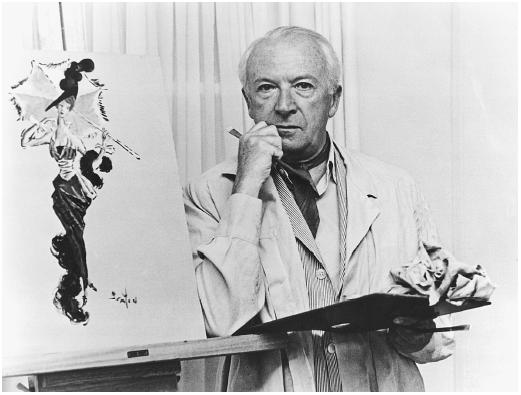

In my continuing quest to broaden my knowledge of those people who lived during Britain’s between wars years, I recently read Self Portrait With Friends: The Selected Diaries of Cecil Beaton 1922 – 1974, edited by Richard Buckle. Beaton was one of the constants in many of the other period diaries and letters I had read, and no wonder. He had a ringside seat to much that happened in Britain from the 1920s right through to his death in 1980. Beaton was the photographer of the day, any day, working with both Vogue and Vanity Fair magazines for decades, as well as for the Ministry of War during WWII. In addition, he was the official Royal photographer for decades, which of course likewise made him the photographer of choice for socialites, actors and aristocrats, many of whom became Beaton’s friends. Last year, I was fortunate enough to see the retrospective exhibition, Never A Bore: Deborah Devonshire and Her Set by Cecil Beaton at Chatsworth House.

Before long, Beaton’s drawing talents and his innate sense of style and taste brought him work as both a set and costume designer for ballet productions, stage plays and films, earning him Tony Awards and Academy Awards for Best Costume Design and Best Art Direction for both GiGi and My Fair Lady.

Beaton’s diaries were published in several volumes during his lifetime, and Self Portrait With Friends: The Selected Diaries of Cecil Beaton 1922 – 1974 is a selection of entries from all volumes, a taster of the Beaton diaries, if you will, some examples of which you’ll find below. It was a satisfying introduction to the diaries, which I plan to go on to read.

Autumn 1935

“Though nothing about Mrs. Simpson appears in the English papers, her name seems never to be off people’s lips. For those who enjoy gossip she is a particular treat. The sound of her name implies secrecy, royalty, and being in the know. As a topic she has become a mania, so much so that her name is banned in many houses to allow breathing space for other topics. . . five years ago I met Mrs. Simpson in a box with some Americans at The Three Arts Club Ball . . . Mrs. Simpson seemed somewhat brawny and raw-boned in her sapphire-blue velvet. Her voice had a high nasal twang. . . About a year ago, I had an opportunity to renew acquaintance with Mrs. Simpson. I liked her immensely. I found her bright and witty, improved in looks and chic.

“Today she is sought after as the probable wife of the King. Even the old Edwardians receive her, if she happens to be free to accept their invitations. American newspapers have already announced the engagement, and in the highest court circles there is great consternation. It is said that Queen Mary weeps continuously.”

