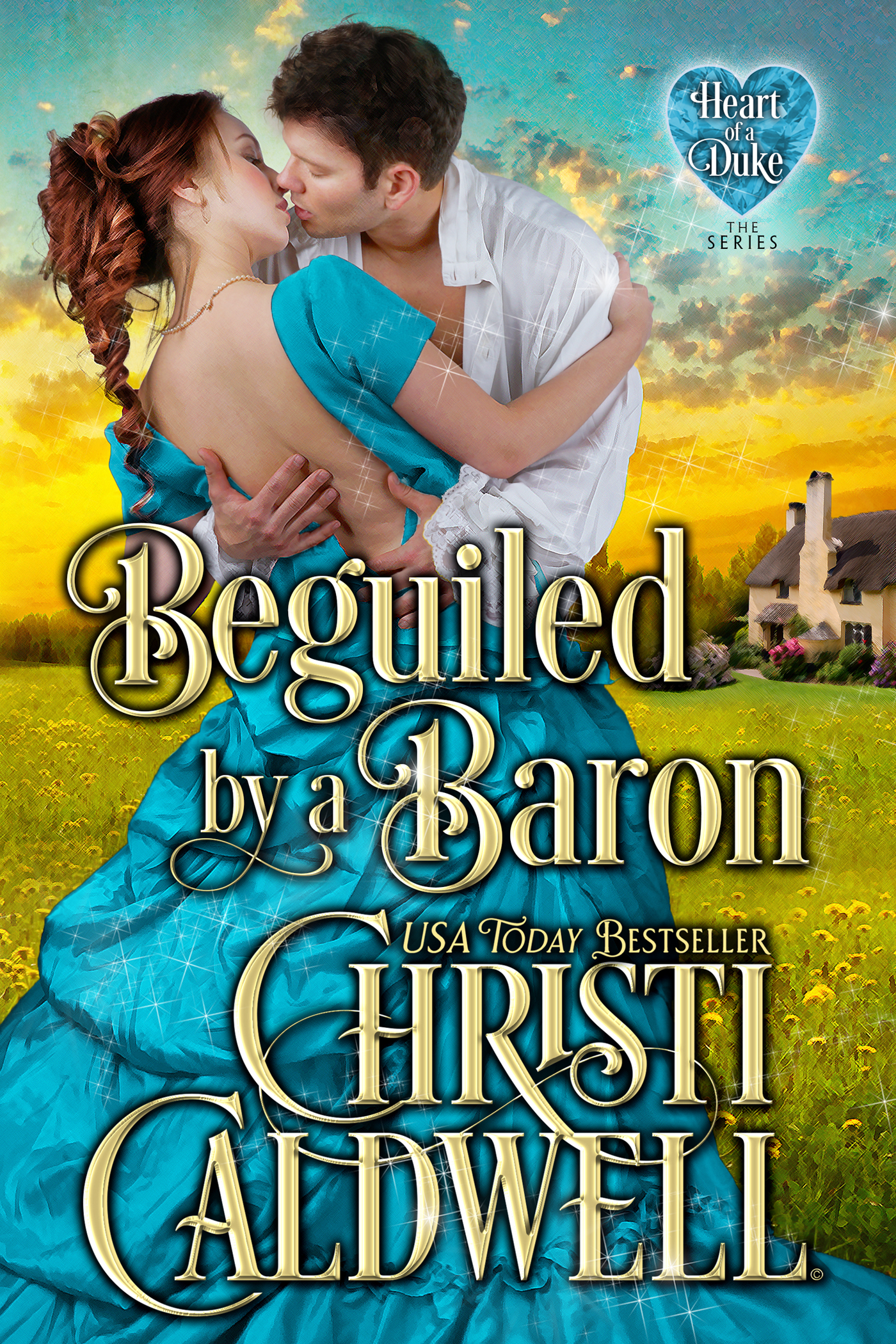

Excerpt from : Beguiled by a Baron

His brother may have failed to find an appropriate housekeeper in the last woman to hold the post, but there could be no doubting this one’s skill and knowledge. “Shall we?” Not waiting to see if she followed, he guided her from his most rare Collection Room to the one in the next hall. “In here, you’ll find all works of Western artists. From Shakespeare to his friends Herminge and Condell, you’ll find all the greatest here.”

He stole another peek at his housekeeper in time to detect the disapproving way in which she wrinkled her nose. “Only Western artists?”

Tamping down a grin, he guided her across the hallway to the adjacent room. “The finest of the Oriental literary masters is shelved in here.” Letting them inside, Vail displayed some of his finest books. “The Tale of Genji—”

“Genji Monogatari,” she whispered, touching a hand to her mouth.

“As well as Makura no Soshi,” he finished, supplying that Japanese title. He tamped down his tangible surprise at the depth of her proficiency in text. He wasn’t so snobbish that he’d be startled by a young woman’s mastery of Oriental literature, but neither was he so connected to women who had a grasp of even Western texts. His appreciation grew for the composed Mrs. Hamlet. “Shall we?”

The lady nodded eagerly. “Have you read all these titles?” she asked, as they resumed their tour.

