by Kristine Hughes Patrone

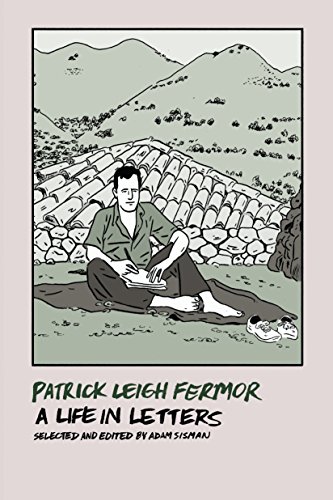

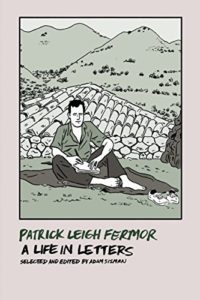

Selected and edited by Adam Sisman, a New York Review Book, 2016 (available through Amazon)

I have so much to thank James Lees Milne for, really. It was through reading his diaries and letters that I have found so many flamboyant, larger-than-life, madcap and interesting people. He introduced me to a circle of his friends and acquaintances and a time period that has become one of my favourite: England between and just after the War(s). One of the people Mr. Lees-Milne introduced me to is Patrick Leigh Fermor, whose author bio on Amazon reads thus:

“In December 1933, at the age of eighteen, Patrick Leigh Fermor (1915-2011) walked across Europe, reaching Constantinople in early 1935. He travelled on into Greece, where in Athens he met Balasha Cantacuzene, with whom he lived – mostly in Rumania – until the outbreak of war. Serving in occupied Crete, he led a successful operation to kidnap a German general, for which he won the DSO and was once described by the BBC as ‘a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene’. After the war he began writing, and travelled extensively round Greece with Joan Eyres Monsell whom he later married. Towards the end of his life he wrote the first two books about his early trans-European odyssey, A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water. He planned a third, unfinished at the time of his death in 2011, which has since been edited by Colin Thubron and Artemis Cooper and published as The Broken Road.”

A potted history, to be sure, and a fuller bio can be found on Wikipedia. A respected British author and travel writer, PLF also felt a pull to Greece, where he travelled extensively and eventually built a house along with his wife, Joan.

But it’s PLF’s circle of friends, also his correspondents, that make this book so interesting. Here again we meet Duff and Diana Cooper, the Devonshires, Andrew and Debo, Evelyn Waugh, Ann Fleming, Cyril Connolly, Lawrence Durrell and a host of others who seemingly all lived out sized lives and who are all people with whom one would have loved to share the odd shaker of martinis. The one slight quibble I had with this book is that it only contains PLF’s letters to people, and none from them, but this can hardly be seen as a flaw when the writing is this good.

While in an army hospital in Surrey recovering from pneumonia in February, 1940, PLF wrote the following to Adrian Pryce-Jones:

“Last night something marvellous happened. I am just being tucked up for the night, when I hear strange foreign noises outside the door, which opens, and in bursts Anne-Marie Callimachi (1) followed by Costa (2). She was dressed in black satin and dripping with mink, with pearls and diamonds crusted at every possible point, topped by the maddest Schiaparelli hat I’ve ever seen. Then Costa, who is very dark, with a huge grin, and quite white hair at the age of thirty. He was dressed in a bright green polo jersey over which he wore a very long black new coat with an immense astrakhan collar: both laden with huge presents. The nurses were struck dumb. Shrill squeals burst from us all, and then we were gabbling the parleyvoo like apes. The nurses fled in disorder. Then, of course, they couldn’t get a taxi as Anne-Marie had left the Rolls Royces etc. in London; but they had their luggage, and stopped the night at the hospital! We all pretended they were married, so the Sister, with girlish squeaks, got their room ready, with screens coyly arranged between the beds. By this time Costa was telephoning to the Ritz to say Her Highness wouldn’t be back that night, his voice echoing down the passages. The sensation in the hospital was absolutely phenomenal. Huge princely coronets on the luggage – such nighties! Slippers! Oh!! The hospital hasn’t recovered yet, and my glamour value among the nurses is at fever pitch. . . . They left this morning, Anne-Marie leaving a munificent cheque for the Hospital Fund, which I tendered with a languid gesture to the head doctor. Their passage will not be forgotten for ages!”

