Bibliomania or Book Madness and the Gentlemen of Regency England

By Louisa Cornell

I will confess to a certain amount of obsessive behavior when it comes to books. Especially books written about or during the Regency era. My antique books are located in a bookcase next to a window. In case of fire, those precious volumes are coming out of the house quickly, one way or another. I have those stickers on my windows and doors that say “Firemen, please save my pets.” I have yet to find one that says “Firemen, please save my books.” However, I am still looking.

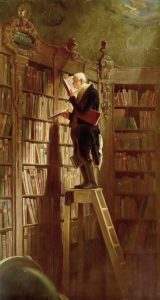

During the late 18th and at least the first half of the 19th century, book collecting became quite common among gentlemen, and some women, mostly in Britain and for the large part in the upper echelons of Society. As with all things, the lines between hobby, pursuit, and madness are easily crossed, more often than not blurred, and sometimes only separated by space and money. There are a number of reasons these people collected books. Allow me to introduce you to the most interesting ones. Bibliomania had many forms.

As powerful as my obsession is, it cannot hold a candle to the dark, at times frightening, pseudo-psychological madness that swept through the upper classes in Europe, and most especially England, in the nineteenth-century. At its height this strange madness was such that a number of satires were written on the subject – none of them flattering to the victims of this affliction, to be sure.

Gustave Flaubert’s Bibliomanie dramatized the legendary Spanish monk biblio-criminal who murdered a rival bookseller. Probably the most famous satire of this oddity was that of Thomas Frognall Dibdin, an English cleric, who in 1809 published his Bibliomania, or Book Madness : A Bibliographical Romance. In it, he goes so far as to ascribe actual symptoms to this disease.

He dramatizes a convincing pathology and uses medical language to describe the behaviors and idiosyncrasies of various sufferers of this malady. He presents as evidence rambling fictional dialogues based on conversations and real collectors he encountered. He categorizes those infected into classes based on the particular books they collected – First Editions, True Editions, Black Letter Editions, Large Paper Copies, Uncut Books (edges not sheared by binders’ tools,) Illustrated Copies, Unique Copies (those with specific bindings like morocco leather or specific linings like silk,) and Copies Printed on Vellum.

Dibdin’s work may have been fiction, but the characters in his book bear an uncanny resemblance to some of the better known book collectors of the time. In a particularly ironic twist, the book was very popular among book lovers and sparked reckless bidding wars over copies of it at auction. One particular copy started a 42-day auction at the 1817 Roxburghe sale. Most of the readers of Dibdin’s satire were from the upper class. To be certain they recognized many of their own in reading it. And why wouldn’t they? Dibdin was one of the founding members of the Roxburghe Club and a known bibliomaniac in his own right. Takes one to know one. Having read the book, I can say I recognize a few people I know today. Not mentioning any names for fear someone might mention mine. What happens at the Bibliomaniac Club or the House of Artie Collectors stays there.

As early as the 1730’s, there were those who purchased books as a symbol of wealth and power. Members of the socially elite and many who fancied themselves as scholars collected books, no matter the price, in order to build their own personal libraries. Where did you think all of those gorgeous libraries in stately homes came from? Once again, never underestimate the power of the mine-is-bigger-than-yours challenge, especially between men with ridiculous amounts of disposable income.

Beginning in 1804, English book collector Richard Heber (1773-1833) began to amass his collection of 146,000 rare books – books he stored in eight houses bursting at the seams. The cost of his impressive multi-house library? Over 100,000 pounds of his personal fortune.

Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872) sacrificed most of his fortune (250,000 pounds,) his living conditions, and his wife’s company to his ambition to own “one copy of every book,” in vellum manuscripts, no less. One of his contemporaries declared the man’s house a “dilapidated swamp of books.” His country home, Middle Hill in Worcestershire, had twenty rooms. Sixteen of the rooms were given over completely to books.

“The state of things is really inconceivable. Lady P is absent, and were I in her place, I would never return to so wretched an abode. Every room is filled with heaps of papers, books, charters, packages, and other things lying in heaps under your feet, piled upon tables, beds, chairs, and ladders.”

