Victoria here, reporting on a delightful presentation I attended in Naples, FL, at the public library. Presenter Cheryl Lampard, who is a consultant on fashion, make-up and image, spoke on royal style to an eager group of mostly females who peppered her with questions at the end of her talk — mostly about the upcoming royal wedding. What did she think the Queen would wear? What about the royal limousine, THE dress and so forth. I can reliably report that here in FL, the audience for the great event will be huge.

Cheryl Lampard’s business is Style Matters International, based in Naples. Click here for her website.

Ms. Lampard’s power point talk began with a discussion of “Dress for Success” Elizabethan style. Ms. Lampard says, “Your image is your brand” and that applies to royalty as well as to the rest of us. Elizabeth I needed to project an image of power nobles to foreign diplomats to the great mass of her subjects. The luxury and splendor of her clothing represented the powers and strength of the nation over which she ruled.

Elizabeth I inherited her father’s fine taste and flair for showmanship. The first Elizabethan Era is celebrated for its achievements, particularly in the arts, e.g. Shakespeare. At left, Elizabeth I (1533-1603) as a girl, whose future was anything but assured. Nevertheless she outlasted her half-brother, Edward, and her half-sister Mary, to take the throne in 1558 at age 25. She ruled for 44 years, overcoming both internal threats (e.g. Protestants vs. Catholics) and external threats from continental powers.

At left, Elizabeth I (1533-1603) as a girl, whose future was anything but assured. Nevertheless she outlasted her half-brother, Edward, and her half-sister Mary, to take the throne in 1558 at age 25. She ruled for 44 years, overcoming both internal threats (e.g. Protestants vs. Catholics) and external threats from continental powers.

In the painting, Tudor style prevailed in dress, jewelry, hair and make-up. As Ms. Lampard pointed out, nothing is new when it comes to fashion; we see cycles of clothing and make-up styles throughout history. A primary example: the wasp waist. Clothing emphasized the narrowness of the waist in contrast to the wide skirts and sleeves. As time went on, Elizabeth I’s fashions exaggerated the small waist, as well as sumptuousness in fabric and decoration.

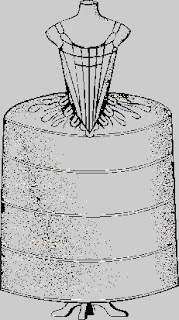

To emphasize the narrowness of the wasp waist, women wore a “stomacher,” in the shape of a triangle across the chest and pointing down at the waist. Often richly decorated, the stomacher was a separate piece of clothing that was tied or otherwise fastened on and used with a variety of gowns.

A set of hoops called a farthingale spread out the skirt and widened the gown from hips to floor. Both the stomacher and farthingale were stiffened with wood, whalebone, ivory or mother-of-pearl.

The effect was obviously to make the waist look small in comparison to the hips, carrying the hourglass figure to extremes. Full sleeves and wide shoulders add to the illusion.

The Armada Portrait (at Woburn Abbey with other versions and/or copies elsewhere) shows Elizabeth I in a setting rich with important and impressive symbolism. The gown of expensive satins and silks is crusted with jewels, emphasizing the prosperity and magnificence of the court. Her hand rests on the globe, to portray England’s dominance of the sea, and on either side of her head, two stages of the 1588 defeat of the Spanish Armada can be seen.

By late in Elizabeth I’s reign, everything was exaggerated. The skirts were amazingly wide and heavy. The sleeves look like her arms would be nearly unmovable. The tall r

uffs would make turning her head uncomfortable.

The make-up, too, was dangerous. Pale skin was admired, signifying that the person never had to work in the outdoors. In another recurring fashion trend, this white make-up was lead- based well into the 19th century, poisonous to the system and causing pockmarks on the face. Fashion can be foolish indeed.

Ms. Lampard described many more details about Elizabethan fashions, the sleeves, the ruffs, (tall, starched, and probably scratchy), and the discomfort endured for the sake of image. She jokingly compared these fashions with today’s exaggerated platform stiletto-heeled shoes.

Moving to the Victorian period, she discussed the return of the wasp waist, the continued need for the monarch to project an image of stability and power, and the adoption (forever and ever) of Victoria’s white wedding gown as the standard for brides worldwide. Formerly, she said, silver had been the usual color for royal brides.

Victoria became the mother of nine children, then endured a long period of mourning after her husband’s death. But she knew how to dress for the role of head of the empire.

Even in the 1880’s Victoria kept up appearances. Below, a photograph of Queen Victoria

for her Diamond Jubilee in 1897.

Moving on to today’s era, the second Elizabethan Age, we see again in the young Princess Elizabeth, the recurrence of the wasp waist, for her 1947 wedding gown and a few years later for her coronation in 1953.

|

| Wedding gown, 1947, by Norman Hartnell |

|

| Coronation gown, 1953, by Norman Hartnell |

Although the current Queen Elizabeth has not been in the forefront of fashion trends, she too has recognized her obligation to represent her nation in a modern way. For ceremonial events, of course, she is suitably gowned, crowned and bejeweled. For her day-to-day activities, Ms. Lampard said, she can be particularly admired for her choice of hats. Designing a hat that is flattering, attractive and capable of having the monarch’s face visible is not an easy job.

Here are a few views of the Queen’s headgear.

All in all we had a wonderful time last week covering centuries of royal fashion and chatting about the wedding to come. Many thanks, Cheryl Lampard of Style Matters International.

You always attend the most wonderful events! I would LOVE to see a presentation like this! Thank you for sharing it with us!