I have a great friend in Beth Elliot. Those of you who follow this blog and my posts on Facebook will know that Beth and I try to get together whenever I’m in England. And you may recall that Beth was my saviour when my phone was stolen in London, taking me to buy a new one and following that up with a fabulous day out in Greenwich. This time over, Victoria Hinshaw and I spent a few days doing research on the Duke of Wellington at the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL), located in Reading.

As it turns out, Beth lives just outside of Reading, in the very same town in which our hotel was located. Needless to say, we had the opportunity to see each other often. What does need to be said is that Beth went out of her way to accommodate Vicky and myself, picking us up at the train station, driving us where we needed to go, joining us for dinner nightly and taking us to hidden villages and places of interest on our days off. She was even kind enough to bring us back to her home on several occasions, giving us lunch, wine, laughs and the opportunity to see her fabulous garden and to unwind in her incredibly comfy front room.

Since Beth, Vicky and I first met in 2010, during Number One London’s Duke of Wellington Tour, she and I have shared personal histories and family stories, and I was most enchanted with her stories of her beloved Uncle Frank, who was Financial Editor for the Times. Frank Wright was born in 1900 and graduated from Manchester University before joining the staff of the Manchester Guardian, moving in 1924 to it’s London office as Assistant Chief Editor, going on afterwards to join the Times of London.

What I knew about Uncle Frank was that he and his wife, Auntie Marie, had never had children of their own and so looked upon Beth as a most favourite niece. Beth spent many hours with Uncle Frank and Auntie Marie, but what sticks in my mind most are Beth’s stories of going with Uncle Frank to his London office. Once the day’s business was done, Uncle Frank would ask Beth what she most wanted to do, and would then grant her wishes, regardless of the fact that most of the places she chose were at opposite ends of London. Off they’d go, Uncle Frank indulging the wishes of his favourite little girl and Beth enjoying his undivided attention.

So, when Beth mentioned during our last visit that she had some things of Uncle Frank’s she was set to take to the charity shop, I had to ask –

“Wait. What? What sort of things?”

“Oh, just some old clothes. I’ve got a Chinese robe he bought in the 30’s at Harrods.”

“Wait. You’re giving Uncle Frank’s 1930’s Chinese robe from Harrod’s to the charity shop?!”

“Do you want to see it?”

“Er. Yes!”

Off she went, up the stairs and back down. “I have this, too,” she said, laying a treasure on the table before me.

“It’s Uncle Frank’s cigarette case,” she said.

“And it’s leather. And embossed with his initials.” Upon opening it, I saw the Harrod’s stamp. I picked it up and inhaled the smell of leather and tobacco.

“Would you like it?” Beth asked.

“What? Don’t you want it?”

“I don’t smoke. And besides, what am I ever going to do with it. If you think you can use it, please take it.”

I stared at her. Stunned. “I don’t smoke, either. But I’d love to have it. Are you sure?”

“Yes. I’ve got to have a clear out. And here’s the robe I told you about.”

“Try it on,” Beth urged.

Silently I prayed, please, Uncle Frank, be the same size as me. Please. I slipped the robe on and . . . it fit. Like a glove.

“I love it,” said I, looking at myself in the mirror and running a hand over the black silk lapel. “How does it look?”

“It looks fabulous on you,” offered Vicky.

“Do take it if you want it,” said Beth. “It’s only going to be given away otherwise.”

“I can’t believe you’re giving this away.”

“I can’t believe you want it,” said Beth. “Hang on, I’ve got some other bits if you want to see them. Come with me out to the garden, they’re in the shed.”

In the shed?!

After a quick rummage, Beth came out with a rather large box, which held a morning suit – tailed jacket, waistcoat and striped pants. Even a pair of spats.

Holding out the jacket, Beth said, “Here, give it a try.” I took it from her and attempted to get into it. Dash it all, it didn’t fit.

“It’s too small!” I lamented.

“It isn’t,” Beth said.

“There’s no way I can get it on,” I wailed.

“Here, give it to me,” Beth said, in her no nonsense way. “Now, you stand there and I’m going to slip it on you. You don’t think Brummell got into his coats without help, do you? Gentlemen needed a valet to don their coats. Turn your back to me and put your arms down at your sides and I’ll slip this on you.”

I complied, doubtfully. Beth slid the coat sleeves up over my arms, gave it a yank and settled it upon my shoulders. “There. I told you it would fit. Go look in the mirror.”

I obeyed. Reader, it fit. As though it had been tailor made for me.

“Wow,” said Vicky.

“How does it look?”

“Wow,” repeated Vicky. “Do you like it?”

“Like it?! I love it.”

