by Louisa Cornell

Having covered the all-important drawing room and the equally vital kitchen areas of your average Regency era English country house, I thought it imperative we visit… The Necessary. Anyone who has read their British history knows this era was on the cusp of modernity in many areas. Plumbing was one of them. Sort of. For those who write and even those who read Regency era romance I offer a brief primer on where your hero or heroine might go… to Go.

The Water Closet or WC – Nicest of our options.

By way of introduction, there was actually a flushing toilet in Britain as early as 1591. John Harington, godson of Queen Elizabeth I, invented and installed the first water closet in his own home. He called his new invention Ajax and even wrote a book describing how it was built and how it functioned. A pan had an opening at its bottom closed by a leather faced valve. A system of handles, levers and weight poured the water from the cistern and opened the valve.

It didn’t really catch on, but by 1775 Alexander Cummings took a patent for his flushing closet which was very similar to Ajax. The main drawback in Ajax was the water seepage through the primitive valve. In 1777, Samuel Prosser used a ball valve to stop the seepage of water from the tank. This was the prototype for the water closets seen in some Regency era stately homes and London townhouses.

Some of the problems with this facility were –

- There tended to be only one in each house. Large house, one water closet, cold dark nights. Take a good candle, warm slippers, and do not wait until the last minute!

- Only in the wealthiest and most modern-thinking houses would the water closet be found on the floor with the family bedchambers. So, marry really well or… See Number 1 above.

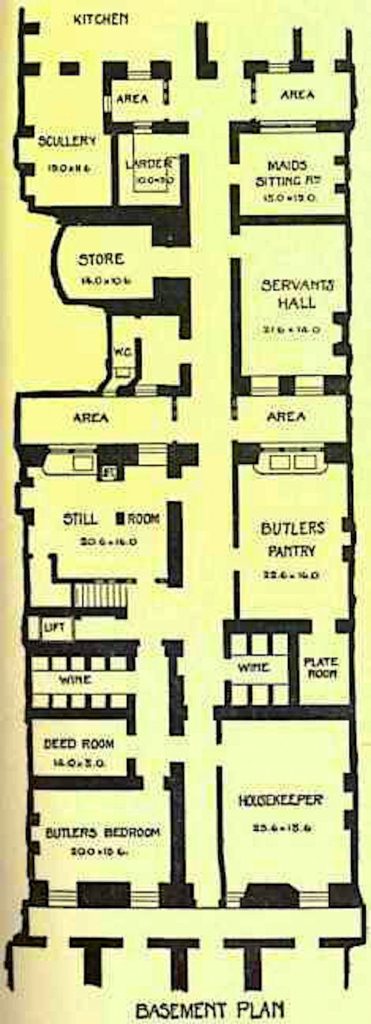

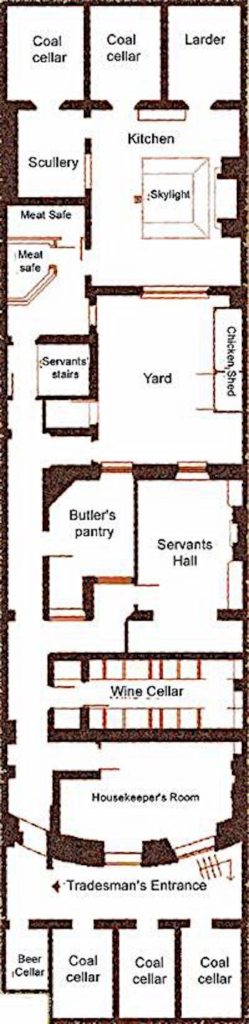

- The most logical location for the water closet would be on the ground floor at the back of the house where water was already being pumped inside aka the kitchens. Which means one ran the risk of running into or even tripping over sleeping servants on your way to the water closet.

- Negotiating a wooden toilet seat, in the dark, in homes where rat catchers were employed to keep the vermin population in check. Do not skimp on paying either the rat catcher or the estate carpenter. Just saying.

The advantages were –

- One didn’t have to leave the house.

- The maid didn’t have to empty it every time it was used.

- Some of them worked well enough to completely eliminate the smell and possibility of disease from the house.

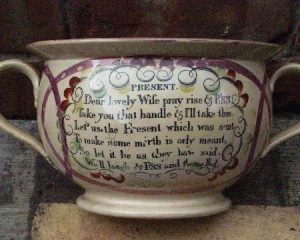

The Chamber Pot – Great for your Heroine, Not so great for her maid!

A chamber pot was a bowl or container and could be as fancy or as basic as the owner deemed necessary. Some resembled black iron cook pots with a lid. Others were beautifully decorated porcelain vessels, often matching the decor of the bedchamber or the pitcher and bowl on the bedchamber washstand. It is safe to say a chamber pot might be found in every bedchamber in every stately home and town house in England during the Regency era. I daresay even servants had chamber pots in their bedchambers. Why wouldn’t they? They certainly had enough experience emptying them.

