by Guest Blogger Marilyn Clay

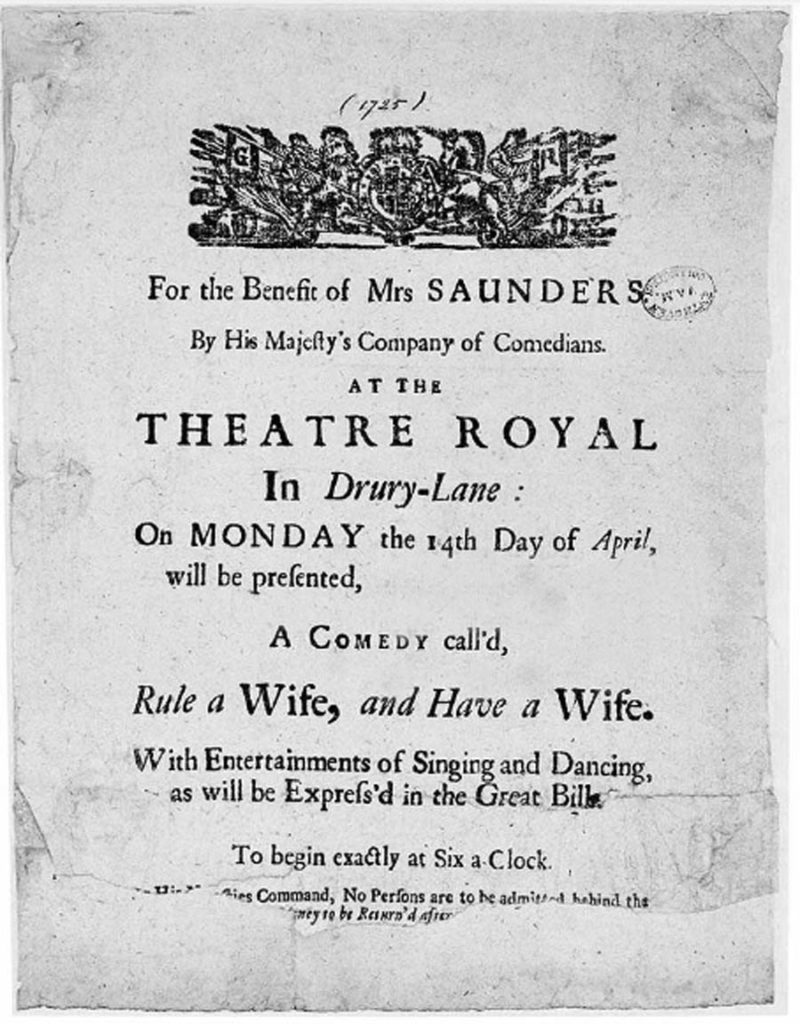

During the Regency period, attending the theatre was a passion shared by nearly everyone from London’s aristocratic upper ten thousand down through the middling classes and the lower orders, i.e. those whose lives consisted mainly of serving their betters. Only a few playhouses in England were approved by the king. Those theatres so blessed were known as Patent Theatres and were thereafter distinguished as being a Theatre Royal. Non-patent theatres were prohibited from producing serious drama and had to limit their performances to farce or light comedy. To avoid fines, closure, or prosecution theatres unapproved by the king took to including singing and dancing within their dramatic productions, including Shakespearian plays!

