BY LOUISA CORNELL

I know of few horse-mad little girls who have not read Marguerite Henry’s King of the Wind, which won the Newbery Medal as the “most distinguished contribution to American literature for children” in 1948. I still have my much-loved hardbound copy. I daresay not many of those little girls realized Henry’s book was a fictionalized biography of perhaps the greatest foundation sire in the history of Thoroughbred racing. King of the Wind took a great deal of its material from the legends and folklore which surrounded the stallion, sometimes known as Sham or Shamim. The real story of his arrival in England is in all likelihood a little less dramatic.

So far as we know, the horse who would become the Godolphin Arabian was foaled in 1724 in Yemen. As a young colt he was sent by way of Syria to the stud of the Bey of Tunis. It is believed the colt, along with a few others, was sent as tribute to Louis XV in 1728. Due to the long sea voyage the horses did not appear at their best, and the king was not impressed. In spite of that, it is doubtful Sham was used as a cook’s carthorse, no matter what the legends might say.

We do know the horse was imported from France to England in 1729 by Edward Coke, a gentleman with connections at court, including the Duke of Lorraine (later Francis I of Germany.) It is thought Coke acquired Sham by way of the French court, perhaps from the Duke of Lorraine himself. Coke stood the young stallion at stud at his newly purchased Longford Hall in Derbyshire.

One of Sham’s first offspring was out of Coke’s mare, Roxanna. This colt, Lath, foaled in 1731 was said to be a beautiful and elegant horse. He was sold to the Duke of Devonshire. Lath was considered the fastest racehorse of his day, faster than Flying Childers had been. He won the Queen’s Plate nine times out of nine at Newmarket. He was not as successful at stud, but his daughters went on to become important dams in the history of British racing. If you have read the other posts in this series you will know the duke had a taste for well-bred horses. In spite of his many flaws, you have to admire a man for that. Or perhaps only those of us who love Thoroughbreds do.

Unfortunately, Edward Coke died a young man, only 32 years of age, in 1733. He left his mares and foals to his friend, Francis, the 2nd Earl of Godolphin. He left his stallions – Sham, Whitefoot, and Hobgoblin – to one Roger Williams. However, in 1733 the Earl of Godolphin bought Sham from Mr. Williams and thus the horse became known as the Godolphin Arabian.

Descriptions of the Godolphin vary. The first recorded was that of the Vicomte de Manty who upon seeing Sham on the colt’s arrival in France described him as “beautifully-made although half starved, with a headstrong temperament that made him unloved among the barn staff.” He was an Arabian. What did they expect?

William Osmer, veterinarian and one of the men who knew the Godolphin best said:

“Whoever has seen him must remember that his shoulders were deeper and lay farther into his back than any horse yet seen; behind his shoulders there was but a small space; before the muscles of his loin rose excessively high, broad, and expanded, which were inserted into his quarters with greater strength and power than any horse ever yet seen of his dimensions. It is not to be wondered at that the excellence of this horse’s shape was not in early times manifest to some men, considering the plainness of his head and ears, the position of his fore-legs, and his stunted growth, occasioned by want of food in the country where he was bred.”

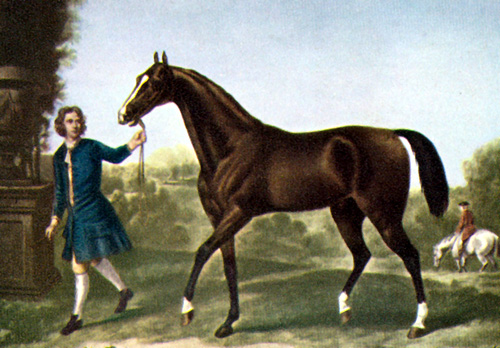

The reference to his stunted growth referred to his relatively short stature. Reports have him standing somewhere between 14’2 and 15 hands high. There is an early portrait of him in Lord Cholmondeley’s collection at Houghton. It is said to be a glamorized image, whilst Stubbs’s portrait is said to be an accurate depiction of a horse thought not particularly handsome by the standards of the day.

by George Stubbs

The Godolphin Arabian was Britain’s Champion Sire in 1738, 1745, and 1747. His most well-known colts were Lath, Blank, Cade, and Regulus – all outstanding racers. The latter three became champion sires in their own right. He also sired two important fillies – Matchless and Selima, who went on to become the dams of some of racing’s most important lines. The major Thoroughbred sire, Eclipse, traces his sire’s line back to the Darley Arabian, but his dam was a daughter of Regulus, thus Eclipse’s line is traced back to both of these founding sires of British racing.

Today the majority of thoroughbreds trace their sire line back to the Darley Arabian. However, many of America’s finest racers trace their sire line back to the Godolphin Arabian. These include Seabiscuit, Man o’ War, War Admiral, and Silky Sullivan. And a great many of the horses who trace their sire line back to the Darley Arabian can trace their dam’s line back to the Godolphin Arabian.