Fourteen years later, in September 1954, such hobnobbing with the cream of society was still in full flow. PLF writing to Ann Fleming from Hydra:

“Diana’s (Lady Cooper) presence proved a magnet for other yachts, first of all Arturo Lopez (3) in a vast sodomitical-looking craft, done up inside like the Brighton Pavilion, a mandarin’s opium den and the alcove of Madame de Pompadour. . . but this is nothing compared to five days ago, when a giant steam yacht (with a aeroplane poised for flight on the stern) belonging to Onassis came throbbing alongside. . . . On board were Lilia Ralli, several blondes, a few of the zombie-men that always surround the immensely rich, Pam Churchill & Winston Jr.”

We can forgive PLF his forays into the world of the rich and famous, not only because they’re so amusing, but as these brief interludes are tempered with quiet, bucolic and often mundane passages. To Jessica Mitford, PLF wrote in 1983, “Went to a marvelous sheep sale yester’een with Debo (her sister, Deborah, nee Mitford, Duchess of Devonshire), it was wonderful, faces like the whole of Gilray and Rowlandson, and an auctioneer haranguing, in what sounded like Finnish but was just rustic north country. This is the sort of whirl I like to live in.”

PLF’s friends were generous as well as amusing, several of them allowing he and Joan to use their homes whenever they chose, as was the case with Gadencourt, a manor house in Normandy owned by Sir Walter and Lady Smart – to Patrick Kinross, February 1952 – “They frightfully kindly let me live here for the whole winter. Why don’t you come and move in on your way home?” He also often stayed at a mansion owned by artist Niko Ghika on Hydra. PLF wrote, “He was seldom there, and, with boundless generosity, he lent it to Joan and me for two years.” Additionally, PLF was a regular house guest of such friends as Lady Diana Cooper, staying at her house in Chantilly and the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, spending many Christmas’s with them at Chatsworth House. In February 1960 PLF wrote to Ann Fleming, “Christmas was glorious and went on for ages, consisting of Andrew, Debo and children, Andrew’s mother, Nancy (Mitford) and Mrs. Hammersley, for whom I developed a reciprocated passion. She strikes a wonderful note of bilious gloom about anything.”

Joan and Patrick would eventually build a house in Greece and spent many of their happiest years there, coming back to England regularly and staying at Joan’s family home in Devon. Occasionally, PLF stayed at the Easton Court Hotel in Devon, especially when he was seeking solitude in which to write. In a letter to Lady Diana Cooper, September 1956 –

” . . . . My muse and I are cloistered here, a gale howls down the chimney, cats and dogs come down on the sodden fields outside in an almost unbroken stream and a wind blows that would unhorn cows. I don’t think you’ve ever been here, but it’s a great retiring place for literary purposes, for E. Waugh, & Patrick Kinross and others – I first came here seven years ago with Patrick . . . and have been back several times in extremis . . . It is owned & run by an odd couple, Mrs. Carolyn Postlethwaite Cobb, an elderly American of very improbable shape, now largely bedridden, and her middle-aged ex-lover Norman Webb, a Devonshire chap she met a number of decades ago running a team of donkeys in Biskra or Fez. . . . ”

I found that PLF and I had a lot in common in the end, very odd considering that I’m neither a man, British nor a lover of all things Greek and that I come from a different generation. In a letter to his publisher, Jock Murray in July of 1953, PLF writes that he’d travelled through Greece, finally arriving in Missolonghi by sea:

“Here the great search for Byron’s shoes began. I hadn’t got Lady Wentworth’s (4) letter with me, containing the address . . . I asked all over the town – mayors, local bigwigs, etc. – for a old man who had a pair of Byron’s shoes. . . I tracked him down in the end, a very decent, wall-eyed old man called Charalambi Baigeorgas or Kotsakaris . . . along with a lot of scimitars, yataghans, pistols, powder horns, etc., he produced a parcel, already addressed, on the strength of my letters last year, to Baroness Wentworth. . . . Since then, though, he seems to have fallen in love with them, and (rather understandably) wants to leave them to his children. . . He undid the parcel, and produced a pair of slippers that looked more Turkish, or Moroccan or Algerian (or Burlington Arcade oriental) than Greek . . . . I enclose a sketch and a description of the colours . . . the age looks just about right. I made a tracing of both of them, also of the parts of the soles where the criss-cross tooling is worn smooth, in case it should corroborate, or conflict with, known facts about Byron’s malformation.”

