Category: Duke of Wellington

A Couple In England – Day Three – Part Three

A Couple In England – Day Three -Part Two

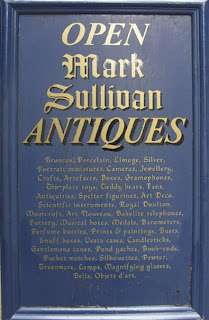

Wellington Miniature at Auction

A portrait of the Field Marshall Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, by Robert Thorburn is on sale with Bonhams at Knightsbridge on 21st November (estimate £3000 – 4000). Angela Burdett-Coutts, an avid collector of portrait miniatures, allegedly commissioned this piece by Thorburn. At the age of 32 she proposed to the Duke depicted in this image, having fallen deeply in love with this legendary military hero.

Forty-five years her senior, Wellesley gently refused her advances with her best interests at heart. He stated in a letter to her that he could still act as her ‘Friend, Guardian, Protector’, offering a hand of friendship to soothe the affections he felt were misdirected to a man of his age.

Jennifer Tonkin, Specialist in the Portrait Miniatures department, said, “We’re delighted to be able to include this rare image of Arthur Wellesley that derives from a very important group portrait by Thorburn of staggering proportions.

The unrequited love story behind the commissioning of lot 127 seems to highlight the Duke’s fragility in this reduced composition and it is possible that potential bidders will be as responsive to the link with Angela Burdett-Coutts as they are to Thorburn’s masterly technique.”

This miniature of the Duke sits alongside other notable lots in the auction, such as Richard Cosway’s depiction of the Muse Thalia rumored to be modeled for by Lady Emma Hamilton (estimate £3000 – 5000). Thorburn’s work is a masterful image with an endearing story and this miniature portrait is set to add color to a fascinating sale. The entire auction catalogue of miniatures can be found here.

Trading in Death – Wellington

Saturday, November 27th 1852

(The Duke died on 14 September 1852; his State Funeral took place on November 18)

Several years have now elapsed since it began to be clear to the comprehension of most rational men, that the English people had fallen into a condition much to be regretted, in respect of their Funeral customs. A system of barbarous show and expense was found to have gradually erected itself above the grave, which, while it could possibly do no honor to the memory of the dead, did great dishonor to the living, as inducing them to associate the most solemn of human occasions with unmeaning mummeries, dishonest debt, profuse waste, and bad example in an utter oblivion of responsibility. The more the subject was examined, and the lower the investigation was carried, the more monstrous (as was natural) these usages appeared to be, both in themselves and in their consequences. No class of society escaped. The competition among the middle classes for superior gentility in Funerals—the gentility being estimated by the amount of ghastly folly in which the undertaker was permitted to run riot—descended even to the very poor: to whom the cost of funeral customs was so ruinous and so disproportionate to their means, that they formed Clubs among themselves to defray such charges.

Many of these Clubs, conducted by designing villains who preyed upon the general infirmity, cheated and wronged the poor, most cruelly; others, by presenting a new class of temptations to the wickedest natures among them, led to a new class of mercenary murders, so abominable in their iniquity, that language cannot stigmatize them with sufficient severity. That nothing might be wanting to complete the general depravity, hollowness, and falsehood, of this state of things, the absurd fact came to light, that innumerable harpies assumed the titles of furnishers of Funerals, who possessed no Funeral furniture whatever, but who formed a long file of middlemen between the chief mourner and the real tradesman, and who hired out the trappings from one to another —passing them on like water-buckets at a fire —every one of them charging his enormous percentage on his share of the “black job.” Add to all this, the demonstration, by the simplest and plainest practical science, of the terrible consequences to the living, inevitably resulting from the practice of burying the dead in the midst of crowded towns; and the exposition of a system of indecent horror, revolting to our nature and disgraceful to our age and nation, arising out of the confined limits of such burial-grounds, and the avarice of their proprietors; and the culminating point of this gigantic mockery is at last arrived at.