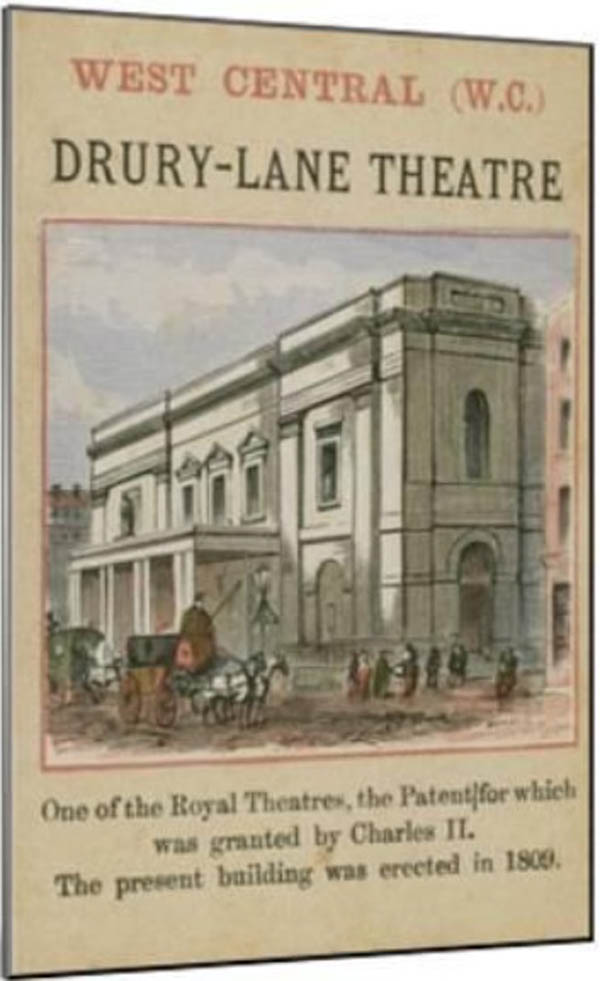

London’s premier patent theatres, Drury Lane and Covent Garden, were both also granted permission to remain open throughout the winter months, meaning for them, the theatre season ran from mid-September through mid-June. Another London patent theatre, Haymarket was mainly a summer playhouse open from May to early autumn.

Unfortunately, none of London’s theatres at this time were immune from disasters ranging from fire and bankruptcy to contentious and often public disagreements amongst its management and performers. In 1803, the patent theatre Covent Garden was the theatrical home of the famed actor John Philip Kemble and his sister, the equally famous actress, Sarah Siddons, who had been lured away from Drury Lane. After Covent Garden burned to the ground in 1808, performances were staged at the Italian Opera House in summer and the Haymarket in winter. A year later, when Covent Garden reopened, touting a new tier of private boxes, the higher ticket prices, instituted to finance the rebuilding and renovation of the theatre, resulted in what became known as the ‘Old Price’ riots as angry patrons protested. The riots continued for sixty nights and were so intense that on one occasion, the noise drowned out Kemble’s performance of Macbeth.

The patent theatre, Drury Lane, located between Bridges and Russell Streets in London, claimed to be fireproof, yet, in February 1809 it, too, burned to the ground. The theatre was eventually rebuilt and reopened in October 1812. In the interim, performances were staged at the Lyceum and Haymarket theatres. Two years later in 1814, Drury Lane was once again remodeled with the popular poet Lord Byron serving on the management board. Drury Lane’s most famous manager was the playwright Richard Sheridan, who on the day the theatre burned was observed sipping a glass of port as he watched the flames viscously devour the building. In his defense, Sheridan remarked, “Surely a man may enjoy a glass of wine before his own fireside.”

For the first ten years of the century, one of Drury Lane’s most sensational actresses was Dorothea Jordan, who for two decades was mistress to the Prince Regent’s brother the Duke of Clarence, the future King William IV. Though the pair never married, during their time together she bore him ten children, all of whom took the surname FitzClarence. Mary Robinson was another sensational Drury Lane actress who became the Prince Regent’s first mistress, he at the time being a mature gentleman of seven and ten. Historians differ as to whether or not theirs was a full-fledged love affair, but the fact that love letters were exchanged and assignations were made and kept was enough to set tongues wagging. That the affaire ended badly was not disputed.

In the latter years of the Georgian era, the King’s Theatre, located at the corner of Pall Mall and Haymarket in London, was essentially the home of the opera. Because most all operas at this time were sung in Italian, the King’s Theatre became known as the Italian Opera House. Lavishly decorated, the Opera House catered to an exclusive and aristocratic audience. Boasting five tiers of private boxes, one could rent a box for the entire season for a mere three hundred guineas. Declared the Times in 1808, “The boxes are painted within sky blue . . . the curtains are scarlet and match the seats of the pit. The boxes belonging to the Royal Family are all lined with scarlet drapery. The ceiling exhibits a beautiful mythological painting of Aurora in the centre.” Said the visiting Persian Ambassador Abul Hassan, “[It is] nothing like I have ever seen before; it has seven magnificent tiers all decorated in gold and azure, and hung with brocade curtains and paintings.” Not everyone found the décor quite so lovely. “In spite of the brilliant lighting, it is over-decorated with paintings,” said foreign visitor Joanna Schopenhauer. “. . . in rather poor taste with hosts of little cupids swarming everywhere amidst thousands of scrolls and garlands.” In 1818, gaslight was added to the interior of the Opera House, although the use of candles for lighting was not entirely abandoned until a good many years later.

Amongst the non-patent theatres of this period was the Pantheon located in Oxford Street. Permanently closed in 1814, it reopened a decade later as a shopping bazaar. The Regency Theatre, named in 1811 in honor of George, the Prince of Wales becoming Regent, was situated in Tottenham Street and was formerly a riding academy. In 1800, the Royalty Theatre, located in Wellclose Square, was owned by Philip Astley, a former cavalry officer whose equestrian spectacles drew large crowds. During his winter season, Astley staged his circuses at the Royalty, which was later renamed the East London Theatre. In 1806, Astley began staging his productions at the Olympic Theatre in Wych Street, which caused that venue to become known as Astley’s Pavilion.

