Postman’s Park today, showing the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice

aka The Wall of Heroes under the thatched awning.

I first heard about Postman’s Park from my friend and colleague Hester Davenport, the biographer of Fanny Burney and Mary Robinson. She suggested it as someplace different and educational to take my London grandchildren. And, different, it truly is.

This tiny park, a blot of fastidiously landscaped green, elevated above the surrounding streets and tucked out of the way behind high buildings, is named for the site of the former General Post Office. Though only a few streets from St. Paul’s Cathedral, getting there is not so easily accomplished; it behooves one to refer to a map.

Starting at St. Paul’s, orient yourselves with this map showing the cross streets…

As can be seen from this map, it was the site of several former burial grounds connected to a number of churches. In 1898, however, this quiet spot was incorporated as a park, becoming a place for “postmen,” i.e., postal office employees, to take breaks and to eat their lunches.

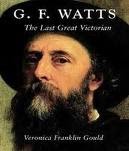

In 1900, the painter George Frederic Watts selected the location to become a memorial to the altruistic among us, the ordinary, average people who died giving their lives for others. He would name this the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice, or the Wall of Heroes. These heroes were individuals who would otherwise never have been remembered, their deaths never commemorated; they were ordinary people, not famous. Watts was a celebrated artist of the Victorian period, a painter, portraitist, and sculptor often called the last great Victorian artist. In fact, the most recent biography of Watts, by Veronica Franklin Gould (who’s also working on a biography of his second wife Mary Seton Watts), has this very same title.

The cover painting is from a self-portrait…

Over and above his artistic talent – often described as “titanic” — he was an active and zealous advocate of social change who believed art could promote such change and make life better for all. From a working class family himself, he was interested in the elevation and recognition of the often-unheralded common man.

Another view of the Wall of Heroes

To celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria, he wrote a letter in 1887 to The Times proposing “to record the names of these likely to be forgotten heroes.” He felt it would “make London richer by a work that is beautiful, and our nation richer by a record that is infinitely honourable.” He concluded, “The material prosperity of a nation is not an abiding possession; the deeds of its people are.”

A place for quiet contemplation at the end of the day…

Watts was serious and persistent in pursuing his concept of recording the stories of heroes in everyday life. He envisioned a kind of covered walkway against a marble wall that would be inscribed with the names of these people. His first idea was to build it in Hyde Park, but that didn’t work out. He began to spend a great deal of his time – and even considered selling his homes and other properties– to finance this project.

This says it all…in Watts’s own words and those of the Apostle John…put up by his widow…

One of the first: the brave young girl Alice Ayres’s memorial tablet, designed by William De Morgan and installed in 1902.

Postman’s Park in the City of London area known as Little Britain became home to Watts’s concept. He visualized and began to design a wall that would be set with ornate ceramic tablets dedicated to the memory of men, women, and children who’d given their lives for others. It evolved into kind of a loggia overhung with a thatched awning; 120 memorial tablets would be set into this protected wall. The tiles were commissioned from the prominent and renowned ceramicist William De Morgan.

This shows the arrangement of the older and newer tiles set together on the Wall…

Although it could easily be interpreted as yet another example of cloying and excessive Victorian sentimentality, the Memorial works because it is so much more than mere sentimentality. It is a very real and moving place. Who among us could remain unmoved whilst reading these solemn tiles?

Sadly unable to save himself…Leigh Pitt’s memorial is the latest to be added. You can read a full article on the service

here.

This wall of tiles certainly moved my grandchildren, one of whom – the eldest — walked it once, carefully reading the memorial tiles, and then walked it again, paying even closer attention to the text. Another grandchild, though, chastised me, saying it was too sad, and why had I taken them there? The stories of these deeds made her cry. Well, they made me cry, too.

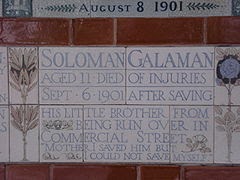

Aged just 12, he could not abandon his drowning friend…

They are really heartbreaking. The plight of these Victorian children and young adults, for most of them are very young… Trampled by horses, drowned, burned to death…not pretty. But that there are those who would put their lives at great risk to attempt to save others…well, that was…heartwarming…though immeasurably, heartbreakingly sad.