Out of such almost incredible degradation, saving that the proof of it is too easy, we are still very slowly and feebly emerging. There are now, we confidently hope, among the middle classes, many, who having made themselves acquainted with these evils through the parliamentary papers in which they are described, would be moved by no human consideration to perpetuate the old bad example ; but who will leave it as their solemn injunction on their nearest and dearest survivors, that they shall not, in their death, be made the instruments of infecting, either the minds or the bodies of their fellow-creatures. Among persons of note, such examples have not oeen wanting. The late Duke of Sussex did a national service when he desired to be laid, in the equality of death, in the cemetery of Kensal Green, and not with the pageantry of a State Funeral in the Boyal vault at Windsor. Sir Robert Peel requested to be buried at Drayton. The late Queen Dowager left a pattern to every rank in these touching and admirable words. “I die in all humility, knowing well that we are all alike before the Throne of God; and I request, therefore, that my mortal remains be conveyed to the grave without any pomp or state. They are to be removed to St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, where I request to have as private and quiet a funeral as possible. I particularly desire not to be laid out in state. I die in peace and wish to be carried to the tomb in peace, and free from the vanities and pomp of this world I request not to be dissected or embalmed, and desire to give as little trouble as possible.”

With such precedents and such facts fresh in the general knowledge, and at this transition time in so serious a chapter of our social history, the obsolete custom of a State Funeral has been revived, in miscalled “honor” of the late Duke of Wellington. To whose glorious memory be all true honor while England lasts!

We earnestly submit to our readers that there is, and that there can be, no kind of honor in such a revival; that the more truly great the man, the more truly little the ceremony ; and that it has been, from first to last, a pernicious instance and encouragement of the demoralising practice of trading in Death.

It is within the knowledge of the whole public, of all diversities of political opinion, whether or no any of the Powers that be, have traded in this Death—have saved it up, and petted it, and made the most of it, and reluctantly let it go. On that aspect of the question we offer no further remark.

But, of the general trading spirit which, in its inherent emptiness ana want of consistency and reality, the long-deferred State Funeral has appropriately awakened, we will proceed to furnish a few instances all faithfully copied from the advertising columns of The Times.

First, of seats and refreshments. Passing over that desirable first-floor where a party could be accommodated with ” the use of a piano”; and merely glancing at the decorous daily announcement of “The Duke of Wellington Funeral Wine,” which was in such high demand that immediate orders were necessary; and also ” The Duke of Wellington Funeral Cake,” which “delicious article could only be had of such a baker; and likewise “The Funeral Life Preserver,” which could only be had of such a tailor; and further “the celebrated lemon biscuits,” at one and fourpence per pound, which were considered by the manufacturer as the only infallible assuagers of the national grief; let us pass in review some dozen of the more eligible opportunities the public had of profiting by the occasion.

LUDGATE HILL.—The fitting, and arrangements for viewing this grand and Solemnly imposing procession are now completed at this establishment, and those who are desirous of obtaining a fine and extensive view, combined with every personal convenience and comfort, will do well to make Immediate inspection of the SEATS now remaining on hand.

FUNERAL, including Beds the night previous.— To be LET, a SECOND FLOOR, of three rooms, two windows, having a good view of the procession. Terms, including refreshment, 10 guineas. Single places, Including bed and breakfast, from 16*.

THE DUKE’S FUNERAL.—A first-rate VIEW for 15 persons, also good clean beds and a sitting-room on reasonable terms.

FUNERAL of tlie late Duke of WELLINGTON.— To be LET, a SECOND FLOOR, two windows, firing and every convenience. Terms moderate for a party. Also a few seats in front, one guinea each. Commanding a view from Piccadilly to Pall-Mall

FUNERAL of the DUKE of WELLINGTON.— The FIRST and SECOND FLOORS to be LET, either by the room or window, suited to gentlemen’s families, for whom every comfort and accommodation will be provided, and commanding the very best view of this imposing spectacle. The ground floor is also fitted up with commodious seats, ranging in price from one guinea. Apply on the premises.

THE DUKE’S FUNERAL.—Terms very moderate. —TWO FIRST FLOOR ROOMS, with balcony and private entrance out of the Strand. The larger room capable of holding 15 persons. The small room to be let for eight guineas.

THE

DUKE’S FUNERAL. —To be LET, in SHOP WINDOW, with seats erected for about 80, for 25 guineas. Also a Furnished First Floor, with two large windows. One of the best views in the whole range from Temple-bar to St. Paul’s. Price 36 guineas. A few single seats one guinea each.

