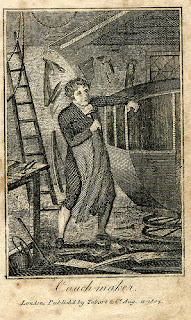

Charles Dickens gives us details of the process is All the Year Round:

The coachmaker’s wood-loft contains oak, ash, and elm, from trees which have lain a year after falling, and which, after I.-mis; cut into planks of various thicknesses, must remain unused as many years as they are inches thick. A certain class of carriage-builders use green wood of any quality, relying on paint to cover all defects, not expecting or caring to see any customer twice. There are some advertising fabricators of diminutive Broughams who are especially to be avoided.

Besides European woods, there is also a large demand for mahogany and knee-wood from the Gulf of Mexico, Quebec pine, birch and ash from. Canada, tulip-wood and hickory from the United States. These, for the most part, are cut ready for use by steam saws before going into the hands of the coachbuilder.

The first step for the construction of, say a Brougham, is to make a chalk drawing on a brick wall, of the same size. On this design depends the style of the carriage. Some builders are happy or unhappy in designing novelties; others have a traditional design, a certain characteristic outline, from which they will on no consideration depart. The next step is to make patterns of the various parts. In first-class factories, each skilled workman has been apprenticed to, and follows only one branch of, the trade. The leading workmen in wood are body-makers, carriagebuilders, wheelers, and joiners—all highly skilled artisans, as may be judged from the fact that a chest of their tools is worth as much as thirty pounds.

The framework is sawn out of English oak. The pieces, when cut by the band-saws, are worked up, rabbeted, and grooved to receive the panels, and thus a skeleton is raised ready for the smith and fitter, who, taking mild steel or homogenous iron, forge and fit a stiff plate along the inside cart-bottom framework, following the various curves, and bolted on so as to form a sort of backbone to the carriage, which, takes the place of the perch:—universally the foundation of four-wheeled carriages before the general adoption of iron and steel.

The frame is then covered with thin panels of mahogany, blocked, canvased, and the whole rounded off. After a few coats of priming, the upper part is covered with the skin of an ox, pulled over wet. This tightens itself in drying, and makes the whole construction as taut as a drum-head, the joints impervious to rain, and unaffected by the extremes of heat or cold. Meanwhile the “carriage-maker,” the technical name of the artisan who makes the underworks, arranges the parts to which the springs and axles are bolted, so that the body may hang square and turn evenly with the horses, on the fore-carriage. The coachsmith and spring-maker have also been at work arranging the springs, the length and strength of which must be nicely calculated to the weight estimated to be carried. The ends of these springs are filled with india-rubber, to make the carriage run lightly and softly.

|

| McNaught and Co., Worcester |

Though from a much earlier date, Samuel Pepys records a visit to his coachmaker in his Diary: “I to my coachmaker’s, and there vexed to see nothing yet done to my coach, at three in the afternoon; but I set it in doing, and stood by till eight at night, and saw the painter varnish it, which is pretty to see how every doing it over do make it more and more yellow: and it dries as fast in the sun as it can be laid on almost; and most coaches are, now-a-days, done so, and it is very pretty when laid on well, and not too pale, as some are, even to show the silver. Here I did make the workmen drink, and saw my coach cleaned and oiled; and staying among poor people there in the alley, did hear them call their fat child Punch, which pleased me mightily, that word being become a word of common use for all that is thick and short. At night home, and there find my wife hath been making herself clean against tomorrow; and late as it was, I did send my coachman and horses to fetch home the coach to-night, and so we to supper, myself most weary with walking and standing so much, to see all things fine against to-morrow, and so to bed.”

|

| The Coachmaker Pub 88 Marylebone Lane, London |

And in closing, Dear Reader, you will not be too surprised to find that, yet again, the fates have brought us to another encounter with the Duke of Wellington with this passage from All the Year Round – “So recently as 1837 a . . . scientific book on pleasure carriages was published by Mr. Adams, then a coachbuilder, since a distinguished mechanical engineer, and he gives no hint of the coming carriage reform. Mr. Adams made an early display of his ingenuity by building a carriage now only remembered in connexion with the great Duke of Wellington, who drove one to the last, the Equirotal, which, in theory, combined the advantage of a two-wheeled and a four-wheeled carriage, the forepart and wheels being connected with the hind body by a hinge or joint, so that no matter how the horses turned, the driver always had them square before him; a great advantage. It was also, at the cost of something under five hundred pounds, convertible into a series of vehicles. Complete, it was a landau, holding four inside, besides the servants’ hind dickey; disunited, it formed at will a Stanhope gig, a cabriolet, or a curricle. In spite of the example of the Iron Duke, and the eloquent explanations of the inventor, the public, either not caring for such a combination, or not willing to pay the price, never took to the Equirotal.”

|

| The Duke of Wellington’s Equirotal carriage pictured lower left |