by Kristine Hughes Patrone

If you’d been watching Season 2, Episode 4 of the PBS Masterpiece series Victoria, you would have seen Prince Albert addressing the problem of the outdated, and stinking, drains at Buckingham Palace. In reality, the problem of outdated and overburdened drains extended far beyond the Palace and permeated through the entire city of London. So prevalent was the problem that it came to be known as The Great Stink, a condition once so grave that it’s remediation has gone down in history as one of the greatest engineering feats of its day.

The Great Stink actually took place in 1858, but of course London had been stinking for centuries prior. In the first half of the 19th Century, London’s population was 2.5 million, all of whom ultimately discharged their waste directly onto the streets or into the Thames. Besides people, there were hundreds of thousands of horses, cows, dogs, cats, sheep, etc. adding their daily contributions to the waste problem. John Cadbury, social reformer and candy company founder, wrote: “Foul odors emanated from more than 200,000 cesspools across London, in alleyways, yards, even the basements of houses. It was not a smell that could be easily washed away.”

Most homes and businesses were built above cesspits, designed to drain to the street by means of a crudely built culvert to a partially open sewer trench in the center of the street. The design was faulty, to say the least. Cesspits often overflowed and waste soaked foundations, walls and floors of living quarters. Culverts typically became blocked and caused sewage to spread under buildings and contaminate shallow wells, cisterns and water ways from which drinking water was drawn. In October 1660, Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary: “Going down to my cellar…I put my feet into a great heap of turds, by which I find that Mr. Turner’s house of office is full and comes into my cellar.

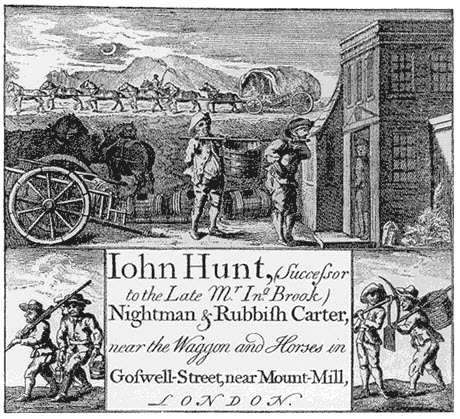

While causing disgust in Pepys and thousands of other Londoners, cesspits gave work to a portion of the population who included night soil men and saltpetre men. Saltpetre is another name for potassium nitrate, an essential ingredient in the manufacture of gunpowder. It was typically generated by collecting vegetable and animal waste into heaps and mixing it with limestone, mortar, earth and ashes. These heaps were kept moist from time to time with urine or other waste from stables. Digging for ingredients in outbuildings such as dovecotes and stables provided adequate supplies of gunpowder for the navy. Beginning during the reign of Elizabeth I, official saltpetre men were given powers to requisition any suitable deposits they came across. In 1621 James I appointed Lords of the Admiralty as Commissioners for Saltpetre and Gunpowder. They divided the country into districts for collection, and specialised saltpetre men were appointed and given weekly quotas to meet. They were also awarded powers with the right to enter premises to dig for nitrogenous earth.

In addition to saltpetre men, night soil men removed human waste that they then sold as fertilizer for crops. It was filthy job that involved crawling through cesspits and sewers or descending into them from ladders. Henry Mayhew describes them in his London Labour and the London Poor. You can read it here.

By 1810, the city’s one million inhabitants had to be content with 200,000 cesspits. The pressure on these and the haphazard sewer system caused the pits to overflow into street drains designed originally to cope with rainwater, but now also used to carry waste from factories, slaughterhouses and other activities, contaminating the city before emptying into the River Thames, or into the old London streams – the Fleet, the Wandle, the West Bourne, the Ravensbourne, the New, the Holbourne and many others that had been partially covered. WC’s discharged human waste directly into these streams and as most of those on the south side were tide-locked and drained into the Thames only at low tide, the results were catastrophic – much of London’s drinking water was still being extracted from the Thames, often downstream from the sewage discharge points.

Whilst the government and various commissioners and officials put forth plans for cleaning up London’s cesspits and sewers, the Duke of Wellington forged ahead with action of his own at the Tower of London – he was Constable of the Tower for 26 years. Centuries before, latrines and been built and desgined to empty directly into the moat set into the outer wall of Edward I’s Brass Mount in the north-eastern corner of the Tower. In addition, the moat connected to the River Thames, which washed its foul and putrid self about the Tower at both high and low tide. In 1830, the Duke of Wellington ordered the silt from the moat be taken to fertilize market gardens at Battersea, but this was not enough to prevent complaints in 1841 that the banks exposed at low tide were ‘impregnated with putrid animal and excrementitious matter … emitting a most prejudicial smell,’ resulting in 80 men from the garrison being taken to hospital. Wellington ordered the moat to be completely drained and covered over, the work being completed in 1845.

