EXCERPT from LOST IN LOVE by LOUISA CORNELL

THE FOOL OF A BEAR baiter looked at her as if she had two heads.

“I mean it, you puffed up bully.” She flicked the whip at him and knocked the tattered hat from his head. “This dog belongs to Miss Worthy. Should you try to take him I shall horsewhip you within an inch of your life.” She stepped forward and raised the whip to prove her point.

“And I will take up where she leaves off,” Lucy declared. She handed Horatio’s lead to the menacing footman and pushed her sleeves up to her elbows.

“You’re both mad. I’ll teach you to strike me, you silly chit.” He raised his fist and might have hit Adelaide had two things not happened almost at once. She was lifted away from him. At the same time, a powerful hand shot out and knocked the man on his arse.

Marcus.

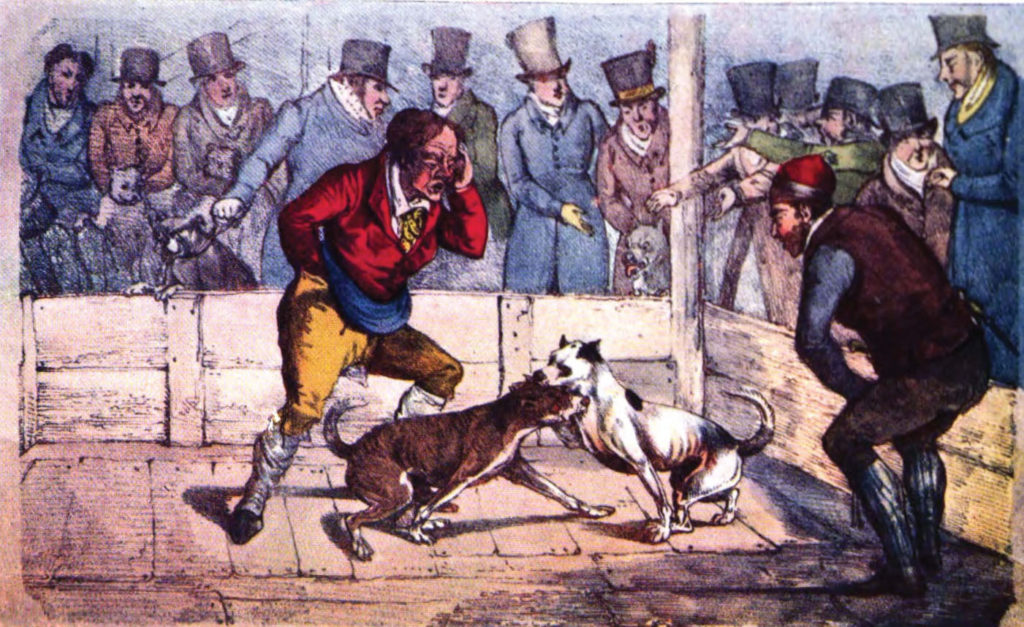

Her husband glared at the two ruffians who held the scarred dogs on leads. They retreated immediately. He stood over the barker, shaking with fury. “That chit is the Duchess of Selridge. My wife.” The man’s face paled noticeably. “If you value your life you will take this sideshow back to Bankside and never show your face to me again. Understood?”

The barker and his dog handlers nodded vigorously and made haste to do exactly as Marcus said. Adelaide found herself guided by an overbearing grip to her elbow as she was propelled back to the phaeton. The Earl of Creighton offered Lucy his arm and escorted her back towards the Serpentine, her footman and Horatio close behind her. Lucy waved, her face wreathed in concern.

Adelaide was suddenly snatched off her feet.

“Your leg.” The words of concern came out in a squeak as Marcus lifted her by the waist and deposited her with a short drop onto the bench seat. He climbed in beside her and, with a brief nod to the Earl of Creighton, started the grays toward the main gate of the park.