As the name denotes, a chamber pot might be found in any sort of chamber. The French were horrified to discover that British men kept a chamber pot in the dining room so as not to interrupt their after dinner brandy and cigars with a trip to the privy or water closet. Yes, you heard me correctly. A chamber pot. In the dining room. It might be stored behind a screen or even in a cabinet of the sideboard. And apparently gentlemen had no compunction about pulling the chamber pot out and using it whilst their fellow gentlemen watched. Frat boys have been around considerably longer than we knew.

For the ladies, during most social events a withdrawing room was designated. This was not a permanent fixture in a home, although some particularly busy homes might make it so. Perhaps a small parlor or a room not in constant use by the family would be set up with a screen and a chamber pot, chairs or comfortable divans for ladies to rest away from the party, a wash stand equipped with a pitcher of water and a bowl in which to wash one’s hands and face, along with towels and face cloths. A full length mirror and the talents of a maid who could repair a torn hem or flounce might also be offered. A vanity with cosmetics and a maid who excelled at dressing hair might be included. Of course there would be a maid whose job it was to empty the chamber pot and clean it so the next lady might use it. As far as all extant sources state, using the chamber pot was not a spectator sport for the ladies. Of course, ladies had the advantage of not having to remove any clothing in order to use the chamber pot. During the Regency era ladies did not wear the sort of confining panties or drawers we do today. Only loose women wore drawers, which means French women did it first. Wicked girls!

When in the actual bedchamber, chamber pots might be kept under the bed, behind a screen or even hidden in a sort of cabinet. They might be installed in a sort of toilet chair in a dressing room as well. No matter where they were stored, it was the duty of a maid to empty said chamber pot and return it clean to be used again.

Ladies were even afforded a more portable option for when they traveled to venues at which a withdrawing room might not be made available – the bourdaloue.

For an informative and fun article on the bourdaloue please check out this link.

There were advantages and disadvantages to the use of a chamber pot.

Advantages –

- One did not have to leave the room, let alone the house at night to use it.

- One might use it without alerting the entire house, let alone a ballroom full of guests one was using it.

- A maid emptied it outside of the house, thus ridding the house of any smell or possibility of disease.

Disadvantages –

1. It might be in one’s chamber a while before it was emptied.

2. Maneuvering to use it might be problematic.

3. If one was a maid or footman working in one of these homes… do I really need to explain that disadvantage?

The Privy – You Might Be a Regency Redneck If… Oh! Wrong Post!

By the early 19th century, before the advent of sewer systems, each London house and most country houses would have what was called a ‘cesspool,’ a pit about four feet wide and six feet deep, above which the home’s privy was located. Liquid waste would be absorbed back into the soil at the bottom of the hole, but solid waste had to removed by the night soil man, who would come around at night (opening a cesspool during the day was illegal, as the smell was considered to be too horrifying) and climb down into the cesspool to shovel out the accumulated muck. Rest assured these cesspools probably accumulated their fair share of other household rubbish as well. More than one murder was discovered when someone bent to the task of removing solid waste from the cesspool. Shudder.

The privy was a fixed out house with no water supply or drain and usually located some distance away from the house. A fixed wooden seat with a rounded hole was placed directly over the cesspit. Occasionally privies were attached to the side of a building, projecting out from a top floor, or reached through on outdoor entry on the ground floor of a service wing. These were sometimes called garderobes, a leftover term from the medieval period. More often than not they were placed at some distance from the main house at the far end of a garden or yard.

The advantages to this arrangement were… let me think. Surely there was…

- The privy was away from the house.

- More often than not the owners paid for the services of the night soil man, thus the servants did not have to empty it. At least in the city. In the country, it is a safe bet there was some poor servant assigned to this task.

The disadvantages were –

- It was away from the house. Long walk, no matter the weather or the time of night. Much more likely to encounter the sort of animals who prefer to occupy a privy.

- Do we really need to list all of the disadvantages of using a privy?

There you have it. The name of the room we call a bathroom or restroom, or at least the various places and things one might use to accomplish the same purpose. Everyone who is perfectly happy to read or write about the Regency era, but has some reservations about actually living during the era, please raise your hand. You’re excused.

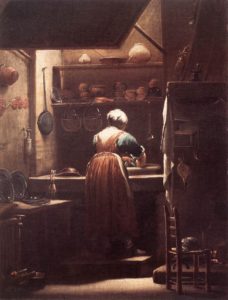

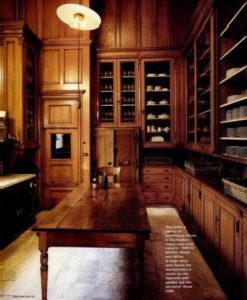

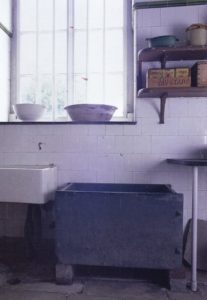

No this is not my kitchen. Too few books on the counters and not enough dirty dishes. And there’s no dog trying to get into the fridge.

No this is not my kitchen. Too few books on the counters and not enough dirty dishes. And there’s no dog trying to get into the fridge.