Dire problems with London’s water supply inevitably took their toll on the City’s inhabitants – cholera first struck London in 1832 and again in 1840. In 1854 London physician Dr John Snow discovered that the disease was transmitted by drinking water contaminated by sewage after an epidemic broke out in Soho, but this idea was not widely accepted even by that late date.

The lawyer Edwin Chadwick, secretary to the Poor Law Commision, was one of many to draw attention to London’s unsanitary living conditions. In 1842, he produced an uncompromising and influential paper, ‘The Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain.’ Shocked by the squalor of the slums, he cited ‘atmospheric impurities produced by decomposing animal and vegetable substances,’ ‘damp and filth,’ and ‘close and overcrowded dwellings” as leading inevitably to disease and epidemics. Chadwick enlisted the aid of Charles Dickens, who personally recorded graphic accounts of the terrible state of reeking graveyards from his brother-in-law, Henry Austin, a leading sanitary reformer.

However, attempts at sanitary clean up were slow, as this letter to the editor of The Times – written in 1849 – shows –

TO THE EDITUR OF THE TIMES PAPER

Nearly a decade later, the situation had hardly improved. The year 1858 saw an exceptionally hot summer, over the course of which the Thames and many of its urban tributaries continued to overflow with sewage. Bacteria grew and the miasma of noxious smells increased until even the members of the House of Commons couldn’t ignore it, being driven out of the House by the foul odours. A House of Commons select committee was appointed to report on the Stink and recommend solutions and within 18 days a bill was passed into law that provided the funds necessary for a comprehensive sewer scheme for London, and to build the Embankment along the Thames in order to improve both the flow of water and of traffic.

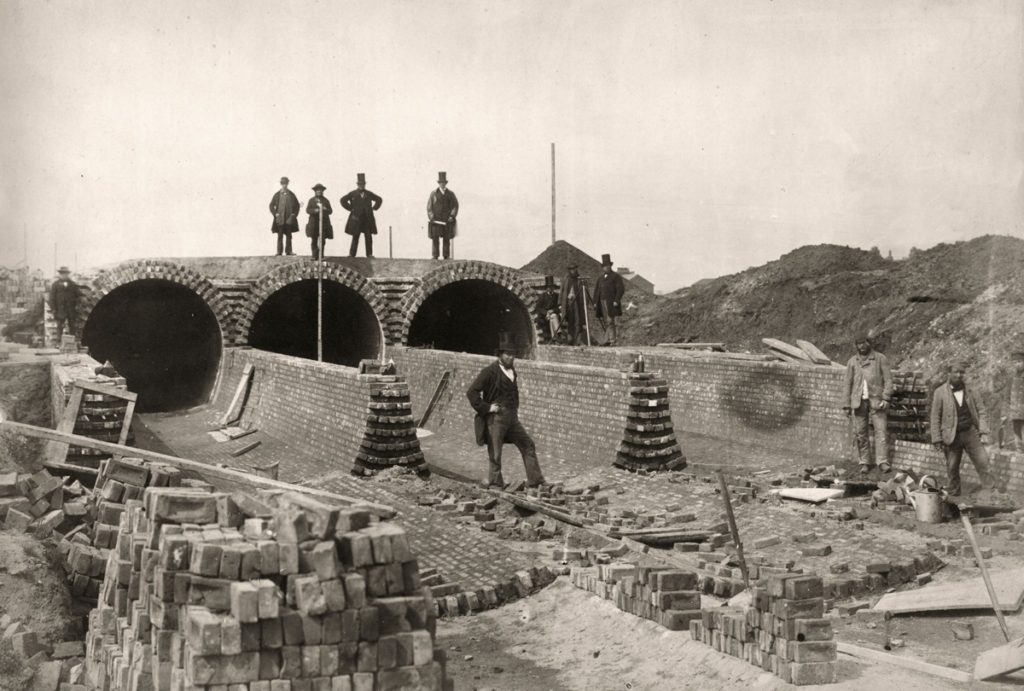

In 1855 the Metropolitan Board of Works which, after rejecting many schemes for “merciful abatement of the epidemic that ravaged the Metropolis”, accepted a scheme to implement sewers proposed in 1859 by its chief engineer, Joseph Bazalgette. The intention of this very expensive scheme was to resolve the epidemic of cholera by eliminating the stench which was believed to cause it.

Massive sewers were built running along the north and south banks of the river Thames. These captured the waste that would otherwise pour into the river. The sewers gently inclined downwards to the east, resulting in the waste flowing towards the sea. In areas such as Victoria, the muddy foreshore was reclaimed, and sewers and the new underground railway were installed. On the surface, a 30 metre width of landscaped road and pavement was established, providing a modern and elegant

boulevard now known as the Embankment, which also served to guard against flooding. These new sewers terminated at pumping stations east of London in Kent and Essex, where the waste was carried out to sea on the outgoing tide. The Prince of Wales opened the pumping station at Crossness in Kent in 1865.

Work on London’s massive new sewer system continued over the next six years and, eventually the “Great Stink” became but a thing of memory, as did cholera.

Thames Water has produced a film about the construction of the sewer, which you can watch here.