THE FUNERAL PROCESSION of the DUKE of WELLINGTON. — Cock spur-street, Charing-cross, decidedly the best position in the whole route, a few SEATS still DISENGAGED, which will be offered at reasonable prices. An early application is requisite, as they are fast filling up. Also a few places on the roof. A most excellent view.

FUNERAL of the Late DUKE of WELLINGTON.—To be LET, in the best part of the Strand, a SECOND FLOOR, for £10; a Third Floor, £7 10*, containing two windows in each: front seats in shop, at one guinea.

THE DUKE’S FUNERAL.—To be LET, for 85 guineas to a genteel family, In one of the most commanding situations in the line of route, a FIRST FLOOR, with safe balcony, and ante-room. Will accommodate 20 persons, with an uninterrupted and extensive view for all. For a family of less number a reduction will be made. Every accommodation will be afforded.

But above all let us not forget the

NOTICE TO CLERGYMEN.—T. C. Fleet-street, it has reserved for clergymen exclusively, upon condition only that they appear in their regalia, FOUR FRONT SEATS, at £1 each; four second tier, at 16 each; four third tier, at 12. 6.; four fourth tier, at 10; four fifth tier.

The anxiety of this enterprising tradesman to get up a reverend tableau in his shopwindow of fourand-twenty clergymen all on six rows, is particularly commendable, and appears to us to shed a remarkable grace on the solemnity.

These few specimens are collected at random from scores upon scores of such advertisements, mingled with descriptions of non-existent ranges of view, and with, invitations to a few agreeable gentlemen who are wanted to complete a little assembly of kindred souls, who have laid in abundance of “refreshments, wines, spirits, provisions, fruit, plate, glass, china,” and other light matters too numerous to mention, and who keep “good fires.” On looking over them we are constantly startled by the words in large capitals, ” Would To God Night Or Blucher Were Come! “which, referring to a work of art, are relieved by a legend setting forth how the lamented hero observed of it, “in his characteristic manner, ‘ Very good; very good indeed.'”

Then, autographs fall into their place in the State Funeral train. The sanctity of a seal, or the confidence of a letter, is a meaningless phrase that has no place in the vocabulary of the Traders in Death. Stop, trumpets, in the Dead March, and blow to the world how characteristic we autographs are !

WELLINGTON AUTOGRAPHS.—TWO consecutive LETTERS of the DUKE’S (1843) highly characteristic and authentic, with the Correspondence, that elicited them, the whole forming quite a literary curiosity, for £15.

WELLINGTON AUTOGRAPHS.—To be DISPOSED OF, TWO AUTOGRAPH LETTERS of the DUKE of WELLINGTON, one dated Walmer Castle, 9th October, 1831, the other London, 17th May, 1843, with their post-marks and seals.

WELLINGTON. —THREE original NOTES, averaging 2 pages each, (not lithographs,) seal, and envelopes, to be SOLD. Supposed to be the most characteristic of his Grace yet published. The highest sum above £30 for the two, or £20 for the one.

FM. the DUKE of WELLINGTON.—To be SOLD, by a member of the family, to whom It was written, an ORIGINAL AUTOGRAPH LETTER of the ate Duke of Wellington, on military affairs, six pages long, in the best preservation. Price £30.

FIELD-MARSHAL the DUKE of WELLINGTON’S AUTOGRAPH.—A highly characteristic LETTER of the DUKE’S for DISPOSAL, wherein he alludes to his living 100 years, date 1847, with envelope. Seal, with crest perfect. £10 will be taken.

DUKE of WELLINGTON.—An AUTOGRAPH LETTER of the DUK E, written Immediately after the death of the Duchess In 1831, Is for SALE; also Two Autograph Envelopes franked and sealed.

DUKE of WELLINGTON. — AUTOGRAPH BUSINESS LETTER, envelope, seal, post-mark, etc. complete. Style courteous and highly characteristic. Will be shown by the party and at the place addressed. Price £15.

FIELD-MARSHAL the DUKE of WELLINGTON. —TWO AUTOGRAPH LETTERS of His Grace, one in his 61st, the other in his 72d year, both first-rate of his characteristic graphic style, and on Their genuineness can be subject, to be SOLD.

