Nunhead Cemetery in Southwark is perhaps the least known, but the most attractive, of the seven Victorian cemeteries on the outskirts of London. It’s formal avenues of towering lime trees and original Victorian planting gives it a truly Gothic feel. Its history, architecture and stunning views make it a fascinating and beautiful place to visit. While much of the cemetery is mysterious and overgrown, many of its features have recently been restored to their former glory. This is thanks to funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and Southwark Council.

There is a tour conducted by the Friends of the cemetery, open to all, on the last Sunday of each month, starting from the Linden Grove gates at 2:15 p.m. and the two-hour guided tour of a romantic and overgrown Victorian cemetery features 1,000 ivy-clad angels and mighty Victorians buried in the green heart of Peckham. Consecrated in 1840, Nunhead contains examples of the magnificent monuments erected in memory of the most eminent citizens of the day, which contrast sharply with the small, simple headstones marking common, or public, burials. It’s formal avenue of towering limes and the Gothic gloom of the original Victorian planting gives way to paths which recall the country lanes of a bygone era.

The following account of Nunhead Cemetery appeared in a volume titled, Old Humphrey’s Walks in London and its Neighbourhood (1845) –

This Nunhead Cemetery of All Saints, occupies a commanding site between Peckham and the Kent road, sloping down to the east, north, and south-west, at a distance of some three or four miles from London, and, though far from being completed, gives a fair promise of equaling those which have already won the public approbation. It is the largest of all the cemeteries, comprising at least fifty acres.

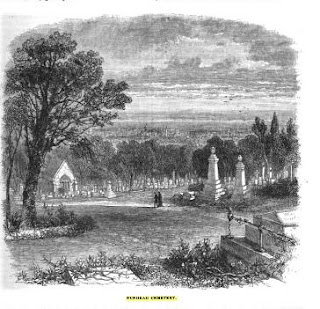

In walking to this place I observed, on a neighbouring hill, a singular-looking erection, and the gravedigger, who is even now, with an assistant, preparing a “narrow house” for an inanimate tenant, tells me it is a telegraph. . . . There is a glorious view of London from this spot. The five oaks stretching themselves across the cemetery are strikingly attractive; and when the church is erected on the brow of the hill yonder, it will be a goodly spectacle. The palisades of the boundary, mounting tier above tier; the fine swell of the ground and commanding slope; the groups of young trees, and flowers of all hues, are very imposing. In a few fleeting years the cemetery will be, indeed, an interesting spectacle.

I have walked round the spacious enclosure. What an extended space for a grave-ground ! What a goodly homestead for the king of terrors! Here seems to be room enough to bury us all! At present the monuments are but few; but this is a want that mortality will soon supply. Fever, and consumption, and death, and time, are industriously at work. It is not to one, but to all, that the voice of the Eternal has gone forth: ” Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return,” Gen iii. 19.

And in The Sunday At Home, Voume 25 (1878), we read:

MANY “parks” in the suburbs of London are now treeless, or planted only, in front “gardens,” with shrub-like trees. A visitor of Nnnhead Cemetery, however, unacquainted with its history, must feel inclined to say, “Here is a picturesquely wooded and undulating Surrey park, in which double rows of houses have not supplanted shady avenues; the turf and trees, over and under which a favoured few once wandered, have been turned into a receptacle and a canopy for thousands of the dead, who, whatever was their station in life, are like the dead slave in the Greek Anthology, all now “equal to Darius.'”

Nevertheless, some forty years ago, the cemetery was simply fifty acres of field and meadow. All the tasteful planting has been done by the cemetery company, and it is rare as well as rich, including shrubs which prove that landscape-gardening here is made a speciality, and that no expense is spared upon it. Within the cemetery, there is an ably superintended, strongly-manned nursery, which keeps the flower-beds bright, and the graves also, after the old Welsh custom. It is curious to think of little coffin-shaped parterres, bordered with whitewashed stones, and planted with old-fashioned flowers, far away in the quiet hollows of the Welsh hills—most of the graves with no other memorial than the piously-tended flowers, when on a summer day we see the blaze of blossom at the foot of gleaming marble and glittering granite in Nunhead. But it is winter at the time of our pleasant wanderings there. Some of the graves are still bright with flowers, but glossy shrubs are their chief adornment. Throughout the place, however, laurustinus blossoms freely, although chrysanthemums hang wilted heads, and rowan trees and holly and rose bushes are red with equally seasonable berries. In spite of gardener’s care, and the mildness of the season, there is nevertheless, an unmistakable look of winter in the place. Trees and bushes are leafless; dark, dank dead leaves lie trodden, or waiting to be trodden, into the fat clay; jungles of leafless sprays bend under sugared-almond-like ovals.

Although, since the Bishop of Winchester consecrated the forty-acre All Saints portion of the ground in 1840, some 45,000 persons have been buried in that portion, and the unconsecrated divided from it by no invidious boundary,—there are solitudes still in Nunhead cemetery; graveless, or only dotted with single tombstones, white, grey, black or green. Moss-grown red paths wind into nooks that seem, so far as either dead or living are concerned, as far from London as if thoy were in the Fiji Islands, until we hear the rumble and panting of one of the trains that frequently rush around. The roar of London is audible in Nunhead; the drab masonry of South London, redeemed from meanness only by its smokily, mistily, mysterious mass, spreads almost to the gates, but on other sides you see green swelling country, houseless, or only marred by straggling lines of brick and mortar.

The first grave in Nunhead was dug in October 1840. The average number of burials in it, during the last ten years, has been 1685 per annum, 1350 in the consecrated, and 335 in the unconsecrated ground. The total of burials having been more than four myriads, it is almost startling to hear the number of the “square” in which any one of the slightest notability or notoriety lies, given without a second’s hesitation by the superintendent. Before singling out graves of any kind o

f note, let us ramble round the cemetery.

The birds are not singing, but their half sad little chirpings and twitterings seem more in harmony with a burial ground than full sung, especially on a day like this, when a winter sun is vainly trying to shine through brown-holland-like clouds. The sheen of the silver birches’ bark seems self-evolved in the sombre midday dusk; willows and ashes “weep” still over green stones, on whose graves they have already shed their leaves.

Nunhead Cemetery is open daily, 8am-4pm in winter.

You can read a poem entitled Nunhead Cemetery by Charlotte Mew here and watch a video of the cemetery here.

Thank you for this…very interesting! I am planning a visit in early May to Kensal Green, another great London cemetary

You can learn a great deal about the people of an era by studying their funeral rituals and their manner of memorializing the dead. I spent many hours in the cemetery around the 11th century Church of St. Mary and St. Peter in Kelsale. And I have visited the cemeteries in New Orleans and Savannah. One often wonders if we create these ornate cities of the dead to keep our loved ones with us in those avenues of stone angels.