1940

12 October

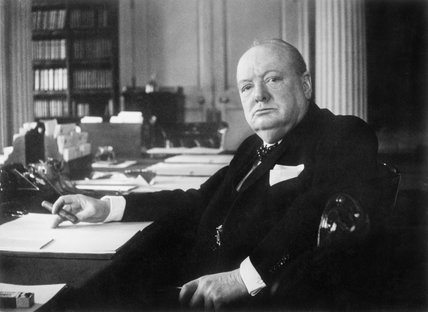

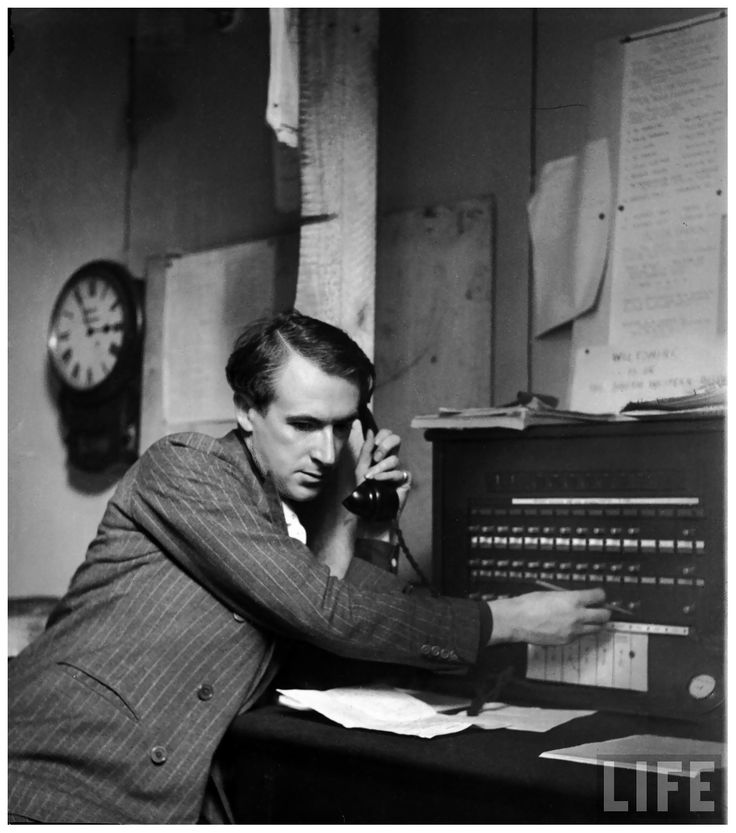

“James (Pope-Hennessy) is writing a book called History Under Fire for which I am doing the photographs. Besides the vandalistic damage, we must show the tenacity and courage of the people, and we do not have to look far. . . Londoners have had one month of this so far, and they must look forward to a whole winter of it . . . By degrees many people have grown accustomed to being frightened. For myself, most evenings I have beetled off to the Dorchester. There the noise outside is drowned with wine, music and company – and what a mixed brew we are!”

30 December

“The city was still in flames after last night’s raid when eight Wren churches and the Guildhall were destroyed . . . In the biting cold with icy winds beating around the corners, James P.H. and I ran about the glowing smouldering mounds of rubble where once were the printers’ shops and chop houses of Paternoster Row . . . We went to St. Paul’s to offer our prayers for its miraculous preservation. Near the cathedral is a shop that has been burned unrecognizably; in fact, all that remains is a arch that looks like a vista in the ruins of Rome.

“Through the arch could be seen, rising mysteriously from the splintered masonry and smoke, the twin towers of the cathedral. It was necessary to squat to get the archway framing the picture. I squatted. A press photographer watched me and, when I gave him a surly look, slunk away. When I returned from photographing another church, he was back squatting and clicking in the same spot I had been. Returning from lunch with my publisher, my morning’s pictures still undeveloped in my overcoat pocket, I found the press photographer’s picture was already on the front page of the Evening News.”

“Diana has bought a cow called Princess – a female equivalent of Ferdinand, for there never was so clinging and affectionate an animal as Princess. Twice a day Diana milks her, at 7:30 a.m. and 6 p.m. Princess delivers enough milk to keep the household and to make one large cheese every other day. The goat, less docile, produces milk that makes equally good cheese. Diana’s hens produce ten eggs a day . . . . The latter part of the morning is spent in the dairy with large bowls of blue and white china, butter muslin nets and spotless efficiency. Here she sets about the technical jobs of cutting whey, taking temperatures and heating to certain degrees large bathtubs of milk, which with the addition of rennet drops from a calf’s innards will eventually be turned into the required number of cheeses and arranged in rows on the storeroom shelf.”

8 Pelham Place, London: September 1944

“The flying bombs and those beastly V2s, exploding from out of nowhere, have created new havoc in London since I left for the Far East nearly a year ago. . . War in England is more total than ever, hardships always increasing. People look terribly tired and tend to be touchy and quarrelsome about small things.

“Yet, in spite of all the horror and squalor, London has added beauty. In its unaccustomed isolation above the wastes of rubble, St. Paul’s is seen standing to supreme advantage, particularly splendid at full moon. The moon in the blackout, with no other light but the stars to vie with, makes an eighteenth-century engraving of our streets. St. James’s Park, without its Victorian iron railings, has become positively sylvan.

“Even in the centre of the town there are aspects of rural life. While the buses roar along Oxford Street the gentler sounds of hens and ducks can be heard among the ruins of nearby Berners Street. There are pigs sleeping peacefully in improvised styes in the craters where seeds that have been buried for three hundred years have propagated themselves and make a display of purple milk-wort and willow-herb. The vicar of St. James’s, Piccadilly, counted twenty-three different varieties of wild plant behind his bombed altar.”

