From Tracy Grant:

A decade ago, on a research trip to London, I spent a wonderful morning at Apsley House, the Duke of Wellington’s London home, now the Wellington Museum, which stands at Hyde Park Corner. Along with taking in fascinating details, from the beautiful and surprisingly livable rooms, to the Waterloo memorabilia, to the naked statue of Napoleon Bonaparte at the base of the stairs, I learned about the banquets Wellington gave for Waterloo veterans on the anniversary of the battle. The idea of those banquets stayed with me through the years. Through writing the adventures of married spies Malcolm and Suzanne Rannoch at the Congress of Vienna, the battle of Waterloo, and post-Waterloo Paris (the latter of which two books, Imperial Scandal and The Paris Affair, include Wellington himself and several of his officers as characters), through the birth of my daughter (now four), through researching numerous other settings and bringing Malcolm and Suzanne and the series back to London.

Apsley House (English Heritage)

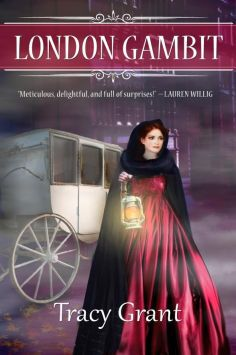

The timeline of the series naturally set the most recent book, London Gambit (which will be released tomorrow, May 5), in June 1818. Perhaps the date, three years after Waterloo, subconsciously influenced me, because as I developed the plot, I found echoes of the battle running through the story, both for the fictional characters – Malcolm and Suzanne, their friend Harry who was wounded at Waterloo, Harry’s wife Cordelia, their friends David and Simon who helped Suzanne and Cordelia nurse the wounded during the battle – and the real historical characters such as Fitzroy Somerset, Wellington’s military secretary, who lost his arm at Waterloo.

I needed a major social event for the denouement of the book, and I really wanted it to revolve round the anniversary of Waterloo on 18 June. But in 1818, Wellington was still British ambassador to France and based in Paris, though he already had come into possession of Apsley House. The house was designed by Robert Adam and built in the 1770s for the second Earl of Bathurst (who had been Baron Apsley before he succeeded to the earldom). Wellington’s brother Richard, Marquess Wellesley, purchased Apsley House in 1807 and engaged James Wyatt to improve it (with the assistance of Thomas Cundy). Though the grateful nation offered to build Wellington a London home, Wellington instead bought Apsley House from his brother in 1817 (to help Richard out of financial difficulties). In 1818 Wellington engaged Benjamin Dean Wyatt, James Wyatt’s son, to make repairs to the house. Wyatt installed the nude statue of Napoleon by Antonio Canova, which Wellington had acquired, at the base of the stairs.

Napoleon by Canova, in Apsley House (Victoria’s photo)

Though he purchased Apsley House in 1817, Wellington probably didn’t give his first banquet for Waterloo veterans at Apsley House until 1820, and the first of his banquets took place in a dining room that could only seat 35, so the guests were limited to senior officers. After the Waterloo Gallery was completed in 1830, up to 85 guests could attend, including guests who had not been present at the battle, but the guest list was limited to men. There’s a painting of the banquet in 1836 by William Salter (capturing the moment when Wellington proposed a toast to the sovereign, after which the band played the national anthem) that shows some ladies standing by the door, including Fitzroy Somerset’s wife Emily Harriet, who was Wellington’s niece, and a “Miss Somerset” who may be their daughter who was a baby at the time of Waterloo, born in Brussels in the weeks before the battle. Perhaps they had been dining separately in the house and joined the gentlemen for the toast.

Waterloo Banquet by William Salter, 1836

While I worked on the first draft of London Gambit, I danced round what to do with the Waterloo anniversary. I thought about having a fictional character give a dinner on 18 June. I even thought about having Wellington come over from Paris for the fictional dinner. And then I thought—Wellington did own Apsley House in 1818. He could have given a dinner on the anniversary of Waterloo (even if in fact he did not). And, since the dinner in my book would be fictional, he could include women among the guests…

Historical novelists always to a certain degree combine fact and fiction because we fill in gaps in the historical record. This is even more true when one writes novels such as I do with fictional main characters and real historical figures in major supporting roles. One inevitably combines historical events with fictional ones. I try to stick closely to the historical record, but of course I end up taking some liberties with it whether it’s Lady Caroline Lamb, a childhood friend of my fictional Cordelia Davenport, putting Lord and Lady Castlereagh at a fictional ball they of course wouldn’t have attended, having Malcolm pressed not delivering messages for Wellington during Waterloo (though in point of fact with so many of his aides-de-camp wounded, Wellington did press some civilians into service), or having Castlereagh, Wellington, and Sir Charles Stuart preoccupied with the intrigue surrounding the death of my fictional Antoine Rivère in post-Waterloo Paris. I try to stick to having real historical characters only do things they

might have done. For instance, if a real histori

cal figure was known to have a string of love affairs, I might involved them in a fictional one, but if they were known to be a famously faithful spouse, I wouldn’t think it was fair to do so.

By that logic, since Wellington could have come to London and given a dinner on the third anniversary of Waterloo, having him host a dinner in the book was in line with the sort of historical liberties I take in the series. Fitzroy Somerset was Wellington’s secretary at the British embassy in Paris in June 1818, but he stood for and won a parliamentary seat at Truro in the General Election in 1818, and he was in Truro for the election, so I had already decided it was all right to have him visiting England in June so he could be a character in the book. I debated some more about the banquet, wrote the ending with Wellington giving the dinner at Apsley House, debated changing it in subsequent drafts. In the end I left it, with an historical note explaining the liberties I had taken. Reading over the galleys, I was glad I did. The Waterloo anniversary ties the themes in the book together beautifully and having the event at Apsley House with Wellington present gives the added resonance to the echoes of Waterloo that run through the story.

Author Tracy Grant with her daughter and their kitties

For more information about Apsley House and Wellington, the Victoria and Albert Museum offers an excellent publication book Apsley House: Wellington Museum(London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2001). The Apsley House website is here.

Readers, how do you feel about writers taking liberties with the historical record? Writers, what liberties have you taken with historical figures, events, and timing?

This was a fascinating article about Apsley House but also has great insight into Tracy's style of writing. The type of liberties she takes are exactly as they should be – as she says, "filling in the gaps". Nothing is worse that a writer who recreates history to suit the story. I love that Tracy builds around the known but only invents where there is an unknown. Very few historical fiction writers can claim that ability.

Such a treat to be a guest on this great site! Thank you, Kristine and Vicky!

I don't mind authors making slight changes to historical events, as long as they take the approach which Tracy does i.e. not to make any real person act out of character, and to include a Note identifying and explaining any changes.

I read London Gambit as soon as it came out, after re-reading several of the earlier books and novellas. It's one of may favourite series, and Tracy Grant does a superb job of combining history with fiction.