LOUISA CORNELL

The thing about taverns, also known as public houses and now known by the shortened PUB, is that much of a community’s life was lived there. Every aspect of life was celebrated at the local tavern. Every type of business, legal and illegal, was conducted there. And every sort of relationship, passionate or cold, toxic or sweet, loving or murderous was often played out in the local tavern. With so much of life taking place in these microcosms of London, one cannot be surprised that the energy – good or bad, mad or sane, saintly or evil – has lingered long after those who lived these events and emotions are gone. Don’t believe me? The next time you are fortunate enough to be in London, stop by these locals, if you dare!

TOWN OF RAMSGATE

WAPPING

62 Wapping High Street

London

Should you decide to explore the alleyway to the side of the pub that leads to the Wapping Old Stairs you might encounter the local ghost, a ghost the Thames Police have reported seeing to this day. Judge George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys, (15 May 1645 – 18 April 1689) rose to prominence during the reign of James II. He became Lord Chief Justice and eventually Lord Chancellor. His loyalty to the king was without question. However, after Monmouth’s Rebellion in 1685 he was sent to the West Country to conduct the trials of those rebels who participated in the rebellion. He gained a reputation for his abuse of the attorneys of the accused, his sometimes biased application of the law and his tendency to hand out death sentences like drinks at a political rally. He became the most feared and hated judge in England.

After James II fled England and William and Mary ascended the throne, Jeffreys waited to long to follow his king to the Continent. In 1688 he disguised himself as a sailor, shaved his distinctive bushy brows, and waited at the Town of Ramsgate to catch a ship. Unfortunately, a victim of his cruelty – either an accused rebel or an attorney for same recognized the judge. He was captured by a mob at the Town of Ramsgate and narrowly missed being hanged at the top of the Wapping Stairs. He was taken to the Tower of London and died there of kidney failure in 1689.

It is said his ghost can be seen leaving the pub and trying to take the stairs down to the docks to meet the ship he missed, ever looking over his shoulder in search of the angry mob that captured him so long ago.

THE COCKPIT

BLACKFRIARS

7 St. Andrew’s Hill

London

As with all tales of gambling and blood sports, it is rumored The Cockpit is visited from time to time by the ghost of a lady who is seen wringing her hands over her lack of money because of her husband’s gambling debts. The story is she made the mistake of following him to The Cockpit to prevent him from placing yet another bet. Unfortunately the man was in serious need of anger management. He supposedly beat her to death in the cellar of the pub or in the alley just outside the cellar doors and went back to the cockfight as if nothing had happened. On dark and quiet nights one is said to be able to hear their final confrontation and to catch the poor lady bemoaning her fate.

THE SPANIARDS INN

HAMPSTEAD HEATH

Spaniards Road

London

www.caughtinpixels.com

Why yes, there are several associated with the Spaniards. One is cautioned not to walk across the Heath from Kenwood House to the inn, especially at night, as one might be overtaken by Dick Turpin and Black Bess as they race for their favorite safe house. Sometimes, if one stands in front of the inn late at night and listens carefully one will Black Bess’s hoof beats on the road. Some even claim to have seen her in the car park on moonlit nights. Of course, the ghost of Juan Porero, killed by his brother in a duel over a woman and buried in the inn’s garden, is said to haunt the tavern as well. The ghost of a devious local money lender named Black Dick, run down by a coach in the inn yard, is said to tug the sleeves of patrons drinking at the bar. And a woman in a flowing white gown is said to have been seen crossing Hampstead Heath to come to the inn in search of her lover, a highwayman who never arrived for their last assignation.

THE GOLDEN LION

ST. JAMES

23 King Street – London

The Golden Lion comes with its own ghost, a barmaid murdered there in the early 19th century is said to prowl the stairs to the theatre bar in search of her murderer.

THE RISING SUN

CITY OF LONDON

38 Cloth Fair – London

Close to Smithfield Meat Market, The Rising Sun dates back to the early 17th century, when it was originally called the Starre Tavern. Around 200 years later the pub acquired a rather grisly history. This was the time of ‘body-snatching’ when there was a market for fresh bodies for dissection and medical research. Once all the graves had been depleted, to fill the demand for bodies the body-snatchers turned their attention to real-life victims. People began disappearing from local taverns – where they were drugged and then later murdered – and it’s said that two men, John Bishop and Thomas Williams, earmarked innocent drinkers at the Rising Sun and other nearby pubs, perhaps due to their proximity to St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Indeed, the evil pair are said to have sold up to 1000 bodies to anatomists. Little surprise, therefore, that The Rising Sun is no stranger to the supernatural, with employees hearing the sound of running footsteps and feeling ghostly presences. While two employees who lived above the pub have said that a spirit would regularly pull the duvet off their bed, one former landlady felt an icy-cold hand run down her back when she was showering.