3 July, 1963

“Geoff Allan, a burly somewhat top-heavy-looking youth from the outskirts of London, has become an expert at ‘ageing’ clothes. Today he was breaking down Eliza’s little jacket in which she first visits Higgins’ house. Everyone who had seen the coat in a test agreed that the black velveteen appeared too elegant and rich-looking. In an effort to save the garment, Geoff decided to take drastic measures. He asked me, ‘Suppose it doesn’t survive?’ ‘Go ahead. At worst, we’ll have to get a new one.’ Geoff put the coat in a boiling vat. After a few hours the black velvet had become a cream colour. Geoff now started to make the coat darker. Putting a spoon in dye, he smeared its surface, leaving light patches where the sun might have faded the collars and shoulders. He purposely left paler the material at the edges and in the creases. The coat was then dried out in a furnace. To me, it now looked like something found in an ancient Egyptian tomb: it was hard and brittle and brown as poppadom. With blazing eyes, Geoff then brought out a wire brush and gave the garment a few deft strokes, saying, ‘This bit of pile will soon disappear.’ It did. Later Geoff said, with avid enthusiasm,, ‘I’ll take the thing home tonight and sew frogs on it again – coarsely, with black thread, and I’ll sew them with my left hand. Then, with my right hand, I’ll rip then off. Then I’ll knife the seams open here as if it’s split. Afterwards, with coarse thread, I’ll patch it. Of course, the collar will have to be stained a bit as if Eliza had spilled coffee on it (no, she would drink tea . . . it will have to be tea stains), and there must be greasy marks on the haunches where she wipes her dirty hands. Naturally the skirt will have to be made muddy around the hem, because, you see, she sits when she sells her violets, and the skirt, and petticoats also, would seep up the wet.”’

11 April 1966

“So Evelyn Waugh is in his coffin. Died of snobbery. Did not wish to be considered a man of letters, it did not satisfy him to be thought a master of English prose. He wanted to be a duke, and that he could never be; hence a life of disappointment and sham. For he would never give up. He would drink brandy and port and keep a full cellar. He was not a gourmet, like Cyril Connolly, but insisted on good living and cigars as being typical of the aristocratic way of life. He became pompous at twenty and developed his pomposity to the point of having a huge stomach and an ear trumpet at forty-five.

“Now that he is dead, I cannot hate him; cannot really feel he was wicked, in spite of his cruelty, his bullying, his caddishness. From time to time, having appeared rather chummy and appreciative and even funny (though my hackles rose in his presence), he would suddenly seem to be possessed by a devil and do thoroughly fiendish things. His arrogance was at its worst at White’s. Here he impersonated an aristocrat, intimidated newcomers and non-members, and was altogether intolerable. But a few loyal friends saw through the pretence and were fond of him.”