Also at this time, a good many provincial theatres could be found in other English towns and villages such as Bath, Brighton, Bristol, Margate, Dover, Maidstone and Plymouth where both itinerate acting companies, and visiting thespians, regularly performed.

The following is a brief compendium of early theatre terms:

Tokens – were used in place of tickets, which at the time did not exist. Theatre-goers instead purchased special round or oval-shaped tokens made from bone, ivory or even silver. Tokens were purchased for the duration of one or two seasons. Since theatre seats were not yet numbered, a patron’s name and the number of his personal theatre box might also be engraved upon his individual token.

Theatre Lights – consisted of lit candles placed in hanging chandeliers that were suspended over the heads of the audience. Because candles could not be dimmed during a performance, it was not uncommon for a dribble of hot wax to drop down upon a theatre-goer’s head or arms causing the patron to cry out, or shriek in pain. The stage was lit by oil lamps hanging in the wings with smaller lamps placed along the outer rim of the stage. Since the auditorium was constantly lit, patrons could easily observe one another as well as the performers on stage. Patrons often talked back, or called out, to performers, or to those seated in the pit, which contained row upon row of backless, unpadded benches.

The Second Seating – A stream of patrons were let into the theatre often upon the conclusion of the first act, which is when the price of admission was reduced. To avoid paying full price, many less affluent patrons waited outdoors until the price of admission fell, often by half.

The Gallery – that area of the theatre also known as the Gallery. Located high above the private boxes, the auditorium, and the pit (ground level), the gallery is where the common folk, or servants of the wealthy, sat.

Fop’s Alley – an aisle on the pit level where rakes and dandies liked to parade.

Orange Girls – were young peasant girls who sold oranges to patrons. It was said that Nell Gywn, a famous actress who later became the mistress of King Charles II, began her career in the theatre as an orange girl before she became a well-known stage performer.

Playbills – were posted in nearby inn and coffee house windows. Orange sellers might sell them to patrons in place of a program before a play commenced.

Costmes – Despite a well-established theatre’s stock wardrobe, players were expected to provide their own costumes, although leading thespians were often given a special stipend to be used especially for that purpose.

Afterpiece – following a serious drama, or a double bill of plays, a light farce or pantomime called the ‘afterpiece’ was staged. A full ballet was generally performed following the completion of an opera. Given the length of plays and operas at the time, a night at the theatre truly meant a full night spent at the theatre!

~ ~ ~

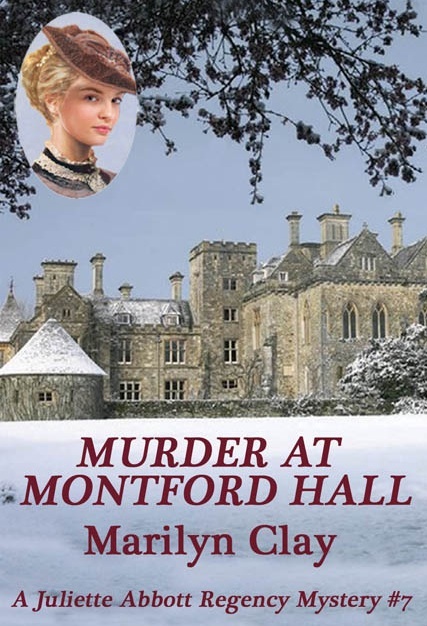

MARILYN CLAY, former founder and publisher of The Regency Plume, an international newsletter focused on the Regency Period in English history, is now the best-selling author of over two dozen fiction and non-fiction books. Marilyn’s popular Regency-era mystery series features Miss Juliette Abbott as the clever young sleuth who always manages to run the criminal to ground, often at great peril to herself, or her intrepid young lady’s maid Tilda.

Marilyn Clay’s newest title in her Juliette Abbott Regency Mystery Series, Murder At Montford Hall, is now available in both print and Ebook from all major online retailers. In this seventh book of the series, a group of London’s formerly famous theatrical personages find themselves stranded at Montford Hall during a blinding snowstorm. When it appears that someone is attempting to kill them all off one-by-one, tempers flare out of control as the terrified thespians point fingers at one another. Found standing over the dead body of a beloved actor, Miss Abbott is instantly declared the guilty party, but can she run the real murderer to ground before the company of angry houseguests take matters into their own hands?

Other titles in Marilyn Clay’s Juliette Abbott Regency Mystery Series include, Murder At Morland Manor, Murder In Mayfair, Murder In Margate, Murder At Medley Park, Murder In Middlewych, Murder In Maidstone, and now Murder At Montford Hall.

You can purchase Murder At Montford Hall from Amazon, Apple, or Barnes & Noble online. All seven title are also available from Scribd, Kobo and others. Visit Marilyn Clay’s Amazon Author Central Page, or Marilyn Clay Author.