She looked back at the two dogs as the barker and his henchmen dragged them towards the crowd of young gentlemen. The dogs gazed at her forlornly. Their eyes said so much and it broke Adelaide’s heart. A horse and rider stepped out of a copse of oak trees. Dylan raised his hat to her in silent salute and then walked his horse in the direction of the barker, the dogs, and the crowd.

Adelaide turned to find her husband’s gaze fixed on Dylan’s back. She did not like the expression she saw there. When he turned his piercing green eyes on her, she liked it even less. She searched her mind for the words to cool that emerald fire. “Marcus, I realize I shouldn’t have—”

“We’ll talk about it when we get home, Adelaide. I’d rather not be involved in two scenes in Hyde Park in the same day, if it’s all the same to you.”

“Is there going to be a scene?” She tried to pass the question off as a jest.

“Oh, yes, madam. Count on it.”

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BEAR BAITING

and OTHER DOG FIGHTING “SPORTS”

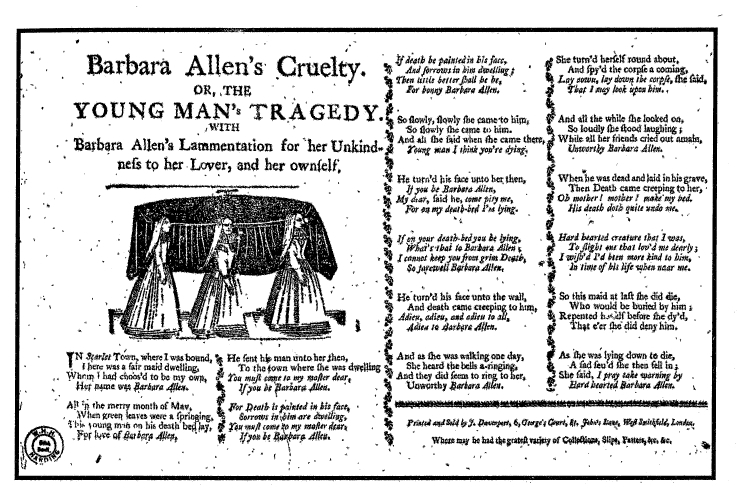

Most of the early forms of dog fighting involved baiting them with other animals. The most popular of these were bull-baiting and bear-baiting. The first record we have of a bull-baiting in England gives the date of 1209. The so-called sport lasted until the 19th century. Bull-baiting was actually required in the 17th century, as the theory was it tenderized the meat. As for the practice of baiting between dogs and monkeys, rats, ponies, and even lions—I am still trying to find a twisted justification for those events. I doubt I ever will.

Both dog fighting and cock fighting were considered gentlemen’s sports. The major spectators, therefore, were members of the aristocracy. Queen Elizabeth I enjoyed animal baiting and banned plays on Thursdays, as that was when most animal baitings took place. King James was also a fan and retired several mastiffs after they defeated a lion. He felt after they had defeated a lion, any other opponent would be beneath them. Dogs fighting each other was established as a sport by the mid-17th century and was legal in England through the mid-1800’s. Some owners of fighting dogs were indeed gentlemen and members of the peerage, but the sport also became popular among the working class as well.