January 1970

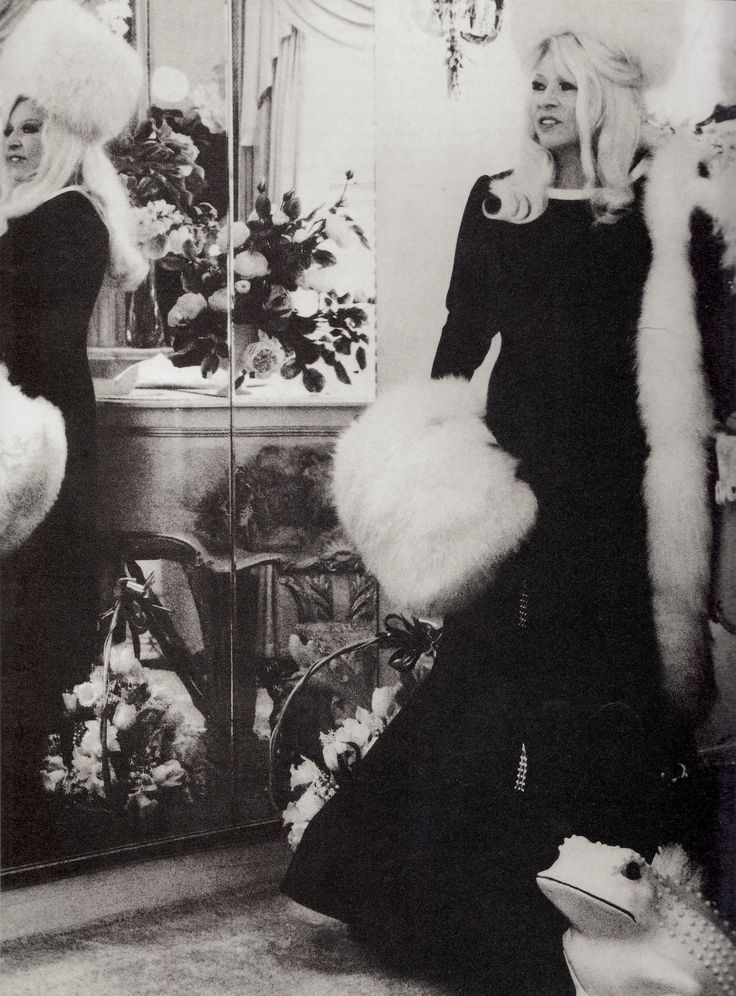

“On arrival in Hollywood at the huge 1920s cement apartment block which Mae West owns, I was surprised to find how small her personal quarters are. To begin with I was fascinated; white carpets, pale yellow walls, white pseudo-French furniture with gold paint, a bower of white flowers, huge ‘set’ pieces of dogwood, begonias, roses and stocks – all false.

“The piano was painted white with eighteenth-century scenes adorning the sides, a naked lady being admired by a monkey as she lay back on draperies and cushions. . . Dust covering everything . . . She seems quite contented, or so it appeared from my short glimpse of her during the afternoon photographic session. Miss West’s entourage consisted of about eight people from the studio, her own Chinese servant, and her bodyguard, Novak, an ex-muscleman. . . She had put on weight over the holidays and her dresses would not fit. She was rigged up in the highest possible fantasy of taste. The costume of black and white fur was designed to camouflage every silhouette except the armour that constricted her waist and contained her bust.”

September 1970

“Went to the house in the beautiful Bois de Boulogne to have tea with the Duchess of Windsor. On arrival in this rather sprawling, pretentious house full of good and bad, the Duchess appeared at the end of a garden vista, in a crowd of yapping pug dogs. She sees to have suddenly aged, to have become a little old woman. Her figure and legs are as trim as ever, and she is as energetic as she always was, putting servants and things to rights. But Wallis had the sad, haunted eyes of the ill. In hospital they had found she had something wrong with her liver and that condition made her very depressed. When she got up to fetch something, she said, ‘Don’t look at me. I haven’t even had the coiffeur come out to do my hair,’ and her hair did appear somewhat straggly. This again gave her a rather pathetic look . . . . .

“We talked easily as only old friends do. Nothing much except health, mutual friends and the young generation was discussed. Then an even greater shock; amid the barking of the pugs, the Duke of Windsor, in a cedar-rose-coloured velvet golf suit, appeared. His walk with a stick makes him into a old man. He sat, legs spread, and talked and laughed with greater ease than I have ever known. At last, after all these years, he called me by my Christian name and treated me as one of his old ‘cronies.’ He has less and less of these, in fact it is difficult for him to find someone to play golf with. There were moments when the Prince of Wales’s charm came back, and what a charm it was! I noticed a sort of stutter, a hissing of the speech when he hesitated in mid-sentence. Wallis did not seem unduly worried about this and said, ‘Well, you see, we’re old! It’s awful how many years have gone by and one doesn’t have them back!'”

1971

Chanel is dead. One can no longer take for granted the feeling that she and her talent are always with us. She was unlike anything seen before. She was no beauty, but her appearance in the twenties and thirties was unimaginably attractive. She put all other women in the shade. Even in old age, ravaged and creased as she was, she still kept her line, and was able to put on the allure.

“She used to spend most of the time complaining in her rasping, dry voice. Everyone except her was at fault. But you were doing her a service by remaining in her presence, for even her most loyal friends had been forced to leave her. You tried to leave, too, for your next appointment, but she had perfected the technique of delaying you. Her flow of talk could not be interrupted. You rose from your seat and made backwards for the door. She followed. Her face ever closer to yours. Then you were out on the landing and down a few stairs. The rough voice still went on. Then you blew a kiss. She knew now that loneliness again faced her. She smiled goodbye. The mouth stretched in a grimace, but from a distance it worked the old magic.”