“Brussels, 2d July, 1815.

“This country, the finest in the world, has been of late quite out of our minds. I did not, in any degree, anticipate the pleasure I should enjoy, the admiration forced from me, on coming into one of these antique towns, or in journeying through this rich garden. Can you recollect the time when there were gentlemen meeting at the Cross of Edinburgh, or those whom we thought such? They are all collected here. You see the very men, with their scraggy necks sticking out of the collars of their old-fashioned square-skirted coats— their canes—their cocked-hats; and, when they meet, the formal bow, the hat off to the ground, and the powder flying in the wind. I could divert you with the odd resemblances of the Scottish faces among the peasants, too—but I noted them at the time- with my pencil, and I write to you only of things that you won’t find in my pocket-book.

“I have just returned from seeing the French wounded received in their hospital; and could you see them laid out naked, or almost so—100 in a row of low beds on the ground—though wounded, exhausted, beaten, you would still conclude with me that these were men capable of marching unopposed from the west of Europe to the east of Asia. Strong, thickset, hardy veterans, brave spirits and unsubdued, as they cast their wild glance upon you,—their black eyes and brown cheeks finely contrasted with the fresh sheets,—you would much admire their capacity of adaptation. These fellows are brought from the field after lying many days on the ground; many dying— many in agony—many miserably racked with pain and spasms; and the next mimicks his fellow, and gives it a tune,—Aha, vous chantez bien! How they are wounded you will see in my notes. But I must not have you to lose the present impression on me of the formidable nature of these fellows as exemplars of the breed in France. It is a forced praise; for from all I have seen, and all I have heard of their fierceness, cruelty, and bloodthirstiness, I cannot convey to you my detestation of this race of trained banditti. By what means they are to be kept in subjection until other habits come upon them, I know not; but I am convinced that these men cannot be left to the bent of their propensities.

“This superb city is now ornamented with the finest groups of armed men that the most romantic fancy could dream of. I was struck with the words of a friend —E.: ‘I saw,’ said he, ‘that man returning from the field on the 16th.’—(This was a Brunswicker of the Black or Death Hussars.)—’ He was wounded, and had had his arm amputated on the field. He was among the first that came in. He rode straight and stark upon his horse—the bloody clouts about his stump—pale as death, but upright, with a stern, fixed expression of feature, as if lothe to lose his revenge.’ These troops are very remarkable in their fine military appearance; their dark and ominous dress sets off to advantage their strong, manly, northern features and white mustachios; and there is something more than commonly impressive about the whole effect.

“This is the second Sunday after the battle, and many are not yet dressed. There are 20,000 wounded in this town, besides those in the hospitals, and the many in the other towns;—only 3000 prisoners; 80,000, they say, killed and wounded on both sides.”

I think it not wonderful that this extract should have set Scott’s imagination effectually on fire; that he should have grasped at the idea of seeing probably the last shadows of real warfare that his own age would afford; or that some parts of the great surgeon’s simple phraseology are reproduced, almost verbatim, in the first of “

Paul’s Letters to his Kinsfolk.”At Brussels, Scott found the small English garrison left there in command of Major-General Sir Frederick Adam, the son of his highly valued friend, the present Lord Chief Commissioner of the Jury Court in Scotland. Sir Frederick had been wounded at Waterloo, and could not as yet mount on horseback; but one of his aides-de-camp, Captain Campbell, escorted Scott and his party to the field of battle, on which occasion they were also accompanied by another old acquaintance of his, Major Pryse Gordon, who being then on halfpay, happened to be domesticated with his family at Brussels. Major Gordon has since published two lively volumes of ” Personal Memoirs;” and bears witness to the fidelity of certain reminiscences of Scott at Brussels and Waterloo, which occupy one of the chapters of this work. I shall, therefore, extract the passage.