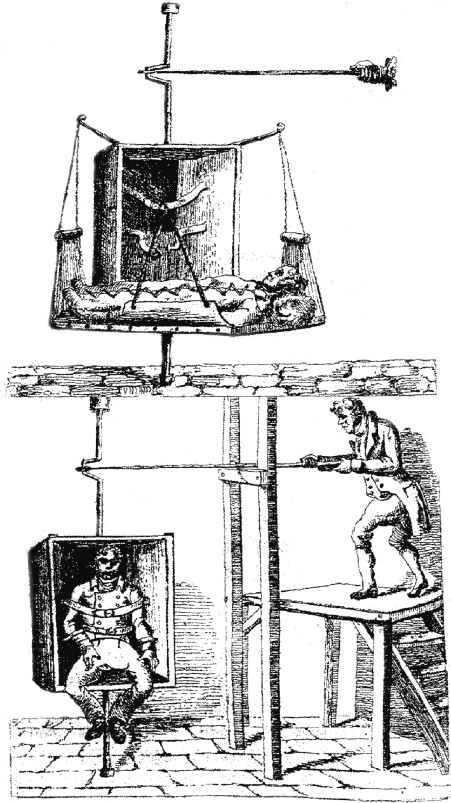

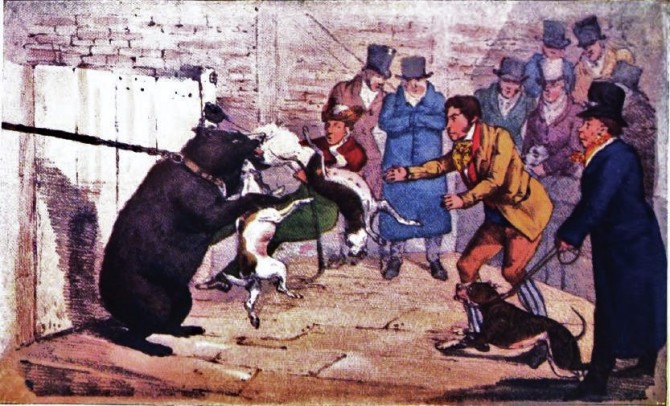

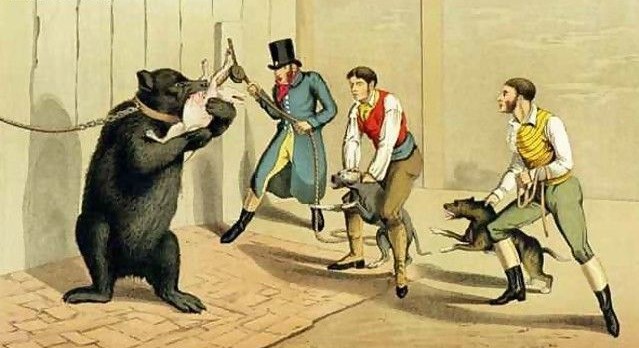

The venues for bear-baiting were called bear gardens. They consisted of a circle, fenced completely by a high wooden fence. There were raised seats around it for spectators, very like a Roman arena. A post was set in the ground at the back of the “pit.” The bear was chained to the post by his leg or his neck. A group of baiting dogs was then turned loose on the bear. In its earliest form, this dog was what we know as the Old English Bulldog. The dogs were replaced as they tired, were wounded, or were killed. The most well-known area for these events was the Paris Garden area of London, a section of Bankside lying west of The Clink at Southwark.