Trying to save a child from a runaway horse, she died of injuries received…

It does give one faith, does it not, in the goodness of others, to know that there are those individuals who give not a thought for themselves when the lives of others are at risk? In this country, in the last century, I am reminded of the 9/11 first responders, many of whom died (or have suffered life-threatening illnesses) in their selfless efforts to save their fellow man. It is extremely touching, this notion of self-sacrifice. How many of us would do this?

A Stranger AND A Foreigner! This one made us pause…what a statement!

When the park was opened, only four of the projected 120 tiles in place; a further nine were added during G.F. Watts’s lifetime. Mary Seton Watts oversaw the installation of thirty-five more tablets after Watts’s death in 1904, but as the building of the Watts Gallery and Chapel in Compton began to take more and more of her time, she lost interest in managing the project. (It was further complicated by a falling-out with the new tile manufacturer she’d engaged.)

A mere five more tiles were added during her lifetime – she died in 1938 – and the last tile in seventy-eight years was only added in 2009, by the Diocese of London. (See the end of this article for more about the Watts Gallery.)

Another drowning…

After this sobering look at Victorian self-sacrifice, we celebrated death with a greater appreciation for life. My grand-daughter Zoe jumped at least 2 ½ feet over a stone tablet; we all ate –and enjoyed — ice cream cones. Life, thank goodness, goes on and children play.

My exuberant grand-daughter letting off some steam after going through the Wall twice…

Here we are walking through Postman’s Park eating ice cream cones; the overcast day threatened rain, quite in keeping with the subdued nature of this unusual site…

George Frederic Watts died in 1904, not having fully realized his dream of the wall in Postman’s Park. There were spaces for more tiles, but he was now into his late 80s, not at all well, and it had become more expensive to carry on the work. Though he’d maintained a file of unused clippings on other individuals whom he felt deserved a place on the wall, when he passed away at the age of 87, leaving his widow in charge, the impetus to continue the project faded away.

I saved him but I could not save myself…

It’s remarkable, however, that we have what we do have at Postman’s Park. It’s a lasting legacy to a great man who wanted to celebrate the goodness of the common man, woman, and child in a beautiful and unforgettable way. The Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice was Grade II listed in 1972, to better preserve it for posterity.

George Frederic Watts, Victorian artist, social philosopher, at work…

Those of you who are particularly astute might recognize some scenes from a movie of a few years back, Closer, based on a play by Patrick Marber, which take place in Postman’s Park. Key scenes between two of the characters – played by Natalie Portman and Jude Law — took place here, generating a new interest in the site as a result. The full name of the enigmatic Natalie Portman character, the young stripper Alice — Anna Friel had the role in the stage production – was, by the way, Alice Ayres. Alice the stripper took her name from the tile in the park, the name of the brave girl who lost her life saving three children from a burning building.

Before the play and the film, most Londoners had never heard of Postman’s Park. But, the day we were there, it was fairly well populated by people sitting on the benches who appeared to be locals, and two tour groups came by, one group on bikes who hailed from Denmark. The word has obviously gotten around!

Portrait of Mary Seton Watts by her husband George Frederic Watts; she was his second wife. His first wife was the actress Ellen Terry, who was married to him for only one year when she was 16 and he was 47. (The marriage was dissolved.) Mary Watts, who married G.F. when he was 69 and she was 36, outlived him by 34 years…

First wife Ellen Terry… G.F. Watts’s portrait of her is named Choosing…

Although a bit off the beaten path for tourists and locals, Postman’s Park is well worth a visit, as are the Watts Gallery and Chapel, at Compton, near Guildford. (Take British Rail to Guildford.) This memorial to G.F. Watts – the glorious decorated chapel was designed by his artist wife, Mary Seton Watts – has been undergoing renovation/restoration and is slated to re-open in the summer of 2011.