AND HERE IS POLESDEN LACEY, A STATELY HOME IN SURREY WITH A BEAUTIFUL VIEW AND A CONNECTION TO REGENCY PLAYWRIGHT AND POLITICIAN RICHARD BRINSLEY SHERIDAN…

Polesden Lacey, the Edwardian country estate on a spectacular natural site overlooking a deep valley in Great Bookham, near Dorking, in Surrey, is best known for its influential hostess-with-the-mostest, Mrs Ronald Greville (aka “Mrs Ronnie”), who was an intimate of the royal family and anyone else who could claim to be anyone at the turn of the 20thcentury.

But it actually has a very long history dating back to Roman times – and, indeed, would it not have been a perfect site for a Roman temple? – though documentation of buildings on that site date back only to the 14thcentury or thereabouts.

One of Oliver Cromwell’s roundhead officers – the Parliamentarians who fought against the Cavalier forces of King Charles I in the English Civil War – bought this divine property in 1630, keeping the existing farm and constructing a new residence in situ.

The Regency-era playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan – after a long line of other owners and leaseholders – came into the picture in 1797, when his trustees, one Lord Grey and a Mr Whitbread, bought the Polesden Lacey lease for 12,384 pounds, using the 8,000 pound dowry of Sheridan’s second wife, Hester Jane Ogle, and money raised from the sale of shares in the Drury Lane Theatre, which he owned. (another source stated a higher price of 20,000 pounds was paid.)

The Rivals and The School for Scandal are Sheridan’s best-known plays, still widely performed today. In my opinion, the world lost a literate and witty wordsmith when Sheridan decided to enter the world of Whig politics, but there was perhaps another motive to his service in parliament. As an MP he was safe against arrest for debt, and the playwright was chronically in debt. When he lost his seat in 1812 his creditors showed up in droves to claim what was owed them. Hence the loss of Polesden Lacey after a leasehold that spanned almost twenty years.

The breathtakingly beautiful Elizabeth Lynley, from the painting by Thomas Gainsborough. Elizabeth was from a very well-known family of musicians in Bath with whom the painter was extremely friendly;

he painted many family members.

This sympathetic piece in the theatrehistory.com website sums him up:

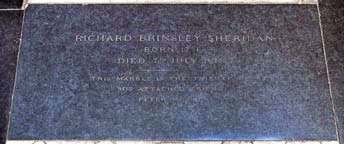

“The real sheridan was not a pattern of decorous respectabilty, but we may fairly believe that he was very far from being the Sheridan of vulgar legend. Against stories about his reckless management of his affairs we must set the broad facts that he had no source of income but the Drury Lane Theatre, that he bore from it for thirty years all the expenses of a fashionable life, and the theatre was twice rebuilt during his proprietorship, the first time (1791) on account of its having been pronounced unsafe, and the second (1809) after a disastrous fire. Enough was lost in this way to account ten times over for all his debts. The records of his wild bets in the betting book of Brooks’ Club date from the years after the loss, in1792, of his first wife [the incomparable beauty Elizabeth Lynley] … the reminiscences of his son’s tutor, Mr Smyth, show anxious and fidgetty [sic] family habits curiously at variance with the accepted tradition of his imperturbable recklessness. He died on the 7thof July 1816, and was buried with great pomp in Westminster Abbey.”

If you are so inclined, you can pay Sheridan a visit in the Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey the next time you are in London:

Although Sheridan began to demolish parts of the house around 1814, he did not get very far owing to burgeoning ill health and those always-problematic finances. He is credited, however, with extending the charming Long Walk to 1,300 feet from 900 feet. This walk was first laid out along the valley in 1761 on the 1,400 acre estate and it remains a very popular hiking trail with national trust visitors from far and wide as well as with local families and walking groups. Parallel to the Long Walk is another, called the Nun’s Walk, which is lined with beech, yew, and holly trees. (And, yes, for those of you who like to know these things, there is even a ha-ha, below a yew hedge that marks the garden’s boundary.)

Sheridan also made some attempts at landscaping the Polesden Lacey garden. In respect to that garden – and to his legendary reputation as a ladies’ man – the National Trust booklet attributes this quote to him: “Won’t you come into the garden? I would like my roses to see you.” Sheridan to a beautiful female guest at Polesden Lacey

The text in that booklet emphasizes how much Sheridan loved his country home, which he called “the nicest place, within a prudent distance of town, in England.” Notwithstanding his creditors, and the dual responsibilities of managing the Drury Lane Theatre and his parliamentary duties, he surely relished his role of country landlord and entertained, as they say, lavishly.

This “portrait of a gentleman”, by John Hoppner, has been traditionally

identified as that of Richard Brinsley Sheridan

But, alas, the property was sold again, to a Joseph Bonsor (1768-1835), who commissioned the period’s master builder, Thomas Cubitt, to design and erect a new house, and this redesign formed the nexus of the current stately home. According to Bonsor’s obituary in The Gentleman’s Magazine, he was a self-made man, “the founder of his own fortune.” His success in the wholesale stationery trade enabled him to secure the sale of Polesden Lacey from Sheridan’s son in 1818.

Thomas Cubitt rebuilt the house in the neo-classical style. On the south front of the house, part of Cubitt’s villa is still visible: six bay windows with an Ionic-columned portico.

Some repairs taking place recently on the neo-classical south front of Polesden Lacey

(what you don’t see is the graffiti chalked by schoolchildren on the steps leading to the great lawn)

The next owner in line was a prominent Scottish physician (and, yes, a Scots theme runs through this history) named Sir Walter Farquahar. It was this good doctor who extended the walled garden and put more order into the various plantings. But more was to come for this splendid parcel of land.