THE DUKE of WELLINGTON.—A very curious DOCUMENT, partly printed, and the rest written by His Grace to a lady. This is well worthy of A place in the cabinet of the curious. There is nothing like It. Highest offer will be taken.

TO be SOLD, SIX AUTOGRAPH LETTERS from F.M.the Duke of WELLINGTON, with envelopes and seals, which have been generously given to aid a lady in distressed circumstances.

THE DUKE of WELLINGTON.—A lady has in her possession a LETTER, written by his Grace on the 18th of June, in the present year, and will be happy to DISPOSE OF the same. The letter is rendered more valuable by its being written on the last anniversary which his Grace was spared to celebrate. The letter bears date from Apsley House, with perfect envelope and seal.

A CLERGYMAN has TWO LETTERS, with Envelopes, addressed to him by the late DUKE, and bearing striking testimony to the extent of his Grace’s private charities, to be DISPOSED OF at the highest offer (for one or both), received by the 18th Instant. The offers may be contingent on further particulars being satisfactory.

THE DUKE of WELLINGTON.—A widow, in deep distress, has in her possession an AUTOGRAPH LETTER of his Grace the Duke of WELLINGTON, written In 1830, enclosed and directed in an envelope, and sealed with his ducal coronet, which she would be happy to PART WITH for a trifle.

VALUABLE AUTOGRAPH NOTE of the late Duke of WELLINGTON, dated March 27, 1860, to be SOLD, for £20, by the gentleman to whom it was addressed together with envelope, perfect impression of Ducal seal, and Knightsbridge post-mark distinct. The whole in excellent preservation. A better specimen of the noble Duke’s handwriting and highly characteristic style cannot be seen.

ONE of the last LETTERS of the DUKE of WELLINGTON for DISPOSAL, dated from Walmer Castle within a day or two of his death, highly characteristic, with seal and post-marks distinct. This being probably the last letter written by the late Duke its interest as a relic must be greatly enhanced. The highest offer accepted. May be seen on application.

THE GREAT DUKE.—A LETTER of the GREAT HERO, dated March 27, 1351, to be SOLD. Also a beantiful Letter from Jenny Lind, dated June 10, 1862. The highest offer will be accepted. Address with offers of price.

Miss Land’s autograph would appear to have lingered in the shade until the Funeral Train came by, when it modestly stepped into the procession and took a conspicuous place. We are in doubt which to admire most; the ingenuity of this little stroke of business; or the affecting delicacy that sells “probably the last letter written by the late Duke” before the aged hand that wrote it under some manly sense of duty, is yet withered in its grave ; or the piety of that excellent clergyman—did he appear in his surplice in the front row of T. C.’s shop-window?—who is so anxious to sell “striking testimony to the extent of His Grace’s private charities;” or the generosity ot that Good Samaritan who poured ” six letters with envelopes and seals “into the wounds of the lady in distressed circumstances.”

Lastly come the relics—precious remembrances worn next to the bereaved heart, like Hardy’s miniature of Nelson, and never to be wrested from the advertisers but with ready money.

MEMENTO of the late DUKE of WELLINGTON. —To be DISPOSED OF, a LOCK of the late Illustrious DUKE’S HAIR. Can be guarant

eed. The highest offer will be accepted. Apply by letter prepaid.

THE DUKE of WELLINGTON. —A LOCK ot HAIR of the late Duke of WELLINGTON to be DISPOSED OF, now in the possession of a widow lady Cut off the morning the Queen was crowned. Apply by letter post paid.

VALUABLE RELIC of the late DUKE of WELLINGTON.—A lady, having in her possession a quantity of the late illustrious DUKE’S HAIR, cut in 1841, is willing to PART WITH a portion of the Same for £25. Satisfactory proof will be given of its identity, and of how it came into the owner’s possession, on application by letter, pre-paid.

RELIC of the DUKE of WELLINGTON for SALE- The son of the late well-known haircutter to his Grace the Duke of Wellington, at Strathfieldsaye, has a small quantity of HAIR, that his father cut from the Duke’s head, which he is willing to DISPOSE OF. Any one desirous of possessing such a relic of England s hero are requested to make their offer for the same, by letter.