Do admit, these are the sort of lengths I might conceivably go to if the artifact involved Wellington. There’s no information in the book regarding the outcome or provability of the shoe’s being Lord Byron’s but there is PLF’s description of Lady Wentworth herself, and it’ s a pip –

To Lady Diana Cooper, March 1954: “. . . The house (Crabbet Park, Sussex) is untidy as a barn – trunks trussed, and excitingly labelled `LD BYRON’S papers – LDY BYRON’S papers’ in chalk, pictures stacked, furniture piled, wallpaper, curtains etc. exactly the colour and shape of coloured Phiz or Leech . . . . gilt, faded plum and canary, v. grand and dusty. We had rather a mouldy luncheon, ending up with spotted-dog, in a room as full of papers, pictures, horsey accoutrements and favours as a jackdaw’s nest. Lady Wentworth was wearing, as usual, gym-shoes from playing squash, a Badminton skirt to the ground, a woollen shawl, a gigantic and very dishevelled auburn wig that looked as though made of strands from her stallions’ tails gathered off brambles, and on top of this a mushroom-like, real Sairey-Gamp mob-cap, but made of lace and caught in with a Nile-green satin ribbon. Rather a fine, hawky Byronic face under all this, but scarlet patches on the cheeks as from a child’s paint-box; I think she’s eighty-two or three – and a very thin, aristocratic, bleak voice – `have some more spotted-dog?’ sounding like a knell.”

PLF was a writer with projects constantly on the go, but he was easily distracted by passing fancies, often missing deadlines and being forced to write the dreaded mia culpa letter to editors or friends to which he’d promised pieces. In a letter to Lady Diana Cooper in November of 1975, PLF confesses: “Michael Stewart has sent us the Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names, which I’ve been deeply immersed in for the last two days: all their derivations, etc.” And to her son, John Julius Norwich, PLF writes: “Last year Jock Murray suddenly told me that about two hundred pounds had mounted up (in royalties) so I blew the lot on the DNB (Dictionary of National Biography) . . . so give me a few minutes notice and I can be pretty knowing about almost anyone in England – before 1900 – up to William Tytler (1711-1792) . . . it would be hard to find a more fascinating and time-wasting acquisition.” Both examples could be me to a T.

A Life In Letters is a delight, some parts reading like a travel book, other parts a glimpse into a vanished lifestyle, all of which is bound up with great friendships, anecdotal offerings and humour.

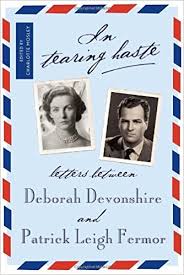

So, what will I read next? In Tearing Haste, edited by Charlotte Mosley, was one of PLF’s last projects and is a compilation of the letters exchanged between himself and Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire, over the course of a friendship that spanned more than forty years. However, having already read this when it was first published, I’m thankful that Patrick Leigh Fermor has led me to another possibility, as so often happens with the best books –

From a letter to Lawrence Durrell, November 1954 –

“. . . I’ve just got . . . Daphne’s (5) autobiography Mercury Presides . . . . which is rattling, splended stuff, not a bit the niminy-piminy society memoir you would think, but hell for leather, a mixture of lyrical charm and touchingness with a clumsy, rustic tough edge to it which is most engaging and terribly funny. Rather like the letters of Lady Bessborough or Caroline Lamb, half-sylph, half-stablehand.”

Leave a comment below in order to be entered

Leave a comment below in order to be entered

into a drawing to win a copy of this book!

- Rumanian Princess Anne-Marie Callimachi.

- Greek photographer Costa Achillopoulos.

- Arturo Lopez-Willshaw, Chilean millionaire.

- Judith Anne Dorothea Blunt-Lytton, whose mother had been Byron’s granddaughter.

- Daphne Fielding, formerly Marchioness of Bath.