Louisa Cornell

One of the major industries in the north of England during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was mining. From Yorkshire, through Cornwall, and throughout Wales it was a way of life and a way of living for many of those areas’ poorest citizens. Whilst most mines were owned and run by private industrialists, some were part of the financial support of the great estates of the aristocracy. It was an industry that employed men, women, and children with very little discrimination between their duties. Mines producing coal, tin, and arsenic were the most profitable. They were also the most dangerous.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the use of steam engines for hoisting and water pumping enabled the deepening of coal mines in England. Because seams were being dug at deeper levels, explosions in coal mines increased. At deeper levels fire-damp, what we know as methane today, was more prevalent. As a result, in the early nineteenth century many pitmen died in northern England due to large mining explosions. In fact, between 1786 and 1815, major explosions accounted for 558 deaths in Northumberland and Durham alone.

Explosions occurred when fire-damp, released by miners tapping into a gas pocket in the mine, met with the point of the flames of tallow candles used by miners to illuminate their work areas. These meetings of fuel to flame initially resulted in a violent out-rush of gas from the ignition source. However, almost immediately after that an in-rush, called an after-blast by miners, filled the vacuum left by cooling gases and steam condensation.

A catastrophic mine explosion not only killed with the violence of the blast and fire, but it also wrecked the brattices in the mines, destroyed corves, tubs, rolleys, ponies, and horses. The resulting debris made it nearly impossible for miners to escape or for rescuers to reach them. The destruction of the ventilation systems led to the asphyxiation of miners by lethal after-damp resulting from the combustion. After-damp was a lethal gas formed in mines after oxygen was removed from an enclosed atmosphere. It consisted of argon, water vapor, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide.

On 25 May, 1812, the mining operation at Felling suffered one of the worst major pit disasters in England. In the end, it claimed ninety-two lives. It was the first major explosion to provide reasonably accurate records of the incident. Situated between Gateshead and Jarrow in Country Durham, the explosion at Felling was heard up to four miles away. A cloud of coal dust fell over the neighboring village of Heworth like black snow. It took nearly seven weeks to remove the dead after putting out the fires and waiting for the after-damp to disperse. Ninety-two men and boys lost their lives and their funeral procession was made up of ninety coffins when it finally reached the church.

After the Felling mining disaster there was a public outcry for mine safety. The Reverend John Hodgeson (1799-1845), who comforted the bereaved and buried the dead, began a correspondence with Sir Humphry Davy (1778-1829,) a prominent man of science.

Sir Humphry Davy was the director of the laboratory at the Royal Institution of Science from 1801-1825. He was the professor of chemistry there from 1802-1812. He was an honorary professor from 1813-1823. He discovered the physiological effects of nitrous oxide (laughing gas.) He used the newly devised electric battery to isolate sodium and potassium. He did a great deal to establish the Royal Institution’s reputation for excellent lectures and important scientific research.

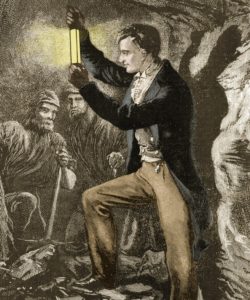

As a result of the efforts of Reverend Hodgeson, Sir Humphry traveled to Durham to conduct an investigation of fire-damp. He was provided with samples of fire-damp in sealed wine bottles from the mines at Hebburn. A number of other men began to study the phenomenon as well. Most prominently George Stephenson, about whom I will write in another blog post.

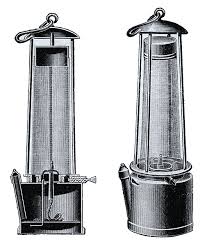

After a great deal of investigation, Davy discovered a flame could not ignite fire-damp if said flame was encased in a cage of wire mesh. He showed a mesh of twenty-eight openings to the inch, if configured into two concentric mesh tubes, cooled combustion products so that the flame heat was too low to ignite the gases outside the mesh. His final prototype was a wick lamp encased in the double mesh cage. The lamp also provided a test for the presence of gases. The flame of the Davy lamp burned higher and with a blue tinge if flammable gas was present. If the mine was oxygen-poor the flame would be extinguished completely. This gave miners the chance to escape the mines before they were asphyxiated.

The first trial use of his lamp was carried out at at Hebburn Colliery on 9 January, 1816. The trial was a great success and the Davy lamp immediately went into production. Did it stop explosions in mines in England? No. With the advent of the Davy lamp, many mining companies only strove to dig deeper mines exposing miners to other dangers. Many miners still insisted on taking candles into the mines to light their way. Some miners were suspicious of the lamps, as happened all too frequently in this era when it came to science.

However, the advent of the Davy lamp and other versions of mining safety lamps did eventually create a safer work environment for those working in England’s mines. It was the beginning of efforts by the British government, the mining industry, and men of science to make mining a more survivable employment. It opened the way for more mining improvements and oversight that continued well into the twentieth century.

I discovered a great many fascinating things about the early mining industry in England whilst researching for my latest historical romance Thief of Broken Hearts. The heroine, Rhiannon Harvey de Waryn, Duchess of Pendeen, has run the family seat of the de Waryn family since she was a young girl and part of the estate’s fortune is in the tin and arsenic mines. She introduces the Davy lamp into the mine operations against the wishes of many of the miners there.

Excerpt from : Thief of Broken Hearts

Endymion, having shed all curiosity as to how these people knew who he was, raced in the direction the woman had pointed until he came upon a wide chamber, shored up by thick timbers at regular intervals. He came to a precipitous stop. In the middle of the chamber, dressed in a dull brown kerseymere dress and pelisse, stood his wife, covered in dust and perfectly at ease.

I’m going to kill her…right after I turn her over my knee.

A bandy-legged miner, hat in hand, argued with the duchess whilst an older man with a greying beard and dressed like a gentleman farmer looked on, some sort of lamp in his hand. “I don’t like it, Yer Grace. It ain’t natural. Not a thing wrong with the lamp I had,” the miner said, eyeing the lamp in the older man’s hands as if it were a snake poised to bite.

“I’ll tell you what isn’t natural, George Watts.” Rhiannon pushed a strand of hair off her face. “Blowing yourself and half your mates to kingdom come because you are too stubborn to try something new.” She snatched the lamp from the bearded man and shoved it into the miner’s chest. “Either you use the Davy’s lamp or you can join your wife and mother-in-law at the calciners.”

Torn between admiration and anger, Endymion stepped to his wife’s side and, before she noticed his presence, dragged her arm through his. “Do as she says, George. You’ll keep your wits longer. If this is settled, I’d like a word with you, madam.”

Her eyes wide and her color high, Rhiannon tried to free her arm. “What are you doing here? I don’t have time to entertain you, Your Grace. I have work to do.”