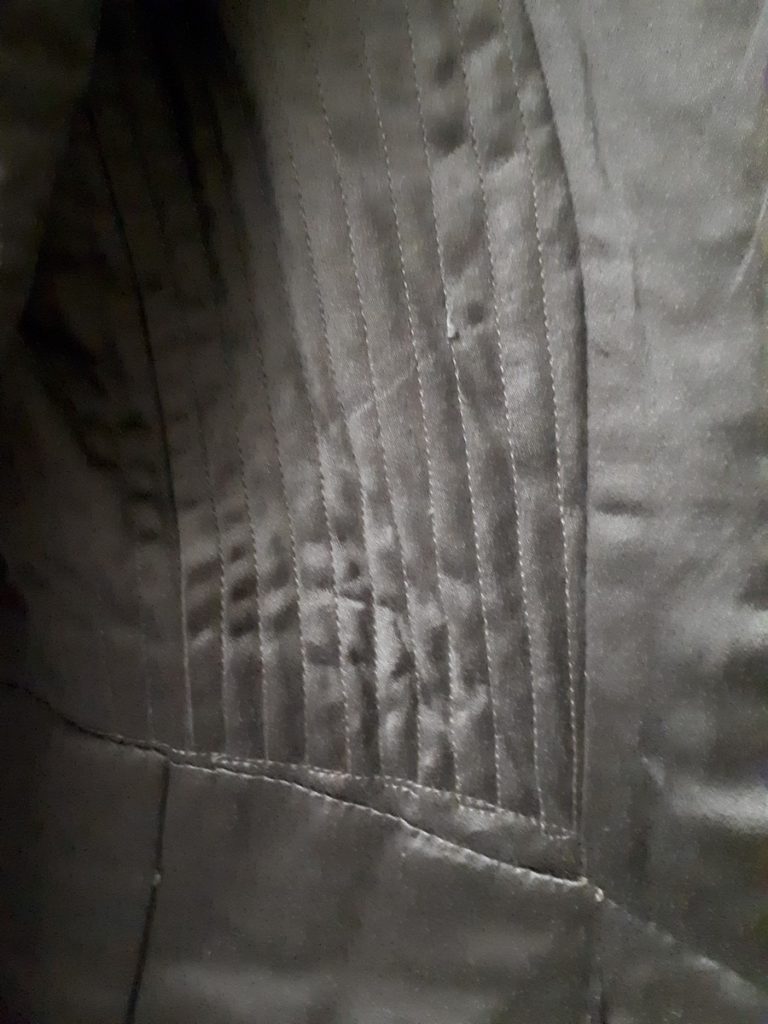

“Here, take the waistcoat, too,” offered Beth. It, too, fit like a dream. Once I’d removed the coat, Beth directed my attention to the construction details inside, gorgeous attention to detail and quilting that had gone out of fashion many decades ago.

“Try the pants on,” suggested Beth. I did, but while Uncle Frank and I seemed to be the same size from the waist up, we varied widely from the waist down. Or it was the style of the striped trousers that defeated me – I looked like a clown in the baggy trousers.

“No,” said Beth, “those won’t do. But there are a few final things you must see.”

I didn’t care about anything else. The robe and coat were each beyond my wildest dreams. But who was I to say no?

This time, she came through with a hat box. Opening the lid, we found a leather collar box and, upon opening that, we discovered that it still held a number of collars, as well as collar and cuff studs. Beneath that was a gentleman’s white silk dress scarf. And under that were the hats. Three hats. And what hats they are!

“Try them on,” Beth prompted. After a stunned moment, I lifted the first hat, a derby, and put it on. Again, it fit as though it had been made to fit my head alone. Then there were two top hats, one a traditional beaver hat, the other a silk, collapsible opera hat. Each one fit. And looked deuced fine atop my head, if I do say so myself.

“Do you think you can fit this all into your suitcase?” Beth asked, once I’d left off admiring myself in the mirror.

“Never. We’ll have to ship it. Are you absolutely certain that you want me take it all?” I asked. “I mean, I know what Uncle Frank meant to you.”

“Uncle Frank would be thrilled that they were being given to someone who can enjoy them. Believe me, you’re doing me the favour by allowing me to clear all this out of my attic and shed. I just can’t believe that you actually want it all. I’ll go and fetch a box and we can pack these up.”

While Beth was gone, Vicky asked, “What in the world are you going to do with all that suff?”

“I’m going to wear it. At writer’s conventions and seminars. And maybe on Sundays. All my costuming needs have been taken care of in one fell swoop!”

My costuming needs had been take care of, and not only by Uncle Frank. I had found the beauty below in a charity shop in Bath for twenty quid before meeting up with Vicky and Beth.

Next day, Beth boxed up my treasures – and tied up the boxes with string. I’ll let you digest that for a bit. String. A lost art. I could wax lyrical and write an entire post about the string, but I’ll spare you. Shortly thereafter, Beth and I walked down to her local Post Office and shipped the boxes off to my address in America. And they both arrived long before I made it home.

I’m thrilled to report that all of Uncle Frank’s clothing has now been dry cleaned and they are hanging in my closet, just waiting for their first airing at the upcoming Romance Writers of America (RWA) Conference in Denver. Now all I need is a valet.

Wonderful! These are treasures. Each garment is a work of art, and Lock and Co was the most celebrated of all London hatters. You can enjoy wearing them or they would make perfect costumes for a production of a Noel Coward play.