Still not convinced it was about power? He made it a point to outbid his most powerful rival, the British Museum, for entire lots of books at auctions. He accused his own son-in-law of being a “book thief” and had it written in his will no Catholic could look upon his book collection after his death. “Book thief” the son-in-law was Catholic. So strong was his attachment to his books, he wrote his will in such a way it took over 100 years of legal maneuvering to disperse his collection.

My Precious

After the French Revolution in 1799, French aristocrats emptied their library shelves and flooded British auction catalogues with French books before they fled France. Many of these collections arrived on the market as libraries were liquidated posthumously. However they arrived, the books brought staggering prices at auction. Prices of antiquarian texts preserved in the libraries of French nobles brought quadruple the price they had before the Revolution. Owning large sections of French books, especially rare and antique texts, added prestige and continental flair to an aristocrat’s library. Whether he read the books or not.

The 1812 auction of the library of John Ker, third Duke of Roxburghe, was an unforgettable moment in the history of book collecting. The flames of auction fever were fanned by both advertising and the wartime shortage of books. England’s wealthiest peers and even a representative of Napoleon attended the auction which lasted 47 days and included a large selection of books printed prior to 1500 – incunabula.

Dibdin wrote of the event as being full of “courage, slaughter, devastation, and phrensy.” Thomas de Quincy, author of Confessions of an English Opium Eater and a man well-acquainted with the throes of addiction, described the “literary addicts” he saw at this event as irrational and governed by “caprice” and “feelings” rather than reason. He called the method by which prices were determined pretium affectionus or “fancy price.” In his mind the book collector was nothing more than a dandy ruled by his emotions.

Michael Robinson in his upcoming book Ornamental Gentlemen : Literary Antiquarianism and Queerness in British Literature and Culture 1760-1890 speaks to an interesting side-note to the aristocratic book collecting phenomenon. Whilst Robinson concedes 1812 is too early to speak of a “gay” subculture, he does agree there was an “uncanny queerness of the stereotypical representation of the 19th century bibliophile.”

Translation?

Men who collected books were often seen as effeminate. Heaven forbid a young English lord be more interested in collecting and reading books than he was in riding to hounds, drinking, and wenching. As late as 1834, the British literary magazine the Athenaeum published an anonymous attack implying one of the prominent members of the Roxburghe Club was homosexual. Dibdin’s language, both in Bibliomania or Book Madness and in his epic Bibliographical Decameron, was replete with sexual double entendre and some phrases that can be seen as almost raunchy. Apparently men who wrote or enjoyed such language had to be homosexual. Who knew? Some of these people really would have done well to read the books in these libraries. Sexual innuendo was not unique to any portion of the population. Where do you think all of those heirs, spares, vicars, fourth, and fifth sons came from?

There were those aristocrats who collected books and built their libraries out of a serious love of the written word and a desire to preserve books not only for their own use, but for the use of scholars, their tenants, their neighbors, their children, and ultimately posterity.

Men such as Robert Harley, Earl of Oxford, who commissioned the creation of ballad collections like The Bagford Ballads and amassed large collections of Renaissance literature, Middle English literature, and Anglo-Saxon literature. His library and that of his son, Edward, was sold to the British museum in 1753 by the Countess of Oxford and her daughter, the Duchess of Portland.

Mark Masterman-Sykes of Sledmere House amassed one of the finest libraries in England and was considered both well-read and extremely knowledgeable in the areas of literature and art.

I’ll be discussing some of the more important stately home libraries of this era in a later post.

Until around 1814, when the mass printing of books became more practical and affordable, many saw the book collecting of aristocrats as denying their fellow countrymen a part of their literary heritage. The rich dilettante as conspicuous consumer of books he might never read was seen as having an antisocial disease that kept him from sharing his riches with the intellectual commoner. Perhaps.

However, whether they needed a serious intervention from the Hoarders crew, or were just too greedy for their pantaloons, or were in search of power and prestige – the Bibliomaniacs of the Georgian era saw to it many pieces of our literary heritage survived, stored up as the treasures they truly are. New ones are being discovered every day in the libraries and collections of National Trust houses and aristocratic stately homes all over the UK. But that is a story for another post.