Louisa Cornell

These days anyone in any sort of business knows the advantage and efficiency an attractive and well-worded business card can provide. These small embossed pieces of card stock are a relatively inexpensive and quick way to get the word out about the services one offers. Tucked away in a potential customer’s wallet or kitchen drawer they offer a chance of repeat customers or of custom from someone who discovers themselves in need of a particular service.

Brilliant idea, right? But where did the idea come from? We will likely never know precisely, but here are some things about early business cards in England, or rather trade cards, as they were more frequently called, that we do know. Their history is quite fascinating and presents a microcosm of the development of business and trade in the British Isles.

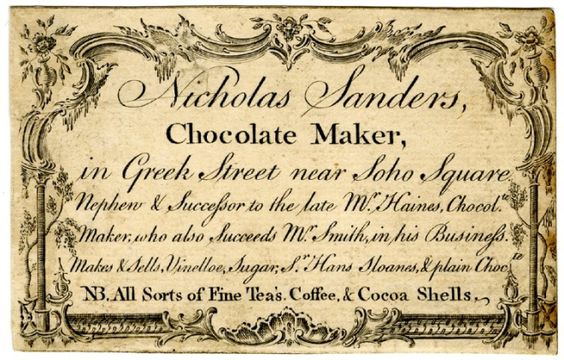

Trade cards first came into current use after 1700. There are a few examples from as early as 1630, but their consistent use is not documented until after 1700. They were originally sheets of paper ranging up to folio size. They were called by a variety of names – tradesmen’s cards, tradesmen’s bills or shopkeepers’ bills. By the nineteenth century, with the advent of so many printing techniques they ranged from calling card size to highly colored handbills known as counter cards.

The cards of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries featured some aesthetic qualities to rival and even surpass those of today. They reflect the skills of artisans through two centuries. The lettering is well-drawn and spaced with machine-like precision. The designs and devices that appear on the cards are direct and eye-catching. These early cards belonged primarily to those in professions or those of the merchant class. Their designs were created to appeal to the educated classes.

Many of the early trading cards show the influence of Thomas Chippendale, especially his work in the popular Chinese style. This was especially true once the public menace of ornate hanging signs to denote a business location was replaced with the street numbering of addresses around the year 1762. The focus of the cards also changed. The script of the cards came to include the type of goods advertised and directions to the establishment.

Richard Severn, Jeweller and Toyman

The corner of Paul’s Grove-Head-Court

near Temple Barr, London

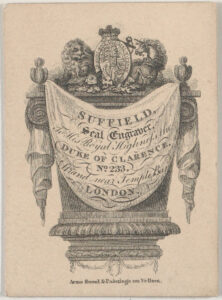

John Suffield was an engraver and desiger of lettering, although he was also known through his signed metal work and made a medal commemorating the election of Sir Charles Cockerell to Evesham in 1819. Suffield is also listed in the 1817 Johnstone’s London Commercial Giude, and Street Directory.

John Suffield was an engraver and desiger of lettering, although he was also known through his signed metal work and made a medal commemorating the election of Sir Charles Cockerell to Evesham in 1819. Suffield is also listed in the 1817 Johnstone’s London Commercial Giude, and Street Directory.

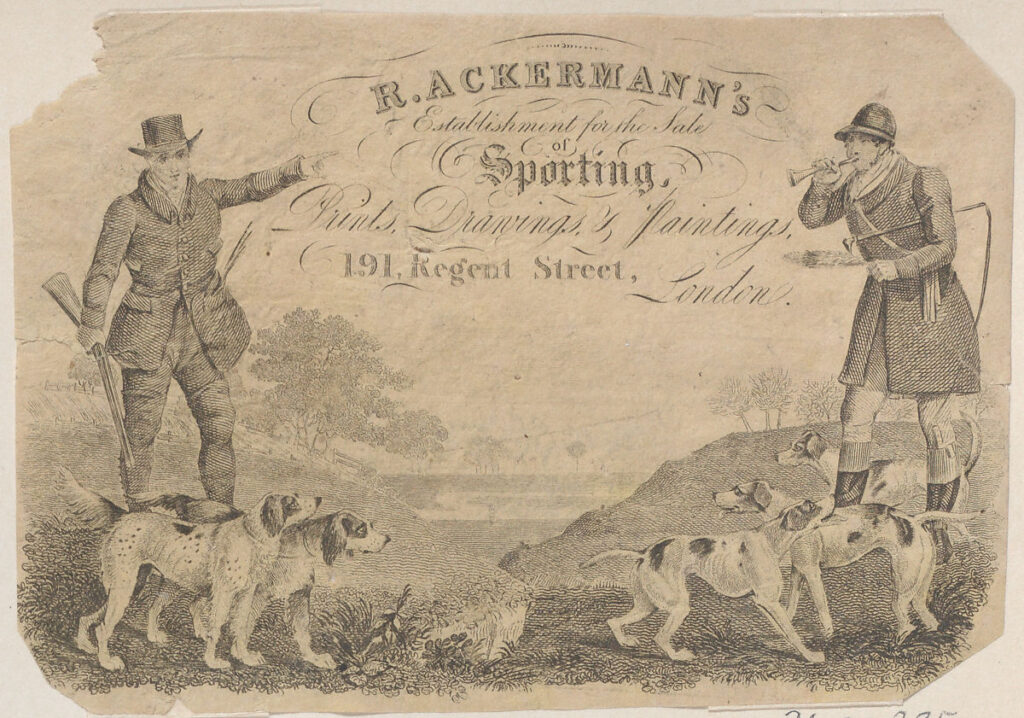

Trade Card for R. Ackermann, Printseller and Art Dealer

For those who want to learn more on this intriguing subject I suggest the book:

London Tradesmen’s Cards of the Eighteenth Century by Ambrose Heal.

If you are interested in the role trade cards have played in discovering the role of women in business in 18th and 19th century England, stay tuned. I will be adding a post dedicated to that subject quite soon!