THE HOOP AND TOY

SOUTH KENSINGTON

34 Thurloe Place

London

The oldest tavern in Kensington, dating back some 500 years. When the nearby tube station was being built, while boring a tunnel, construction workers accidentally unearthed the pub’s cellar which was found to contain the bound bodies of several dead priests. It’s said they woke these souls and since that fateful day, phantom priests have been spotted around the pub, especially on the stairs, which they’re said to be using as an alternative route back to their places of worship.

THE FLASK

HIGHGATE

77 Highgate West Hill

London

The Flask dates back to 1663 It also boasts not one but two ghosts: a Spanish barmaid who hanged herself in the pub’s cellar (now a seating area) over unrequited love, and a man in Cavalier uniform who likes to appear in the main bar every now and then. Staff and patrons have reported glasses moving of their own accord, lights swaying without explanation and temperature drops. To add to its grisly past, the pub’s Committee Room is said to have witnessed one of the first ever autopsies, performed during the days of grave-robbing from Highgate Cemetery.

THE WORLD’S END

CAMDEN

174 Camden High Street

London

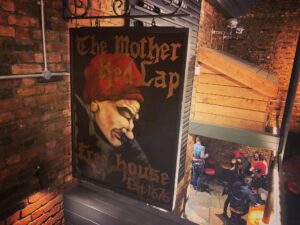

This pub has been a North London landmark for hundred of years. Though there are records of a tavern in the area as early as 1690, it wasn’t until the late 18th century that the Mother Red Cap (as the pub was formerly known) Legend has it that the pub is on the site of a cottage belonging to the witch Old Mother Red Cap (hence its former name). Known to practice black magic, it’s said that when she died, the devil entered her home and never left. Though no apparitions have been seen, shrieks have been heard from down below, though these could also be from the torture chambers and gallows allegedly once located in the basement.

The dark hauntings said to happen in The World’s End can possibly be traced back to a local woman, Jennie Bingham, or as she was known in the area, Mother Red Cap. Mother Red Cap, was a nickname given to a woman for one of two reasons, either as a landlord. Or, it’s more sinister reason, because a woman was a witch. And Jennie Bingham may have been both.

In life, Bingham, whose cottage stood on the site in the 17th century where the club now stands. She was known to live a life very few women would have dared to live especially in those days. She smoked, cursed like a shipwrecked sailor and reportedly had numerous lovers. Bingham, was also suspected of being in league with Lucifer and a poisoner of those she disliked. Back in the 17th century such charges could bring swift justice and the death penalty if proven.

According to legend, when Jennie Bingham was on her deathbed, Satan appeared at her bedside to collect her soul. However, it appears the devil did not get his due, as the troubled soul of Jennie Bingham is believed to haunt The World’s End.

Loud screams and blood curdling shrieks have been heard throughout The World’s End. Loud bangs and footsteps are commonly heard by staff as they open for the day or close at night. The angry wraith of Jennie Bingham has been witnessed by both staff and patrons lurking about the club. She has been known to rush those unfortunate enough to see her and scream curses into their faces.

THE TEN BELLS

SPITALFIELDS

Corner of Commercial Street and Fournier Street

London

The Ten Bells was a regular for a handful of Jack the Ripper’s victims before they met their gruesome end, including Annie Chapman, who was murdered after a night drinking in the pub. In an unrelated incident, one of the pub’s Victorian landlords was murdered with an axe and to this day, customers and staff claim to see his ghost wandering the upper floors.

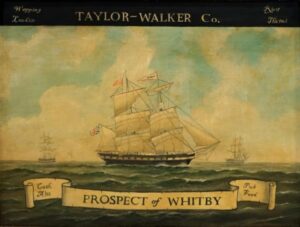

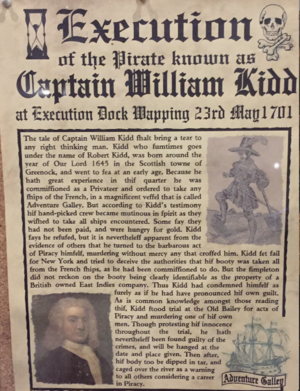

The most famous criminal hanged at the execution dock at the Prospect of Whitby was Captain William Kidd. Ironic, as the Scottish sea captain was originally appointed by the Crown to hunt down pirates. He discovered piracy was much more profitable than hunting down pirates. He did quite well for a while. Unfortunately, in 1698 he captured The Quedagh, which was sailing under a French pass. The captain, however, was an Englishman and the rich cargo Kidd took was property of the East India Company. Kidd was eventually captured and brought back to London where he was sentenced to death for piracy and for the murder of one of his own crewmen (in 1697) who had dared to cross him.

The most famous criminal hanged at the execution dock at the Prospect of Whitby was Captain William Kidd. Ironic, as the Scottish sea captain was originally appointed by the Crown to hunt down pirates. He discovered piracy was much more profitable than hunting down pirates. He did quite well for a while. Unfortunately, in 1698 he captured The Quedagh, which was sailing under a French pass. The captain, however, was an Englishman and the rich cargo Kidd took was property of the East India Company. Kidd was eventually captured and brought back to London where he was sentenced to death for piracy and for the murder of one of his own crewmen (in 1697) who had dared to cross him.