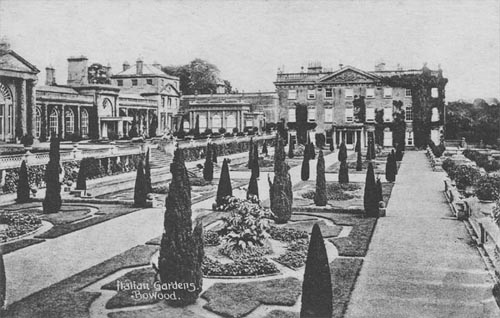

As part of the itinerary for the Georgian Tour this past April, our group spent a day at Bowood House, home to the Marquesses of Lansdowne since 1754. Actually, that’s a bit of a misnomer – the original Bowood House was demolished and the Grade I listed Orangery converted to a family home. Compare the photo above to those below:

The Bowood estate was originally part of the forest of Chippenham and belonged to the Crown until the early 18th century, when construction of a house was begun on the ancient site of a hunting lodge. The first Earl of Shelburne purchased the unfinished property in 1754 and enlarged the house. His son, the 2nd Earl and first Marquess of Lansdowne, hired famed Scottish architect Robert Adam (who had designed Lansdowne House in London) to further enhance the house and build an adjacent orangery and a menagerie. Adam also built a mausoleum for the 1st Earl in the extensive parklands surrounding the house. In the 1770s, the two parts of the house at Bowood (the “Big House” and the “Little House”) were joined together by the construction of an enormous drawing room.

From Wikipedia: “In World War I, the 5th Marchioness set up an auxiliary Red Cross hospital in the Orangery. During World War II, the Big House was first occupied by a school, then by the Royal Air Force. Afterwards it was left empty, and by 1955 it was so dilapidated that the 8th Marquess demolished it, employing architect F. Sortain Samuels to convert the Little House into a more comfortable home. But before it was demolished, the Adam dining room was auctioned and bought by the Lloyd’s of London insurance market, which dismantled it and re-installed it as the Committee Room in its 1958 building. The room was subsequently moved in 1986 to the 11th floor of its current building, also on Lime Street in the City of London.”

The visitor’s approach to the House is through a portion of the Capability Brown designed landscape and once again, we had glorious weather –

The Italianate terrace gardens on the south front of the house were commissioned by the 3rd Marquess. The Upper Terrace, by Sir Robert Smirke, was completed in 1818, and the Lower, by George Kennedy, was added in 1851. Originally planted with hundreds of thousands of annuals in intricate designs, the parterres are now more simply planted.

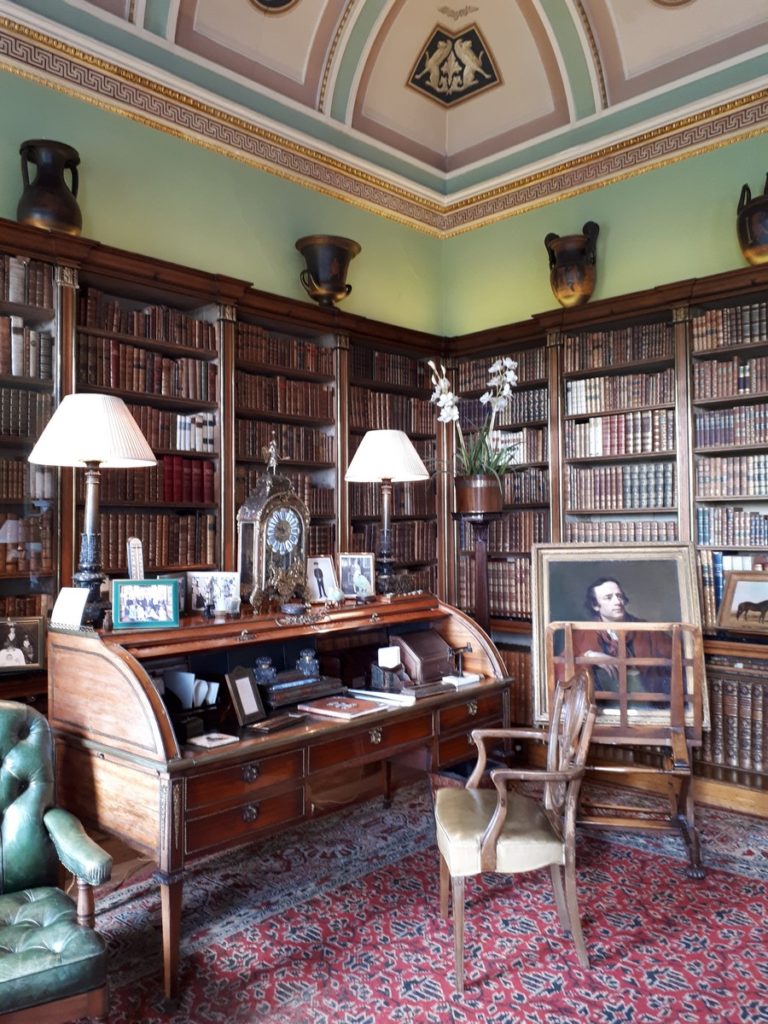

Nearly 300 years worth of amazing artifacts and antiques from the family history are on display in the house, but of course, my favourite room was the library.

Above, the family Chapel, located in what was once the laboratory where Joseph Priestley discovered Oxygen in 1774.

Note the decorative door knob and keyhole covers above.

One of the most recognizable items on display at Bowood is Lord Byron’s Albanian costume. Margaret Mercer Elphinstone, daughter of Admiral Lord Keith, was a close confidant and correspondent of Princess Charlotte of Wales (daughter of the Prince Regent, later George IV). After the Princess died in 1817, Meg married the Comte de Flahault, who served as an Aide-de-camp to Napoleon. Meg, an heiress both from her father and her late mother, was well known in Regency-era society. Another good friend was the poet Lord Byron, who gifted Meg with the Albanian costume in which he was famously painted about 1813. Meg was also portrayed in the outfit, that engraving also being on display at Bowood. So how did the original costume come to be at Bowood? Emily de Flahault, daughter of the Comte and Meg, married the 4th Marquess of Lansdowne and was mother to the 5th Marquess.

Several more examples of historic costume are also on display.

Family items in the Bowood collection included jewelry, swords, china and more, but personally, I found this portrait miniature fascinating, as I’d never seen another like it before. I’ve since learned that this type of portrait miniature (above and below) was known as a transformation miniature and featured multiple mica discs that in effect allowed one to change the costume worn by the sitter. From The Royal Collection Trust website: “The mid-seventeenth century saw a vogue for an unusual type of miniature which could be dressed in a variety of different outfits by placing painted transparent overlays on top of the master image. Constructed from very thin slices of the mineral mica, these overlays included male and female outfits with appropriate accessories. When placed on top of the portrait, these semi-transparent discs transformed the costume and hairstyle of the sitter, creating a new composite picture, much like outfitting a modern paper doll. It seems likely that the purpose of such a set was to provide entertainment.”

Once again, a fabulous time was had by all at Bowood, but the day wasn’t over yet –