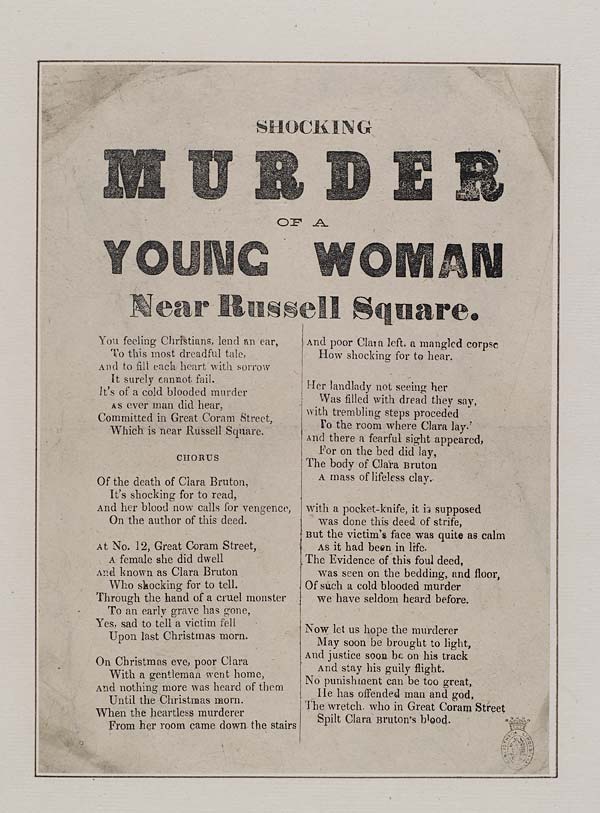

Bull-baiting was conducted in a similar fashion, with the dogs sometimes tied to the bull’s back. The last recorded bull-baiting took place in 1838. Once bull-baiting and bear-baiting became illegal, dog-fighting came into its own. It was an exceedingly popular sport amongst the aristocracy and was equally popular with the middle and lower classes, especially after the Industrial Revolution. The fact it was not legal did little to slow it down. Much as the laws today have done little to prevent it.

There were those who opposed dog fighting in all its forms. As early as the 16th and 17th centuries the Puritans opposed it – not for its inherent cruelty, but because it brought pleasure to the spectators. Those Puritans were seriously anti-pleasure. It wasn’t until the early 18th century, when people, beginning with William Wilberforce, began to read the biblical term “dominion” as “stewardship” that people began to see these sports as cruel and demeaning. Rather than seeing animals as lesser creatures to be dominated and used in any fashion man desired, Wilberforce espoused the idea that humans were put on earth to care for animals and to look out for their best interests.

Baiting sports were prohibited by Parliament with the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835. However, as I said earlier in this post, this resulted in an increased popularity in the sport of dog fighting. Legal or not, it became a lucrative business beginning in the Victorian era. Those dogs bred for bear-baiting and bull-baiting, a cross between English bulldogs and rat terriers, were called Bull Terriers. These were tough, tenacious, compact dogs of around 50 pounds with powerful jaws for tearing and biting. After 1835, larger dogs were crossed with these dogs to create the dog we know as the pitbull today.

I will not engage in the debate for or against the breed in this post. I only know my two grandnieces, ages two and three, learned to walk by pushing up on and holding on to a large white pitbull named Penny. She is their constant companion and watches over them with a vigilance many young mothers might seek to emulate.

Dog fighting was and remains one of most heinous, disgusting, and cowardly acts of cruelty ever conceived. It is the provenance of classless, ignorant, cowards – men, and sometimes women, who do not have the courage to prove their over-inflated egos by engaging in combat themselves. They prefer to force animals who have no choice to prove it for them. The only thing it proves is we have not come very far in the last 800 or so years. And we still have a long way to go. Fortunately, there are still people like, Addy, heroine of my book, Lost in Love, in the world. People who are not afraid to speak for those creatures who cannot speak for themselves. To all Athe modern-day Adelaide Formsby-Smythes in the world, I say “Thank you!” and “Keep up the fight!” To those dogs still waiting to be rescued from the wastes of human flesh who force you to act against your loving and gentle natures, please hang on. We will never give up. We’re coming for you. Hang on, babies. Just hang on.

EVERY RELATIONSHIP HAS ITS UPS AND DOWNS –

When Adelaide Formsby-Smythe insults the Duke of Selridge to the point she sees her own murder in his eyes, her wish that the ground would open up and swallow her seems a perfectly reasonable response. Until it does.

Thus, Major Marcus Winfield, now the Duke of Selridge, ends the worst year of his life by falling into an underground cave with the younger sister of his former fiancée. An offense punishable by—marriage!

EVERY MARRIAGE HAS ITS SECRETS –

Although he never imagined marrying Adelaide, Marcus decides they will limp along quite well together. There’s no need to mention he’s being blackmailed… or that his irritating new wife fills his nights with a passion he cannot deny.

Adelaide, however, having unexpectedly married the man of her dreams, will settle for nothing less than her new husband’s heart. She’ll make him love her. Far less bothersome that way when she has to tell him she’s a thief. And possibly a murderess.

AFTER ALL, EVEN THE ROAD TO FOREVER HAS A FEW BUMPS ALONG THE WAY.

Lost in Love is available now through these links :