On the edge of the city of Salisbury is one of England’s greatest country houses, the home of the Herbert family for almost five centuries. Wilton is one of those fabled British Country Houses which almost defy description. Should one concentrate on the architecture, which includes Tudor, Elizabethan, Palladian, and Regency examples? The interior, of amazing variety and stellar quality? The gardens? The collection of old master artworks? Or, how about the many stories of the history of the Herbert family, which is currently represented by William Alexander Sidney Herbert, 18th Earl of Pembroke, his Countess and their four children?

The top photo shows the North Front, dating from the Tudor era, the current public entrance to the house. Immediately above is the South Front, the wing of the house probably designed by Architect Indigo Jones in the Palladian style in the 17th century. This area contains the sumptuous state rooms.

Above, the East Front, opening into the public lawns and gardens, dating before the 16th century. This was the original entrance to the house. You can see that even today, restoration work is necessary.

The West Front and its garden are the private areas of the 18th Earl of Pembroke, his wife and four children. Below, the official portrait of William Herbert, the 18th Earl of Pembroke, and his dog painted by artist Adrian Gottlieb. ‘Will’ is the latest of the long line of owners belonging to the Herbert family,

I am sorry to report that no photography is allowed in the house so in these posts, I will be mixing ‘borrowed’ photos, of which there are many on the web, with my own pictures. First, let’s look at the exterior and the gardens. Below, an aerial shot of the house with the south façade at the left.

Below, from the central cloisters courtyard, looking east at the inside of the East Front. The original house was built on the site of an 8th-century priory. After Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries, the site was ceded to Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke (of the new creation) in 1544. He constructed a house in the quadrangular style which through many remodelings, remains today with a central open courtyard.

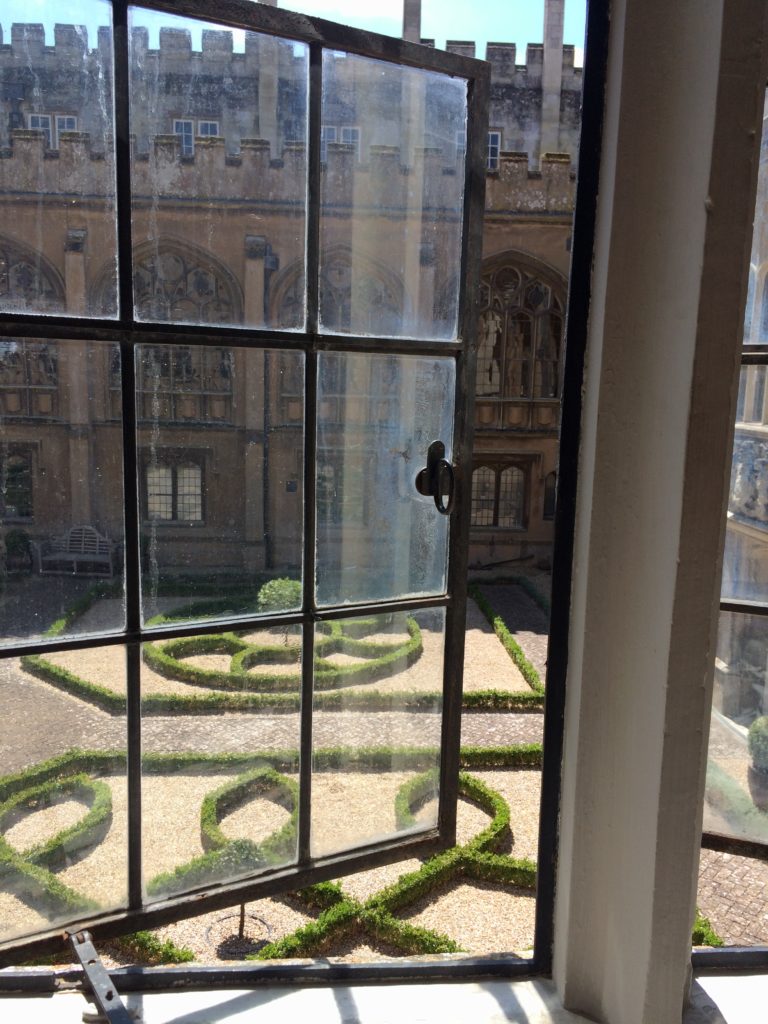

Below, peeking out from inside the cloisters, re-built by James Wyatt in 1801.

Inside the Cloisters, you will find a collection of statuary, including rare classical antiques collected by the Earls of Pembroke.

Today, visitors enter through another courtyard facing the North Front, past the fountain and a grove of trees among the patterned plantings.

Behind us was the great gate, often a symbol of Wilton House.

Leaving the interior for another post, let’s look at some of the gardens. I am particularly fond of Palladian Bridges – why I cannot imagine, but I find them charming. Below, the Wilton Palladian Bridge, constructed in 1737 by the 9th Earl of Pembroke, known as the “Architect Earl” and his assistant Roger Morris. It was designed to bridge the River Nadder in the style of the Italian architect Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). It has been copied at least three times, at Stowe and at Prior Park near Bath in England and at Tsarskoe Selo near St. Petersburg, Russia.

The inspiration for the Palladian Bridge is reputedly an unbuilt design for Venice’s Rialto Bridge, drawn by Andrea Palladio about 1570, pictured below in a Capriccio by Canaletto, 1742.

The river Nadder is a chalk stream known for its trout flyfishing.

Below, the charming Japanese Garden, also known as the Water Garden, with its red bridges and reflecting pools, was designed by Henry Herbert, 17th Earl of Pembroke, who died in 2003.

In Part Two, we will look at the magnificent interiors of Wilton House.