellington, Napoleon decided to travel to the Atlantic coast and find a ship to take him to the United States, where he hoped to find refuge; he arrived in Rochefort on July 3. However, the British blockade, in effect again since his escape from Elba, made that impossible. Instead, he negotiated his surrender to Captain Frederick Maitland aboard the HMS Bellerophon on July 15.

An amusing aside: Upon boarding the HMS Bellerophon, Napoleon took over the cabin of the Captain and invited him and others to breakfast with him. Captain Humphrey Senhouse, captain of another ship in the fleet, later wrote to his wife: “I have just returned from dining with Napoleon Bonaparte. Can it be possible?”

In the meantime, the Allies had entered Paris on July 7, 1815, and successfully arranged for Louis XVIII to take the throne, which he did on July 8.

The Bellerophon sailed to Torbay arriving July 24 and on to Plymouth where Napoleon became a sort of tourist attraction as people hired boats to go out and see him aboard the Bellerophon where he was kept.

On August 7, he was transferred to the HMS Northumberland for the voyage to his imprisonment on the Island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, arriving August 17.

St. Helena is more than 1,200 miles from the nearest landmass. He lived there, until his death on May 5, 1821.