RELICS of the late DUKE of WELLINGTON.— For SALE, WAISTCOAT, In good preservation, worn by his Grace some years back, which can be well authenticated as such.

Next, a very choice article—quite unique— the value of which may be presumed to be considerably enhanced by the conclusive impossibility of its being doubted in the least degree by the most suspicious mind.

A MEMENTO of the DUKE of WELLINGTON.— La Mort de Napoleon. Ode d’Alcxandre Manzoni, avec la Traduction en Francais, par Edmond Angelini.—A book, in which the above is the title, was torn up by the Duke and thrown by him from the carriage, in which he was riding, as he was passing through Kent: the pieces of the book were collected and put together by a person who saw the Duke tear it and throw the same away. Any person desirous of obtaining the above memento will be communicated with.

Finally, a literary production of astonishing brilliancy and spirit; without which, we are authorized to state, no nobleman’s or gentleman’s library can be considered complete.

DUKE of WELLINGTON and SIR R. PEEL.— A talented, interesting, and valuable WORK, on Political Economy and Free Trade, was published in 1830, and immediately bought up by the above statesmen, except one copy, which is now for DISPOSAL. Apply by letter only.

Here, for the reader’s sake, we terminate our quotations. They might easily have been extended through the whole of the present number of this Journal.

We believe that a State Funeral at this time of day—apart from the mischievously confusing effect it has on the general mind, as to the necessary union of funeral expense and pomp with funeral respect, and the consequent injury it may do to the cause of a great reform most necessary for the benefit of all classes of society—is, in itself, so plainly a pretence of being what it is not: is so unreal, such a substitution of the form for the substance: is so cut and dried, and stale: is such a palpably got up theatrical trick: that it puts the dread solemnity of death to flight, and encourages these shameless traders in their dealings on the very coffin-lid of departed greatness. That private letters and other memorials of the great Duke of Wellington would still have been advertised and sold, though he had been laid in his grave amid the silent respect of the whole country with the simple honors of a military commander, we do not doubt; but that, in that case, the traders would have been discouraged from holding anything like this Public Fair and Great Undertakers’ Jubilee over his remains, we doubt as little. It is idle to attempt to connect the frippery of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office and the Herald’s College, with the awful passing away of that vain shadow in which man walketh and disquieteth himself in vain. There is a great gulf set between the two which is set there by no mortal hands, and cannot by mortal hands be bridged across. Does any one believe that, otherwise, “the Senate” would have been “mourning its hero” (in the likeness of a French Field-Marshal) on Tuesday evening, and that the same Senate would have been in fits of laughter with Mr. Hume on Wednesday afternoon when the same hero was still in question and unburied.

The mechanical exigencies of this journal render it necessary for these remarks to be written on the evening of the State Funeral. We have already indicated in these pages that we consider the State Funeral a mistake, and we hope temperately to leave the queation here for temperate consideration. It is easy to imagine how it may have done much harm, and it is hard to imagine how it can have done any good. It is only harder to suppose that it can have afforded a grain of satisfaction to the immediate descendants of the great Duke of Wellington, or that it can reflect the faintest ray of lustre on so bright a name. If it were assumed that such a ceremonial was the general desire of the English people, we would reply that that assumption was founded on a misconception of the popular character, and on a low estimate of the general sense; and that the sooner both were better appreciated in high places, the better it could not fail to be lor us all. Taking for granted at this writing, what we hope may be assumed without any violence to the truth; namely, that the ceremonial was in all respects well conducted, and that the English people sustained throughout, the high character they have nobly earned, to the shame of their silly detractors among their own countrymen; we must yet express our hope that State Funerals in this land went down to their tomb, most fitly, in the tasteless and tawdry Car that nodded and shook through the streets of London on the eighteenth of November, eighteen hundred and fifty-two. And sure we are, with large consideration for opposite opinions, that when History shall rescue that very ugly machine—worthy to pass under decorated Temple Bar, as decorated Temple Bar was worthy to receive it—from the merciful shadows of obscurity, she will reflect with amazement — remembering his true, manly, modest, self-contained, and genuine character—that the man who, in making it the last monster of its race, rendered his last enduring service to the country he had loved and served so faithfully, was Arthur Duke of Wellington.