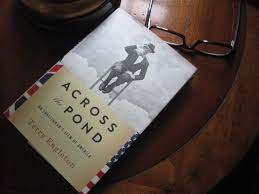

In Across The Pond: An Englishman’s View of America, author and literary critic Terry Eagleton skewers Americans relentlessly – but it’s okay, because Eagleton gets around to other nationalities, as well. Especially his own (British, as the title of the book implies). Eagleton sets a wry tone in his introduction, where he writes, ” . . . the discerning reader will note that when I make large generalizations about the British, Irish and Americans in this book, my comments must occasionally be seen as involving a degree of poetic license and a pinch of salt.” From there we embark on a tour de force of political incorrectness that’s by turns either oddly refreshing or startlingly at odds with what one personally knows to be true.

Eagleton compares the Americans to the British early on while setting forth one cause for the divide in our national characters: “Henry James thought that America lacked mystery and secrecy, that its landscapes were all foreground, but found just such an air of enigma in Europe. This was not, he considered, by any means wholly to its credit. Civilisations which prize the mannered, devious, playful and oblique generally have aristocratic roots, since it is hard to be mannered, devious and playful while you are drilling a coal seam or dry-cleaning a jacket. And aristocratic social orders, as James was to discover, can be full of suavely concealed brutality. A dash of American directness would do them no harm at all. A culture of irony requires a certain degree of leisure. You need to be privileged enough not to have any pressing need for the plain truth. Facts can be left to factory owners.” Of course, this example supposes that British aristocrats make up the whole of the English population. Or at least that part of it which is playful and/or enigmatic. And surely the UK has at least one or two plain talking dry cleaners available to them in a crisis?

In an attempt to rationalize American zeal, willingness and industry, the author writes, “It was a communal act of willing that brought America about in the first place. The nation itself is the work of the will. It is not just a country like any other but a project, a vocation, a mission, a destiny, a spiritual enterprise. Nobody thinks this about Belgium. It is not the case with Wales, Slovenia or the United Arab Emirates, which some Americans might suspect is a movie company. Britain is not the work of the will. The British never planned their empire, for example. It just fell into their laps in a fit of absent-mindedness. They awoke one morning to find that they were governing India, even though nothing had been further from their thoughts. They did not particularly savour the prospect, but it seemed churlish not to get on with it.” One can just about hear the Wellesley’s turning over in the respective graves now.

As Eagleton warned in his introduction, much salt was pinched in the writing of this book and oddly enough, the majority of it falls on the British Isles, rather than on America, as the title would suggest. “Like comedy, the British are traditionally suspicious of the success ethic. Unlike Americans, they are not an affirmative nation. Among their national icons are a ship that sank (the Titanic) and a calamitous military defeat (Dunkirk). Defeat is what the British are particularly good at. They are maestros of utter disaster. No doubt there are bunkers deep below Whitehall where intensive seminars in how to screw up are secretly conducted. Glorious defeats, like the Charge of the Light Brigade, are almost to be elevated over stupendous victories. The British are not particularly heroic, but brave out of necessity. Unlike Americans, the only kind of heroism for which they have a sneaking admiration is one forced on you when the odds are hopeless and your back is to the wall. After such sporadic bursts of self-sacrificial glory, they resume their normal, grumpy, unheroic existence until the next catastrophe happens along. They need the occasional hardship in order to show what stuff they are made of, and suspect that American civilization is too easy and flaccid in that respect. The States may be full of virile, chisel-jawed, bestubbled types, but all those stretch limos and Jacuzzis are fatally weakening. This is ironic, since quite a few Americans see the British themselves as effete. This is largely because their accents can sound vaguely gay, rather like their prose styles.”

Wellington continues to roll, Churchill’s moaning aloud and I’m left wondering exactly what England ever did to Eagleton to deserve such treatment. Perhaps Across the Pond would have been funnier if it had been based on truths. Even stereotypical truths. Like this one:

“An American friend of mine once confessed to me that he found a certain philosopher rather standoffish. I told him that he had the word almost correct: it wasn’t standoffish, it was Scottish. Scottish men tend to smile less than American men do, a fact that can easily be mistaken for churlishness. In fact, a male Scot will probably smile only faintly if he meets you after a twenty-year absence and you are his mother.”

Now, that’s funny.