BUT NOT IF THEY WERE WELSH!

Accusations of witchcraft across Europe for several centuries resulted in the persecutions, imprisonments, torture and executions of hundreds to thousands of people, most of them women. There were an estimated 1000 executions in England, and between 3,000 and 4,000 killings in Scotland. However, oddly enough, only five people were hanged for witchcraft in Wales. Why?

After all, Welsh court records dating from the 16th century, held at the National Library of Wales, show that suspicions and verbal accusations of witchcraft like those seen across the rest of Britain and Europe were common in Wales. They also happened under similar circumstances where accusations often followed an argument, or a request for charity which was denied.

The records indicate bitter arguments between neighbors and family members often precipitated these accusations. Horses were killed, cattle were bewitched, pigs perished, men and women were injured, there were miscarriages and even murders in these accusations. Their accusers were neighbors, relatives, and in many cases, people with financial and personal reasons to make such accusations. However, if a case came to court, juries usually found the accused not guilty. Again, we ask Why?

Actually, there were a couple of very good reasons.

First of all, Wales was considered a land of magic, enchantment, superstition, and connection to the supernatural long after the rest of Britain had become enlightened. People from the rest of England, both the wealthy and aristocratic and the poor and uneducated, often went to Wales looking for consultations with enchanters and soothsayers and healers.

Wise women, cunning folk and soothsayers, were highly regarded in Wales, using magic to perform important services for the community. They were often the only physicians available in entire counties. Their knowledge of herbal medicine and folk remedies was unsurpassed in Britain. They served as midwives, arbitrated arguments, advised on animal husbandry and crop plantings, and performed myriad other services through the simple witchcraft of centuries of knowledge passed down from mother to daughter.

Women in Wales even looked like witches. They tended to dress in long, heavy woolen skirts, aprons, blouses and large woolen shawls. Most village women brewed mead and ale. They let their community know that there was ale for sale by placing some form of signage outside their cottages. The most popular and well-remembered of these signs was a broomstick.

There is speculation among some researchers that the traditional tall, black hat of the Welsh woman served as inspiration for the wide-brimmed hat of the fairy tale witch.

Another good reason was the adherence of the Welsh to unreformed religion long after the Church of England was established and made the faith of Britain. The Welsh preferred to worship within the household in ways that mimicked Catholic practices. They believed in prayer rather than doctrine. There is evidence that many people continued to seek the aid of charmers instead of the church. Elizabethan and Stuart politicians frequently spoke about the religious ignorance in Wales.

Priests were asked to create curses in the form of prayers. People consulted wise women to offer prayers that melded the Catholic faith with old Celtic practices. Many in Britain considered Wales a country steeped in darkness due to their adherence to so many of the old ways.

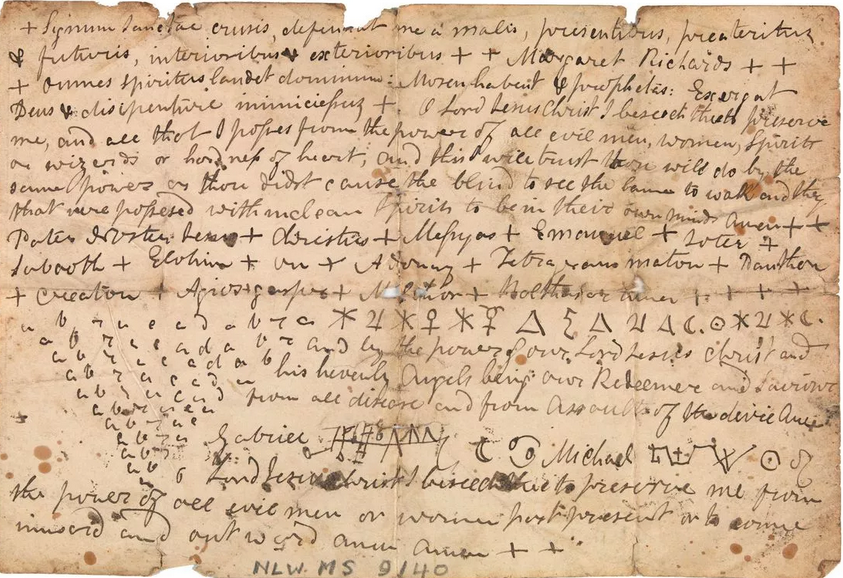

A charm attributed to Gwen ferch Ellis, the first woman to be hanged for witchcraft in Wales, included the words “Enw’r Tad, y Mab, a’r Ysbryd Duw glân a’r tair Mair” (translated as “the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit of God, and the three Marys”.) These charms were never really meant to cause harm, but only to ward off evil.

(Image: Michael Jones/National Library of Wales)

A third, and most fascinating reason was the power of language, the Welsh language, to be more specific. When witch hunts came to Wales in the form of witch hunters appointed by Parliament like Matthew Hopkins (c. 1620 – 12 August 1647) they had a number of strikes against them. In addition to the attitudes of the people who were judges and made up juries when it came to witchcraft none of the witch hunters spoke or read Welsh.

Evidence in many of these cases consisted of people hearing supposed spells and being able to speak them back to the witch hunter to be written down. Any writings of the accused witch be they recipes or books of herbal medicine were seized, but they proved useless because none of the English or Scot witch hunters could read them. Needless to say any Welsh-speaking individuals asked to translate pleaded ignorance of what was written. No sense in taking chances when it came to crossing a Welsh woman, just in case!

IN MEMORY OF THE THOUSANDS OF PEOPLE, MOSTLY WOMEN, MURDERED FOR THE SUPPOSED CRIME OF WITCHCRAFT ALL OVER THE WORLD TO THIS DAY.

AND IN HONOR OF THESE FIVE MARTYRS TO WELSH TRADITION

BENDIGEDIG FYDDO

1594

Gwen ferch Ellis, of Bettws, Denbighshire

1622

Rhydderch ap Evan, a yeoman, Caernarvonshire,

Lowri ferch Evan, Caernarvonshire

Widow Agnes ferch Evan, Caernarvonshire

1655

Margaret ferch Richard, Anglesey