|

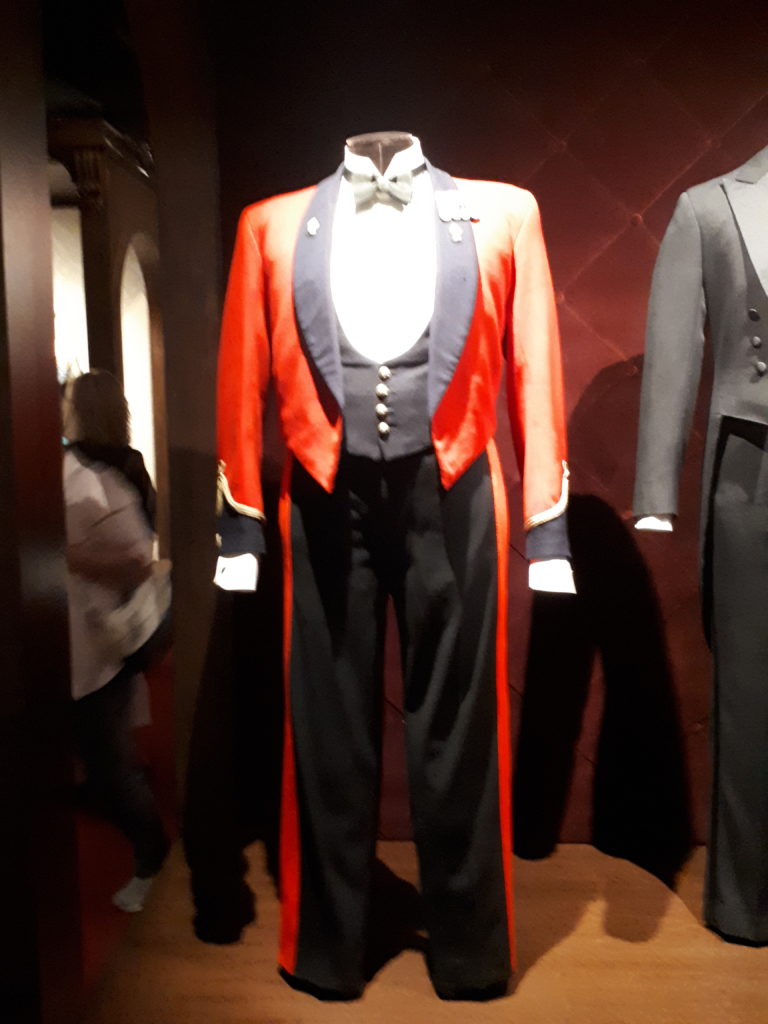

| Louis-Victor Baillot, last French veteran of Waterloo |

“Sir Walter Scott accepted my services to conduct him to Waterloo: the General’s aide-de-camp was also of the party. He made no secret of his having undertaken to write something on the battle; and perhaps he took the greater interest on this account in every thing that he saw. Besides, he had never seen the field of such a conflict; and never having been before on the Continent, it was all new to his comprehensive mind. The day was beautiful; and I had the precaution to send out a couple of saddle-horses, that he might not be fatigued in walking over the fields, which had been recently ploughed up. In our rounds we fell in with Monsieur de Costar, with whom he got into conversation. This man had attracted so much notice by his pretended story of being about the person of Napoleon, that he was of too much importance to be passed by: I did not, indeed, know as much of this fellow’s charlatanism at that time as afterwards, when I saw him confronted with a blacksmith of La Belle Alliance, who had been his companion in a hiding-place ten miles from the field during the whole day; a fact which he could not deny. But he had got up a tale so plausible and so profitable, that he could afford to bestow hush-money on the companion of his flight, so that the imposition was but little known; and strangers continued to be gulled. He had picked up a good deal of information about the positions and details of the battle; and being naturally a sagacious Wallon, and speaking French pretty fluently, he became the favourite cicerone, and every lie he told was taken for gospel. Year after year, until his death in 1824, he continued his popularity, and raised the price of his rounds from a couple of francs to five; besides as much for the hire of a horse, his own property; for he pretended that the fatigue of walking so many hours was beyond his powers. It has been said that in this way he realized every summer a couple of hundred Napoleons.

“When Sir Walter had examined every point of defence and attack, we adjourned to the ‘Original Duke of Wellington’ at Waterloo, to lunch after the fatigues of the ride. Here he had a crowded levee of peasants, and collected a great many trophies, from cuirasses down to buttons and bullets. He picked up himself many little relics, and was fortunate in purchasing a grand cross of the legion of honour. But the most precious memorial was presented to him by my wife—a French soldier’s book, well stained with blood, and containing some songs popular in the French army, which he found so interesting that he introduced versions of them in his ‘Paul’s Letters;’ of which he did me the honour to send me a copy, with a letter, saying, ‘that he considered my wife’s gift as the most valuable of all his Waterloo relics.'”