by Victoria Hinshaw

Just before closing for the covid 19 pandemic, New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art reopened the British Galleries after a total reinstallation. When was last in NYC, I was disappointed not to visit favorite spots such as the Lansdowne House Dining Room, removed from the London structure and brought to the Met many years ago. But now that room and many other treasures have been restored, reinstalled, and reinterpreted.

I have not visited the new Galleries (the Met is scheduled to reopen in late August), but they have received widespread comments from art and cultural sources, enough to give us a pretty good idea of the new approaches.

From the Met’s press release last March, 2020: ‘The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s $22m reinstallation of its British galleries opens to the public on Monday with a stirring narrative on the anxious commercial striving that shaped the British decorative arts from 1500 to 1900. Featuring nearly 700 works in 10 rooms spanning 11,000 sq. ft, the galleries tell a warts-and-all story of empire in which dark elements like the slave trade emerge and cataclysmic events like the Great Fire of London in 1666 serve as dramatic punctuation points. Nearly a third of the works on view have been newly acquired, with a preponderance of those recent purchases in the 19th-century section.’

In the above picture, a bust by Sir Francis Chantrey (1781-1841) of Arthur Wellesley, lst Duke of Wellington (1769-1852), is at the left and below. At right and below is a portrait of George (1762-1830), Prince of Wales, later George IV, by Sir William Beechey (1753-1839). Beneath the portrait is a red bench by Thomas Hope (1769-1831), before 1807.

Other than these familiar objects, the installation is very different than past representations of British Art. Again, quoting the Met’s press release: ‘The Met’s British collection is the largest of its kind in the US. The opening, part of the Met’s 150th anniversary celebrations, crowns a seven-year effort that began with the notion that “these galleries needed some attention and refreshment,” says Wolf Burchard, the Met’s associate curator of British furniture and decorative arts. “The previous galleries were all about the individual objects in historic interiors, and there was no thread that went through it,” he explains. “The new galleries are all about the cross section between creativity and entrepreneurialism.”’

The Met continues: ‘The first gallery, clad in paneling made for the merchant trader William Crowe, opens from the museum’s medieval sculpture hall, vaulting the viewer into the 16th-century Renaissance era. A wall text emphasizes how the House of Tudor competed to match the artistic splendors of papal Rome, the French courts and the Germanic centers of Hapsburg power, and how a new class of professionals with luxury appetites arose under the stable reign of Elizabeth I amid an expansion of global trade. Surveying the gallery from its perch is a polychrome terra cotta bust that is thought to depict Bishop John Fisher, who was executed for opposing Henry VIII’s decision to lead the Church of England away from Roman Catholicism and papal authority. Leading to a mezzanine is another highlight, the magnificently ornamented and newly conserved pine and elm staircase from Cassiobury Park, Herfordshire (around 1677-80), with its naturalistic acanthus leaves, acorns, birds and snakes.’

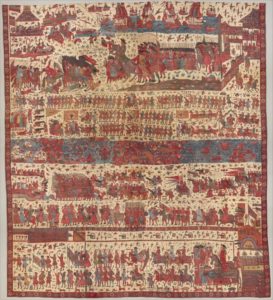

The Met continues: ‘A gallery titled “Tea, Trade and Empire” drives home how four commodities—tea, sugar, coffee, and cocoa—fuelled artistic innovation in Britain from the late 17th through the late 18th century. The museum has installed two towering semi-circular glass cases filled with a whimsical assortment of 100 teapots, underlining how that staple became a pivot point for social interaction in even modest British households and nurtured an enormous national ceramic industry. (The galleries are mindful not just of an aristocratic elite but of multiple layers of society.) At the same time, the 1789 title page of a slave’s memoir on the perimeter of the gallery alerts viewers to the exploitative nature of empire, with the trans-Atlantic slave trade rising in tandem with the spread of sugar plantations. “Much of the wealth of this period is built on the labor of enslaved Africans,” a wall text says simply.’

The Met continues: ‘Three galleries are devoted to the re-creation of striking 18th-century British interiors moved from Kirtlington Park (Oxfordshire), Croome Court (Worcestershire) and Lansdowne House (London). A wall text notes that the Lansdowne dining room, designed by Robert Adam and crowned by an intricately decorated ceiling, banished odor-absorbing textiles that would have retained “the smell of the victuals”.’

Last year I was at the Met in July but I won’t make it this year. What a strange year 2020 is!