Both the Darley Arabian and the Godolphin Arabian’s descendants have inherited skeletal and cardio anomalies which gift them with the build and stamina for racing. Passed along the sire lines, they have a shorter back, with five lumbar verterbrae rather than six, which gives them a longer stride. Secretariat’s stride was twenty-five feet, second only to that of Man o’ War, which was twenty-eight feet. And from the dam lines, they have abnormally large hearts, responsible for their incredible stamina. Secretariat’s heart weighed 22 pounds, twice the size of an average horse’s heart. I find it particularly fitting they inherit their hearts from their mothers.

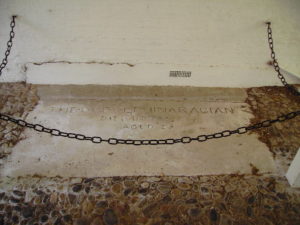

The Godolphin Arabian stood at stud for over twenty years, the cat Grimalkin his one constant companion. He died on Christmas Day in 1753. His age was estimated to be 29 years. He was buried in the stableblock at Wandlebury House at Gog Magog in Cambridgeshire with solemn ceremony and a tribute of cake and ale drunk by the mourners. The house was torn down in 1956, but the stableblock remains and can be visited today, as can the grave.

Godolphin Arabian

Marguerite Henry’s book was a fictionalized account of this incredible horse’s journey to legend. However, there are two quotes from her work I hold to be true for the Godolphin Arabian and his fellow founding fathers. Three horses far from home who came to England and wrote their names in the history of British racing forever.

When Allah created the horse, he said to the wind, ‘I will that a creature proceed from thee. Condense thyself!’ And the wind condensed itself, and the result was the horse.

But some animals, like some men, leave a trail of glory behind them. They give their spirit to the place where they have lived, and remain forever a part of the rocks and streams and the wind and sky.

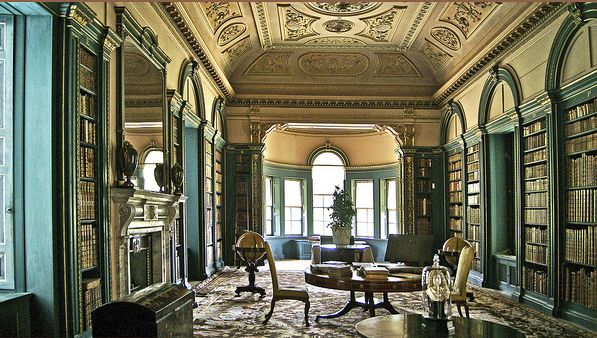

The library at Blickling Hall. Look at all of that natural light.

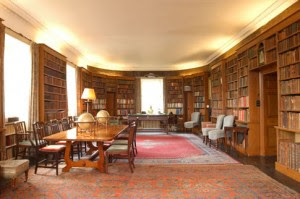

The library at Blickling Hall. Look at all of that natural light. Ramerscale House Library.

Ramerscale House Library.

It needs a comfy chair, but that ceiling!

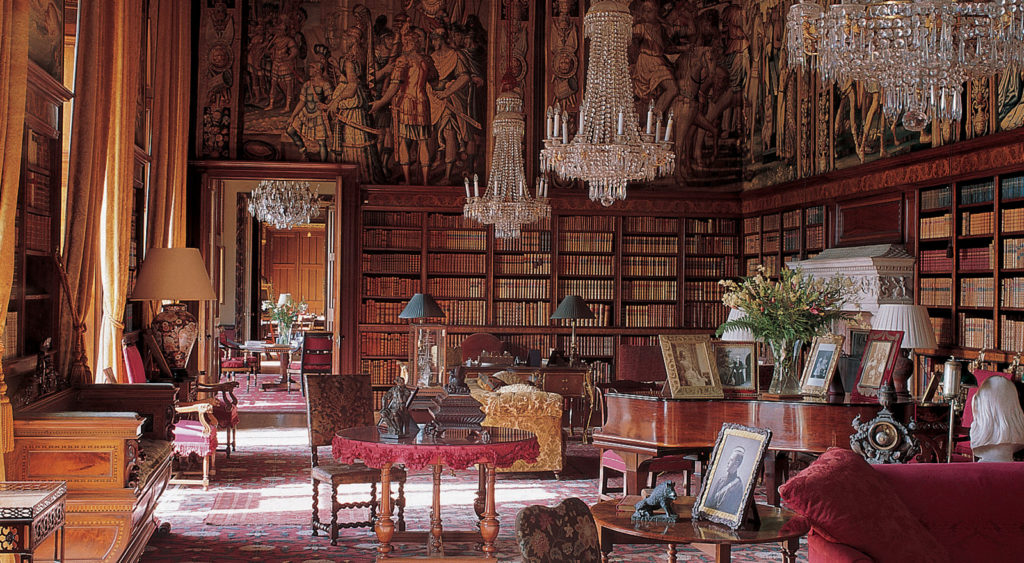

It needs a comfy chair, but that ceiling! And the Nirvana of stately home libraries – Chatsworth – within whose walls over 20,000 books reside. Sigh!

And the Nirvana of stately home libraries – Chatsworth – within whose walls over 20,000 books reside. Sigh!