In 1902 the estate became the property of Sir Clinton Dawkins, who commissioned the architect Sir Ambrose Macdonald Poynter, a major London architect whose grandfather was also an architect (a co-founder of the Institute of British Architects whose father was a distinguished painter) to make extensive renovations to Polesden Lacey. He went on to build the Royal Over-Seas League, Park Place, St James’s, a few years later.

And then, in 1906, along came the redoubtable Mrs Greville… who employed the architectural firm of Mewes and Davis (the designers of the Ritz Hotel in London) and the interior decorating firm of white, Allom & Co., to further gild the lily this house was becoming. (See below for the changes and expansions from the 1903 house to the present-day.)

This gives an even better idea of the expansion!

Some family background… Margaret Helen Anderson was born out of wedlock in 1863 to a Scottish brewery multimillionaire named William Mc Ewan and a woman named Helen Anderson. Mrs Anderson was said to be married to – or lived with – a man named William Anderson, who was a porter employed in Mc Ewan’s brewery. Mrs Anderson and Mr Mc Ewan wed after the death of Mr Anderson in1885. On Mc Ewan’s death in 1913, Margaret inherited his entire estate, becoming one of the wealthiest women in Britain.

This gorgeous portrait (above) painted in 1891 by Carolus-Duran (who was John Singer Sargent’s teacher) sits on the landing of the central hall, on the way to the dining room… exactly where MrsGgreville loved to make a dramatic entrance and meet her guests as they went in to dinner…

Margaret had been married in 1891 to the Honorable Ronald Henry Fulke Greville, a handsome gentleman identified as “a member of the racy Marlborough House set” who was said to have been “witty and good-natured.” Photos show him with a rakish moustache and piercing light blue eyes. He was the eldest son of the 2nd Lord Greville and a conservative MP for Bradford as well as a Captain in the 1st Life Guards. Greville and Margaret were, by all accounts, happily wed for seventeen years, until he died suddenly from complications of an emergency operation. She never remarried, though, as an immensely wealthy widow she probably had a number of men desirous of being in her company.

Why is this National Trust property, Polesden Lacey, important?

Well, for one, it is so closely associated with events in British history and with prominent historic personages – like Sheridan, like the assorted royals and foreign visitors with whom the Grevilles interacted – and Mrs Greville herself was an amazing character whose talent lay in bringing people together in an intimate salon setting and who was said to have had a remarkably sharp and witty tongue.

We would, I think, like to know much more about what she thought about what and whom, living through those two horrific world wars that upended British society as she had known it, but, as all of her personal letters, diaries and other papers were destroyed after her death, at her request…

One can b

e sure. then that the many things that swirled about her, all the racy and intriguing political/private/scandalous goings-on/et al., of the Edwardian era and the reign of King George VI (father to the present Queen, Elizabeth II) will never see her viewpoint’s light of day. It was too bad, because as an intimate of so many well-connected and powerful people, she was in a position to hear and see a great many things that could be illuminating, even obliquely.

e sure. then that the many things that swirled about her, all the racy and intriguing political/private/scandalous goings-on/et al., of the Edwardian era and the reign of King George VI (father to the present Queen, Elizabeth II) will never see her viewpoint’s light of day. It was too bad, because as an intimate of so many well-connected and powerful people, she was in a position to hear and see a great many things that could be illuminating, even obliquely.

She was, for one, very close to Elizabeth, the Queen Mother – Elizabeth and George VII (before he became king) spent part of their honeymoon at Polesden Lacey — and Mrs Greville left the Queen Mother and her daughters the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, her most precious jewels…one a diamond necklace purported to have been owned by the French Queen Marie Antoinette.

The widely-held expectation, in fact, was that she was going to leave Polesden Lacey to the House of Windsor in her will. (She and Ronald had no children.) However, she did not do that, gifting it to the National Trust instead.

(For those who want to know and see a little more than can be covered in this piece, there is an extensively-illustrated biography, published by the National Trust in 2013, written by Sian Evans: Mrs Ronnie: The Society Hostess Who Collected Kings.)

The Paterson Children, by Sir Henry Raeburn

One of the outstanding collections amongst the many exquisite and valuable collections at Polesden Lacey that I must mention hearkens back to that Scottish connection I mentioned previously, and those are the remarkable paintings in the dining room, many of them by the Scottish portraitists Sir Henry Raeburn (a favorite of King George IV), Allan Ramsay (a favorite of King George III), and by other Scots of lesser renown.

So, again, what is so special about Polesden Lacey?

Along with the above glorious paintings (and the fabulous collections of miniature paintings, ceramics, etc., and Polesden Lacey’s place in history and association with historical personages, it is also (and this is not such a minor thing), as the National Trust describes it:

“an English estate in the traditional manner – a blend of open lawns and enclosed rose gardens, mature native trees and exotic species from overseas, formal terraces and informal shrubs…. An appealing yet practical complete landscape.”

And this is very true:

“the estate was bought by successive owners because it was beautiful… but…its maintenance was only possible because of Mrs Greville’s considerable personal fortune.”

We must not forget that we visitors (including this child from London pictured below and the many families lounging on deck chairs in the background and those walking all the beautiful trails) are much the richer for it, as its maintenance – keeping it beautiful – was possible only because of Mrs Ronnie’s considerable personal fortune and her concern for future generations. It’s in trust for everyone in Britain and all should be very grateful it passed on to the people of Britain and not to the royal family of Windsor.

Jo Manning

Polesden lacey

April 2015

Click here to read a 2012 Daily Mail article about the brouhaha surrounding pheasant shooting rights on the Estate.