“Many. Not most. My collections are too vast,” he said without inflection. It was a matter of fact, more than anything. “Not as impressive as Lord Dandridge’s, whose floors caved in from all the books he kept.”

A startled laugh spilled from the lady’s lips. Enchanted by the husky beauty of it, he looked over.

“You joke,” she charged, a sparkle in her eyes.

He swallowed hard. Blast if he wasn’t captivated by her wit and her bloody smile. “Indeed, not,” he forced himself to answer. Affixing a grin to his face, he leaned close to her ear. “Hardly as shocking as Lord Templeton who has a problem with rats and shoots them at all hours of the night to keep them from his texts.”

The lady widened her eyes. “Surely you jest now?”

Actually he’d didn’t. Mrs. Hamlet revealed her naiveté where his world was concerned and he far preferred her as just a woman with a deep appreciation for literature. Not wanting to disillusion her with the ugly he’d witnessed, Vail winked, earning another laugh. The sound of it did funny things to his heart’s rhythm. Unnerved, he hurried through the remainder of the tour, showing his housekeeper the seven rooms where his titles were kept. After they’d finished, the lady fell silent.

“Well?” he urged as they arrived at his office.

She gave her head a wistful shake. “It is a shame someone else will have possession of all these great works.”

And just like that, she’d brought them ’round back to her earlier disapproval. Not knowing why that should matter, just that it did, Vail rang the bell, needing for a restoration of his own logic where Mrs. Hamlet was concerned. “Mr. Lodge will show you to your rooms. You may have the day to familiarize yourself with the residence and have Mr. Lodge perform your introductions to the staff.”

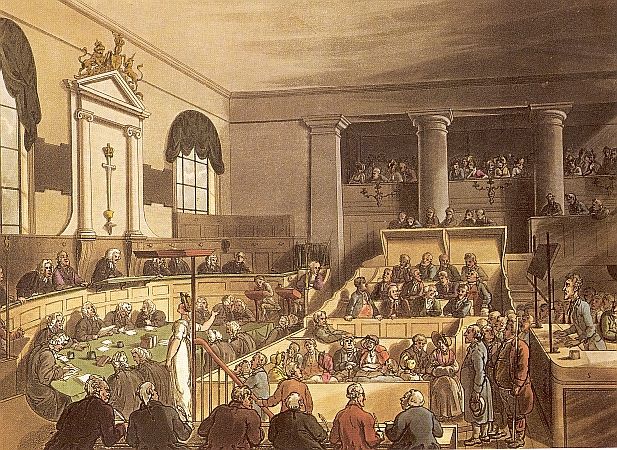

This delightful excerpt from Christi Caldwell’s wonderful new historical romance hints at the hero’s knowledge of the Regency phenomenon – bibliomania. The author does an amazing job of setting a passionate love story in the middle of the world of the antique book dealer and the lengths to which Regency gentlemen went in order to acquire new volumes for their collections.

To read more about bibliomania, check out our previous post here :

And to read a poignant, witty, and moving love story set in the world of books and mania, check out Beguiled by a Baron, out today !!

A Lady with a Secret… Partially deaf, with a birthmark marring her face, Bridget Hamilton is content with her life, even if she’s been cast out of her family. But her peaceful existence—expanding her mind with her study of rare books—is threatened with an ultimatum from her evil brother—steal a valuable book or give up her son. Bridget has no choice; her son is her world.

A Lord with a Purpose… Vail Basingstoke, Baron Chilton is known throughout London as the Bastard Baron. After battling at Waterloo, he establishes himself as the foremost dealer in rare books and builds a fortune, determined to never be like the self-serving duke who sired him. He devotes his life to growing his fortune to care for his illegitimate siblings, also fathered by the duke. The chance to sell a highly coveted book for a financial windfall is his only thought.

Two Paths Collide… When Bridget masquerades as the baron’s newest housekeeper, he’s hopelessly intrigued by her quick wit and her skill with antique tomes. Wary from having his heart broken in the past, it should be easy enough to keep Bridget at arm’s length, yet desire for her dogs his steps. As they spend time in each other’s company, understanding for life grows as does love, but when Bridget’s integrity is called into question, Vail’s world is shattered—as is his heart again. Now Bridget and Vail will have to overcome the horrendous secrets and lies between them to grasp a love—and life—together.

Amazon: http://amzn.to/2rmLp6l

iBooks: http://apple.co/2rvOEXZ

Kobo: http://bit.ly/2qSnoRr

Barnes and Noble: http://bit.ly/2rBMuHL

USA TODAY Bestselling author CHRISTI CALDWELL blames Julie Garwood and Judith McNaught for luring her into the world of historical romance. While sitting in her graduate school apartment at the University of Connecticut, Christi decided to set aside her notes and pick up her laptop to try her hand at romance. She believes the most perfect heroes and heroines have imperfections, and she rather enjoys torturing them before crafting them a well deserved happily ever after!

Christi makes her home in southern Connecticut where she spends her time writing her own enchanting historical romances, chasing around her feisty seven-year-old son and caring for her twin princesses in training!